Plant-based food traditions run deep in the 23rd state, and it shows in the just published “Maine Bicentennial Community Cookbook.”

Billed as “200 Recipes Celebrating Maine’s Culinary Past, Present & Future,” the book was compiled and edited by Margaret Hathaway and Karl Schatz, the owners of Ten Apple Farm in Gray. The printing was crowdfunded and the recipes crowdsourced. The price: $20.20. While the cookbook includes many meat- and seafood-based recipes, it also reveals Maine’s ever-present vegetarian flavor.

Hathaway was raised in a vegetarian home in Wichita, Kansas, and never tasted meat until she lived in Africa during her 20s. She said she’s gratified by “how many of the recipes are vegetarian,” adding “some have been developed specifically to be meatless, but the bulk are simply reminders of how thrifty New Englanders stretched their larders and food budgets.”

One such budget-friendly, naturally vegan dish is the ployes recipe from Norma Dionne of Van Buren. Dionne grew up eating ployes with “stew and baked beans.” These days, Maine vegans and others are apt to eat ployes as breakfast pancakes, with maple syrup and other sweet toppings.

The Bicentennial cookbook devotes a chapter to baked beans. While four of the baked bean recipes add anywhere from several strips of bacon to 1 1/2 pounds of salt pork, the fifth is vegan. That all-vegetarian recipe features yellow-eye beans and comes from Martha Hadley of Fort Fairfield, who grew up eating these baked beans every Saturday night, with leftovers for Sunday brunch.

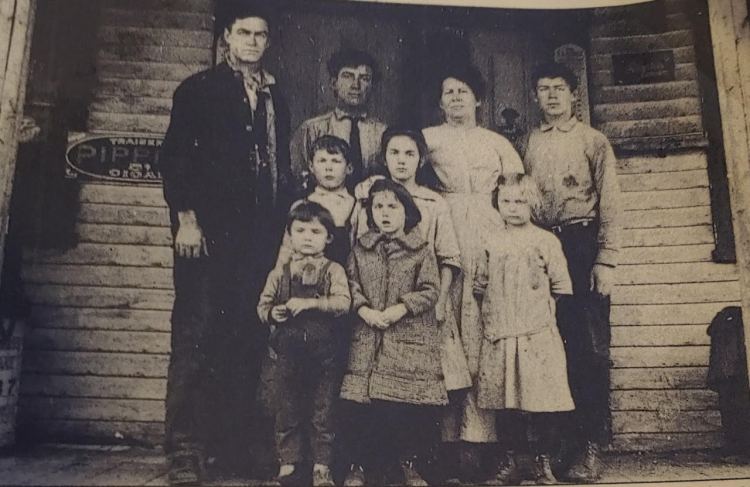

Even meat-seasoned beans, when eaten with ployes or cornbread, become a low-impact, mostly plant-based meal, and have long been a mainstay in both vegetarian and non-vegetarian homes. Brenda Bourgoine of Caribou shared a photograph of a “floating cook shack” surrounded by a logging crew it fed in the 1940s on the St. John River. Bourgoine noted the menu was always “baked beans, which were served every meal, with bread or pancakes.”

The current trend away from cow-based dairy products can be spotted in the cookbook’s brown bread recipe that comes from Krista Marvel, chair of the culinary arts department at York County Community College. The recipe, which can be traced back to colonial times, calls for the usual wheat, rye, cornmeal and molasses, while listing “coconut, hemp, almond or soy” as potential substitutes for the 1 cup milk.

Other notable vegetarian recipes come from Jo Cameron of Edgecomb, who contributed her naturally vegan mujuddarah recipe; Elizabeth Stanton of Portland, who gave her recipe for lentil burgers; and Frances Harlow Clukey of Bangor, who submitted a vegetarian breakfast recipe for sea moss farina made with seaweed, milk and honey. Astronaut Jessica Meir was in space when the call went out for recipes, so her mother, Ulla Meir of Caribou, shared her daughter’s favorite vegetarian chickpea salad, made with cherry tomatoes, cucumbers and feta. Even my pumpkin seed croquettes with shiitake mushroom gravy made it into the book.

The book contains at least one meat dish I suspect harbors secret vegetarian undertones. The haunting recipe called lunchtime gloop shared by horror master Stephen King calls for “2 cans Franco American Spaghetti (without meatballs)” and “1 pound cheap, greasy hamburger.” King advises cooks not to drain the grease and invites them to burn the mixture “if you want.” He recommends serving it with “buttered Wonder Bread.”

Knowing the care King takes with words, I wonder if the scary meat-based atmosphere is intentional? King admits he only makes this frightening meal when his wife, Tabitha King, isn’t home since “she doesn’t even like to look at it.” Also consider that in the 1990s King’s daughter Naomi King owned a vegetarian restaurant, Tabitha Jean’s, on Free Street in Portland.

Unsurprisingly, almost all of the dessert recipes are vegetarian, with a handful of vegan treats including potato fudge contributed by Rosalie Colby of Hiram; a vegan lemon raspberry poppyseed layered cake from Betsy Harding of South Portland; a recipe for Arlene’s World War II spice cupcakes submitted by Erik Nielsen of Portland; the Danish raspberry almond bars from Debra Wallace in Cumberland; and the flax seed candy originally published in an 1882 community cookbook created by the Ladies of Bangor.

The attractive bicentennial cookbook will interest both historians and cooks, as it marks Maine’s 1820 independence from Massachusetts not only with recipes but with stories. There are essays by Maine apple expert John Bunker and executive director of the Cumberland County Food Security Council Jim Hanna. Hanna’s essay, “Ending Hunger in Maine by 2030,” mentions the state’s most famous vegetarians, writing that ‘the way life should be’ state brand is “grounded in a back-to-nature movement articulated in Scott and Helen Nearings’ book ‘Living the Good Life.'” We can only live the good life, Hanna asserts, when everyone has enough to eat.

The website maine200cookbook.com includes a downloadable index of all the vegetarian recipes in the book. In addition, the website offers recipe cards for sale, featuring dishes – some vegan and vegetarian – that didn’t make it into the cookbook.

Hathaway, who calls vegetarian classic “The Moosewood Cookbook” her comfort food, thought at the outset of this community cookbook project that “people would send us a lot of boiled dinner and seafood recipes. But I was surprised by how many recipes people sent us were completely plant-based and vegetarian. It made me rethink my perceptions of what (Mainers) eat. It makes me see things through a different lens.”

Avery Yale Kamila is a food writer who lives in Portland. She can be reached:

avery.kamila@gmail.com

Twitter: AveryYaleKamila

Send questions/comments to the editors.