This article is largely about small, beautiful works. I didn’t plan it that way; it just happened.

I begin with “Assembled Thoughts” at Whitney Art Works. Billed as “a showcase of two witty, bizarre and entirely self-sufficient/contained/referential worlds,” it introduces work by Ethan Hayes-Chute and Yeshe Parks.

In the case of Hayes-Chute, we are drawn into tiny hermetic realms, detached places from which people have decamped leaving the fabric of their civilizations untouched. The occupants picked up their pots and pans, swept the floors and left, taking the sky with them. The structures are abandoned to a silence so exclusive that you can feel it with your skin.

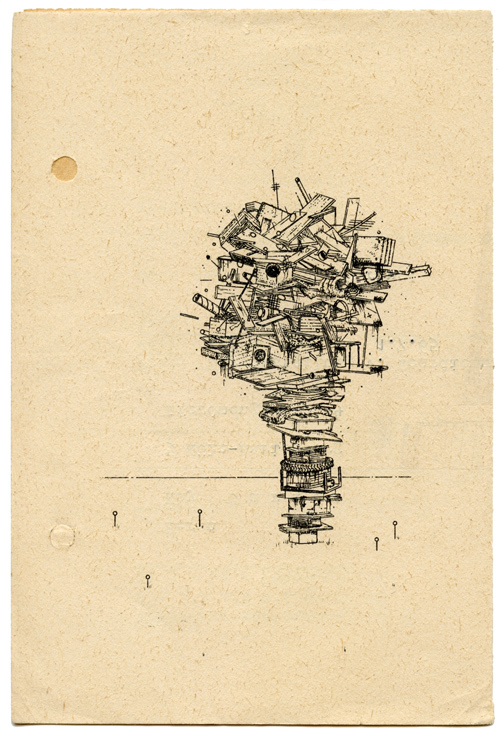

Hayes-Chute gives us an account of that absence — that silence — and of the structures, shanties really, marooned in it. It is accomplished on tiny sheets of paper sometimes in hard graphite, sometimes in ink, but always with a mania for microscopic detail. The artist snared the sheets with their aggravations of age from a dumpster and, with infinite application, used them to create fantasies that seem spontaneous. The contrasts among the precision of execution, the wretchedness of the paper, the unsubstantiality of the forms and their spontaneity make these miniscule works irresistible.

If all of this isn’t clear, perhaps you can remember “Hermitage,” the structure erected by the artist in the lobby of the Portland Museum of Art for the 2009 Biennial. The fantasy in these drawings replaces the cleverness that was charming in the three-dimensional structure, but the basic structural forms are similar.

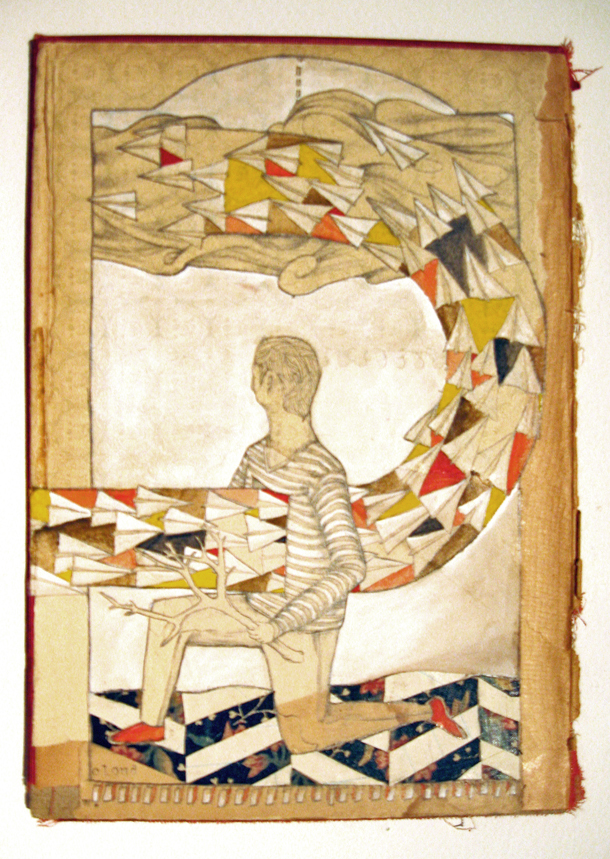

Parks is also a veteran of the Biennial. In this case it was 2007, but here, as a maker of collages, drawings and various works in mixed media, he is a social commenter and philosopher. Excluding an occasional touch of whimsy, he inhabits a gloomier world than we are usually asked to face. There is a sense of anxiety, of struggle, of moral issues in his work. It has been a long time since a Maine artist has taken up such matters, and I find the effort arresting.

