Jackie Ingraham grew up surrounded by land, animals and family.

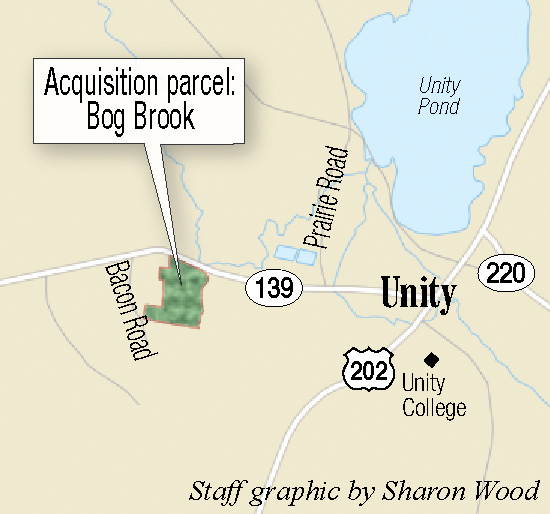

She lived in a house with her sister, parents and grandparents on 150 acres of land in Unity along where Route 139 west now runs.

The land is now owned by the Sebasticook Regional Land Trust, which bought it for $54,000 in March. The acquisition will create a 1,500-acre corridor of conserved land for hikers, hunters and students.

“It’s about keeping it open and available for the community to use,” said Jennifer Irving, executive director of the land trust.

When Ingraham’s mother died, the sisters wanted a way to honor their family, Irving said. They decided to sell the acreage to the land trust so it would become “community land” that would never be developed.

Her grandparents and parents would love the idea of preserving the land with the land trust and opening it up to the community, Ingraham said.

She fondly remembers a childhood spent mostly outdoors. The family had a “menagerie farm,” she said. Her grandfather had a cow, a workhorse, riding horses, chickens, goats and sheep. Her grandmother also raised German shepherd puppies to sell.

“It was like a sustainable agriculture time, where you raised your own meat,” Ingraham said in a phone interview Thursday.

She rode the horses daily with her sister, Linda Berry. In the winter, they would come home from school, change their clothes and head out to skate one of the two frozen ponds on the property.

“We thought we were going to go to the Olympics, of course,” Ingraham said.

The sisters knew the limitations of the property though, she said. Within the land is a bog, Bog Brook, so they weren’t allowed past a certain pine tree.

“There’s no bottom out there, as my dad would say,” Ingraham said.

There was also occasional flooding. Ingraham remembers having to stay home from school multiple times because what they called “the river” would flood up to their house, so the school bus couldn’t reach them.

FOR PEOPLE AND WILDLIFE

The land from the sisters connects Fowler Bog to Bog Brook, where there is bass fishing. Across Route 139 is another 700 acres the Land Trust owns, Moulton’s Mill. The new land is part of the Unity wetlands, which is an important environment to maintain, Irving said.

The Land Trust bought the 150 acres with a combination of federal money from the Fish and Wildlife Service and state money from the Nature Conservancy. The federal grant required some land to be donated, so the Bessey family donated 40 acres connected to Fowler Bog.

A trail that was initially overgrown brush and littered with 40 years of illegally dumped tires goes all the way through the Rines’ land to Fowler Bog. The trail was built on an esker, a road that goes along a ridge, with dropoffs on either side. The sides now have vernal pools with frogs, salamanders and turtles, Irving said.

The whole area has a lot of biodiversity, Irving said, and some endangered or threatened species of animals and plants, like wood turtles, silver maples and freshwater mussels. Beavers, moose, bobcats and a variety of birds also live there.

The land is available for people to hike, bird watch, hunt or fish. Irving said in May the land conservation will create new outdoor recreation opportunities in the Twenty-five Mile Stream region in northwest Unity.

“On its journey from Unity Pond to the Sebasticook River, the stream travels through one of central Maine’s largest remaining blocks of undeveloped habitat,” Irving said at the time. “That means it’s home to critters that need lots of space, like moose, bear, bobcat, fisher and woodland hawks. It’s also home to less common animals and plants: wood turtles, wild garlic and bur oak, to name a few.

“That’s why this acquisition is so important: It provides adequate space for wildlife, creates new spaces for recreation, and when added to our other, adjoining conservation acquisitions, provides a lasting example of Sebasticook Regional Land Trust’s long dedication to habitat protection.”

KIDS AND NATURE

The land trust also works with schools for educational trips, as well as with afterschool programs. Unity College works with the land trust as well.

“It’s really important that we get our kids outside and connecting with nature,” she said last week. If they understand why nature is important, then the land will truly be conserved “forever.”

The land trust held a birding walk for International Bird Day in May, and members of the trust plan to hold other events such as wildflower walks or tracking frogs. The organization also plans to create walking trails and build observation platforms that will reach out onto the bog.

A crew of about 30 committed volunteers helps out, and they see more than 200 volunteers each year, Irving said. They hold cleanups to dispose of items that are illegally dumped, like tires, which Irving said is a problem.

Irving said they’ve acquired 4,000 acres in the 12 years since they started.

“That’s because we’re in a community that is so supportive,” she said.

Ingraham Thursday said her family took advantage of the nature around them on the land in Unity, hunting and gardening instead of going to the store each week. They even chopped down their Christmas tree on their property each year.

The two sisters would play outside in the summer, since they didn’t have a television until Ingraham was 12.

Her father, Vinal Rines, was a registered Maine Guide, so he could help them find plants and flowers. Her mother, Georgia Rines, stayed at home with her children and taught Sunday school. Both parents had a lot of respect for wildlife.

In a news release announcing the land acquisition in May, Ingraham said, “For this land to be used for something like this – for wildlife – that would have made (my parents) very happy.”

Thursday she said, though the family never had much money, “I thought we had everything when we were kids.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.