PHIPPSBURG — John Marin painted here.

On this very spot, on this ledge of granite that emerges from a deep-green forest of spruce trees and slopes slowly down into the sea, Marin wandered about almost 100 years ago.

Marin, an artist who led America to abstraction, came to Maine for the first time in 1914, and spent the better part of August and September holed up in a tiny shack on the southern end of a small island in Casco Bay, a few feet from high tide.

No doubt, he found what he was looking for — the need to be alone, to rusticate and to live an existential life in a two-room cabin without any of the conveniences of modern life, even by the standards of the early 20th century.

It was his first Maine experience, and he obviously liked it. He would return nearly every summer for the rest of his life, eventually settling far up the coast in Cape Split at Addison.

Phippsburg was his first stop.

He wrote to his New York dealer about the wonder of his location. He described it as a “fierce, relentless, cruel, beautiful, fascinating, hellish and all the ish’s place. At high tide our little shack is 15 feet from the water on a ledge of rock running down into the water.”

At the time, Marin was searching for his artistic voice. As filmmaker Michael Maglaras made so clear in his recent documentary “John Marin: Let the Paint Be Paint,” Marin became the painter we know him to be because of his experiences in Maine.

Maine gave him purpose, and set him on the path of profound influence. Without Maine, Marin would be just another New York painter. Because of Maine, he became inarguably one of the most important artists in American history, bridging realism and abstraction in a way that no one did before and few have done as well since.

We see evidence of Marin’s accomplishment during that first trip to Maine in the current exhibition at the Portland Museum of Art, “American Moderns: Masterworks on Paper from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.” It’s on view through Sept. 12.

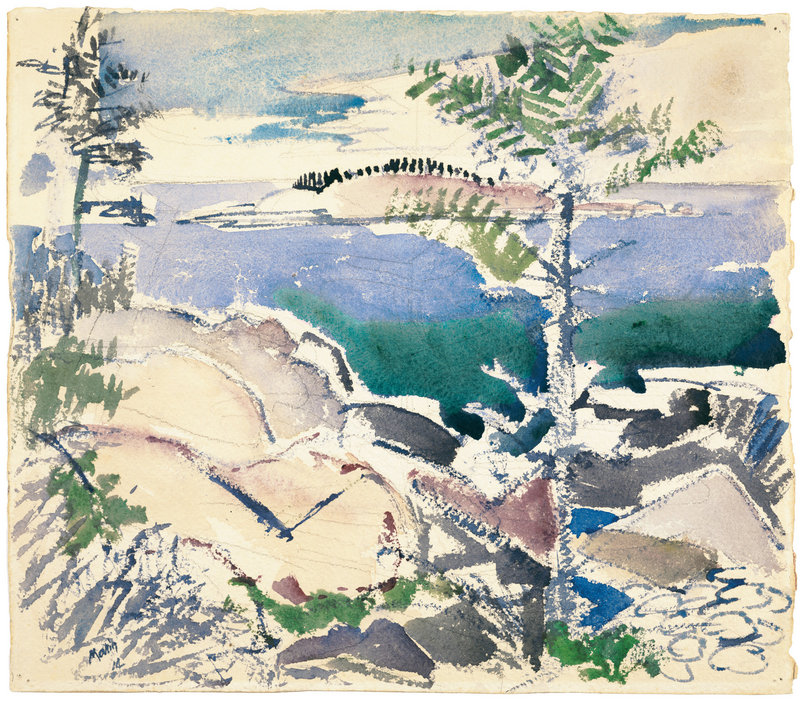

The show includes six Marins, and the best of the bunch is from that first visit in 1914. It’s called “Big Wood Island,” and Marin painted it on the rocks near the cabin where he shacked up. He offers a resplendent view of Wood Island in the distance, looking from one island out to another.

The rock where he made this simple watercolor is a spot I am lucky to know well. It so happens, through chance and circumstance, that my grandparents purchased this land a few years after Marin stayed here. My grandfather operated a pharmacy in a Boston suburb, and had enough success in life that he was able to afford summer property on the coast of Maine.

For years, my grandmother regaled our family with stories about Marin and the time he spent on the island. As far as I know, my grandparents never met or knew Marin — he had moved up the coast by the time they acquired this place.

Nonetheless, her stories had the air of authority, and I always presumed them to be true. But until I walked into the gallery at the PMA and saw Marin’s “Big Wood Island” for myself, I lacked hard evidence. This painting proved not only that Marin was here, but that he stayed long enough to get to know the place.

Seeing this painting affirmed that whatever connectedness I have felt with Marin over the years was not imagined, but was an actual, tangible thing. On these very rocks where Marin made this painting, my brothers and I have spread the ashes of our parents, courted our mates and — we hope — instilled lasting values in our offspring that will keep this place as unspoiled as it was nearly 100 years ago, when Marin stopped here ever so briefly on his own personal journey.

Over time, the cabin where Marin laid his head has sustained the indignity of decay, thanks to a series of nor’easters, hurricanes and relentless sea-driven winds. It’s never been more than a simple shack perched on the edge of a rugged place. These days, the walls are caving in, the floor is rotted through and poison ivy rings the perimeter. Any year now, the chimney will fall into the roof and become a rubble of bricks.

But this place — this nub of land where once an artist spent a few weeks exploring his muse — will stand forever until a power greater than any of us can imagine decides otherwise.

That he left his mark on paper as a record of his time was his gift to all of us.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at: bkeyes@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.