Better stated, the work seeks a level of social intensity that has been generally avoided in recent decades, and thus makes a contribution to the purposes of art. I hasten to point out that several of Parks’ abstract collages are classic in their tradition and quite wonderful, and his drawing “two-hundred and sixty something self-portraits” (sic) is hilarious.

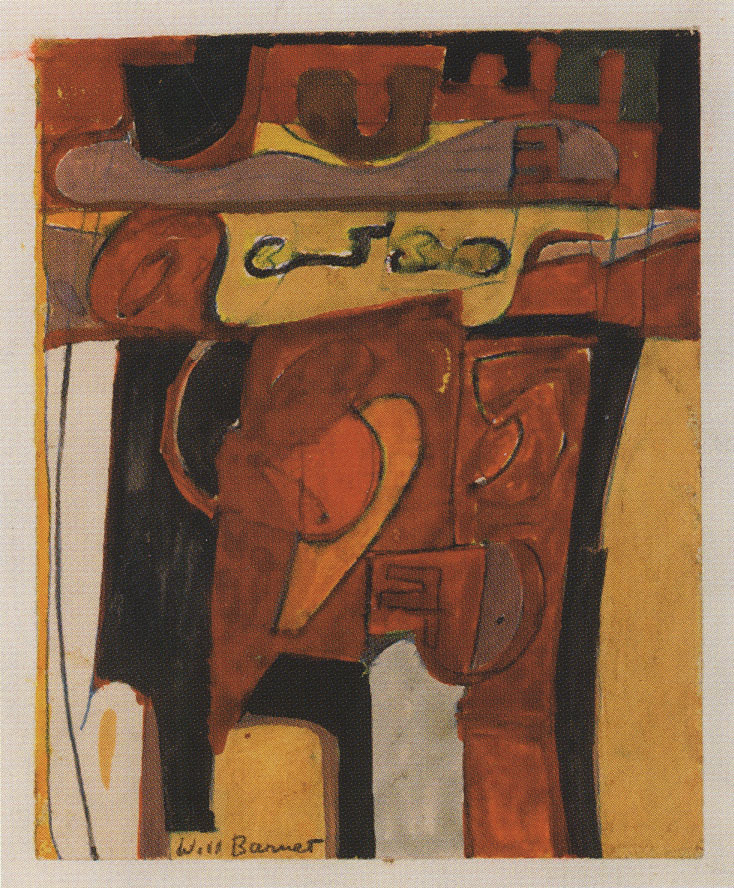

My fascination with the small — at least to the not-large — extends to portions of “Will Barnet, Master Printmaker: Selections From Five Decades” at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art in Rockport. Barnet is a universally admired artist, and his images of elegiac women rendered in solemn tones have iconic status in American art. Versions of these, in print form, appear in this show, but my attention was kidnapped by a series of small drawings and related prints from the late 1950s and early 1960s.

I was not familiar with Barnet’s work of the period and was not prepared for its immediacy, its directness and its warm, rhythmic nature. The small drawings and watercolors that precede the prints of the time are jewels of abstraction. They are a fusion of flattened cubist forms, and are unforgettable.

Some, such as “Big Duluth (Study)” (1959), have strong typographic suggestions. Others, as in “Study for Big Black” (1959), have figurative and even architectural allusions, and one among them, “Untitled II” (1957-60), is a synthesis of abstract concepts so remarkable as to become a fresh and vigorous aesthetic philosophy. I was overwhelmed by it.

This portion of the show is accompanied by several of the ensuing prints, including the color woodcut “Big Grey” (1962) and the magnificent color etching “Dark Image” (1960). This is a rare opportunity to get close to the germ plasm of the golden age of American painting.

CMCA is also exhibiting paintings and drawings by Dozier Bell. Accomplished over the last decade, they include several of her small charcoals on mylar and a number of her larger works in acrylic.

In the small drawings, Bell flirts with the prosaic when she turns to the skylines of urban Europe, but in the main, they remain intense in their skepticism about the repentance of the homicidal among the European community of nations.

She moves from this a bit in “Cloud” (2009), an onlay that provides a bombardier’s glimpse of a bit of land and a stream. “Confluence” (2010), a large acrylic, defines the term “atmospheric.” Through a wan sun that edges past a line of dark amorphous clouds, a watery landscape presses for recognition. The result of its efforts may be sinister to it.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 45 years. He can be contacted at: pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.