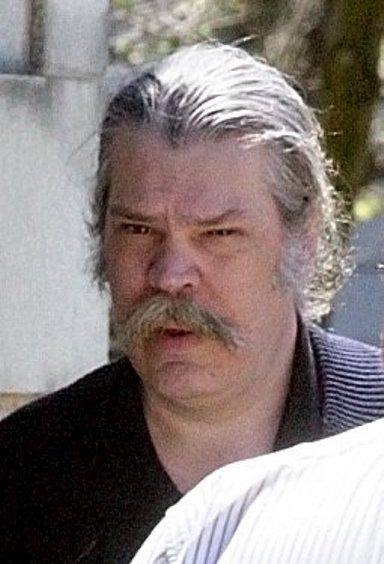

AUGUSTA — Mark Bechard, who was committed to a state psychiatric hospital after killing two nuns and severely injuring two others in Waterville in 1996, is doing well mentally, could benefit from more independence, and is ready to move from a group home to a supervised apartment in Augusta, experts testified in a court hearing Tuesday.

However a state prosecutor and the leader of the State Forensic Service said the turnover of staff on the state clinical team charged with overseeing his treatment is so high that leadership of the team is in “disarray,” and some of those workers might not know Bechard well enough to recognize a deterioration of his mental health status.

Justice Robert Mullen, presiding over a court hearing to consider Bechard’s petition seeking to be allowed to move from his currently approved residence in a group home on Glenridge Drive to a 10-unit apartment building on Commercial Street in downtown Augusta supervised by at least two people at all times, said he’ll rule on the request within two weeks.

Ann LeBlanc, director of the State Forensic Services, which evaluates the mental health status of people committed to the state, and who has known Bechard since 1996, said he is currently functioning better than she has ever seen him, has been reliable in taking his anti-psychosis medications, has done nothing that would cause any concern to community members, and would benefit from moving out of a group home and into a quieter, more independent apartment in a supervised building.

But she expressed concerns that turnover of staff, particularly in leadership positions, on his clinical treatment team is so frequent “the team appears to be in disarray.” She said Bechard has had at least three different psychiatric care providers since she last evaluated him in January, didn’t know who his case manager was at that time, doesn’t have a nurse practitioner assigned to his care team, and is going to get a new intensive case manager and new psychiatrist later this year because the men currently in those roles are leaving. She said the people coming into those roles may very well be highly talented, caring professionals but don’t know Bechard well and may not recognize it if his condition were to deteriorate. And due to the high turnover, those caregivers may not be able to provide the integration of services Bechard needs to be successful. She said he can be suspicious of new people, and it takes time for him to trust new mental health caregivers.

She noted her concern is not that Bechard would “become psychotic and injure someone,” but that his condition could deteriorate gradually and his clinical treatment team with Riverview Outpatient Services might not know him well enough to recognize it promptly and “he could lose ground, psychologically, and have to go back into the hospital.”

LeBlanc suggested waiting five months, as Bechard gets used to his current clinical team, before allowing him to move.

Harold Hainke, Bechard’s attorney, argued Bechard’s mental health is at a high-functioning level, his treatment team is well-informed, he would have contact with staff and service providers so regularly that a deterioration of his condition would be noticed, he does have regular interaction with support staff who have known him for many years, and he would benefit from the move.

Hainke said Bechard can be introverted and prefers peace and quite, something that can be hard to come by in the group home where he is living now.

“It may be more risky for Mr. Bechard to stay where he is now than move,” Hainke said.

Hainke said there is no way of guaranteeing in five months that there won’t be other changes to the staff involved in overseeing Bechard’s care. He said it would be unfair and a hindrance to his therapy to make him remain in the group home, waiting for staff to be stabilized.

Mullen said he couldn’t remember the last time he went through mental health evaluation reports where all the reports were so consistently positive about a patient as were the reports submitted about Bechard by LeBlanc and state mental health workers.

Bechard, 57, also requested as part of the petition that he be allowed a three-hour block of unsupervised time in the community per day. Bechard currently is allowed two, one-hour blocks of unsupervised time in the community per day.

Elizabeth Cravey, a registered nurse who will take over as Bechard’s intensive case manager soon after his current case manager retires, and who has worked with Bechard before, said he often spends his unsupervised time taking long walks. She said upping that allowed unsupervised time to three hours at a time would be beneficial to him and allow him to take part in activities such as going to a movie or taking in a local jazz brunch he enjoys attending, which take more than one hour.

Greg Kaczenski, Bechard’s current psychiatrist with Riverview Outpatient Services, said Bechard would still be required to check in every hour, and the risk involved in increasing his unsupervised time “would be quite low.”

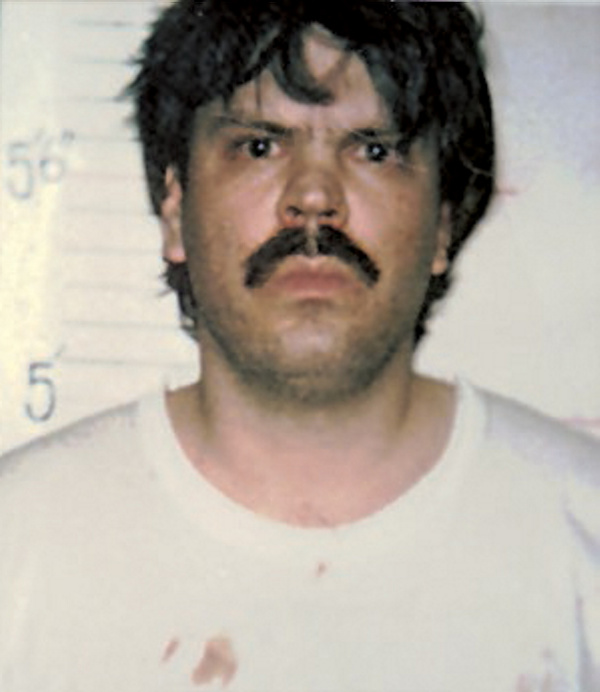

Authorities said Bechard, 37 at the time, was suffering a psychotic episode when he entered through the chapel at the Servants of the Blessed Sacrament convent in Waterville on Jan. 27, 1996. He attacked four nuns, killing Mother Superior Edna Mary Cardozo and Sister Marie Julien Fortin.

Sister Patricia Ann Keane survived the attack but died later from her injuries. Sister Mary Anna DiGiacomo, who was paralyzed on her right side, died in 2006.

Send questions/comments to the editors.