Judith Magyar Isaacson arrived at Auschwitz at 19, confused and afraid, torn away from her quiet childhood in Hungary and her dreams of studying at the Sorbonne.

Stripped of clothes and her head shaved, she was fed soup made of sticks and leaves, and later was forced to work in an underground munitions factory in Hessisch Lichtenau, Germany.

“One didn’t think one could survive,” she said during an oral history interview archived by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “The first few days at Auschwitz, it was like being drugged. I didn’t know where I was. I couldn’t recognize my mother or aunt because they were bald. … It was too much to bear.”

But she did find a way, surviving the atrocities at Auschwitz, the Nazi concentration camp where 1.1 million people died, before going on to live a joyful and successful life in the United States, and carving out a notable career in education in Maine.

Isaacson, who delivered many lectures about her experiences and authored the best-selling book “Seed of Sarah: Memoirs of a Survivor,” died Tuesday. She was 90.

“She wanted everyone to know the story in the hope that if people could remember such evil, they would not allow it to happen again,” said her daughter, Ilona Bell. “It was her mission. She was driven to tell her story.”

Isaacson – called Jutka by those closest to her – was born in 1925 in Hungary, the only child in a close extended family. Her dreams of writing poetry and studying in Paris were dashed during the German occupation when her family was forced to move to a ghetto, stripped of its belongings and ultimately split up and sent to concentration camps. She arrived at Auschwitz two days after her 19th birthday.

There, surrounded by thousands of naked prisoners and trying desperately to stay with her mother and aunt, Isaacson defied an order from Dr. Josef Mengele, the notorious German doctor who decided which prisoners would be sent to the gas chambers and which would survive one more day. A guard told her she’d be shot if she tried to stay with her mother.

“I said, ‘I don’t care. It’s better to be shot now than to be separated,’ ” Isaacson recalled in her 1993 oral history interview. “I expected them to shoot me in the back. I still remember that feeling, to expect a bullet to come. … That is how we survived.”

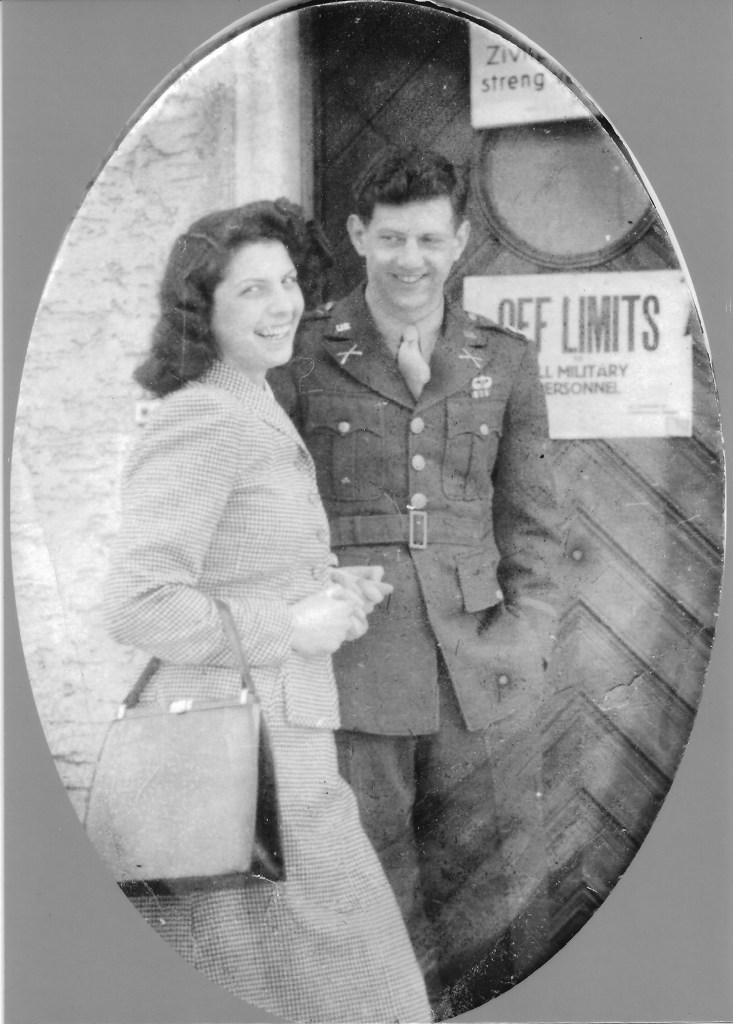

After a month at Auschwitz and nearly a year working at an underground munitions factory in Hessisch Lichtenau, Isaacson, her mother and aunt were liberated in Leipzig by American forces in April 1945. A month later, she met Irving Isaacson, a Lewiston native serving as a captain in the U.S. Army Office of Strategic Services. They were married within months.

The Isaacsons returned to Maine, where they settled in Auburn and raised three children. She is survived by her husband, who is 100, and they would have celebrated their 70th wedding anniversary Dec. 24.

“They had a fairytale romance. Everyone who met them said they were an extraordinary couple,” Bell said. “They were a great source of comfort and support for each other. He just said, ‘My heart is breaking. I’m losing half my life.’ ”

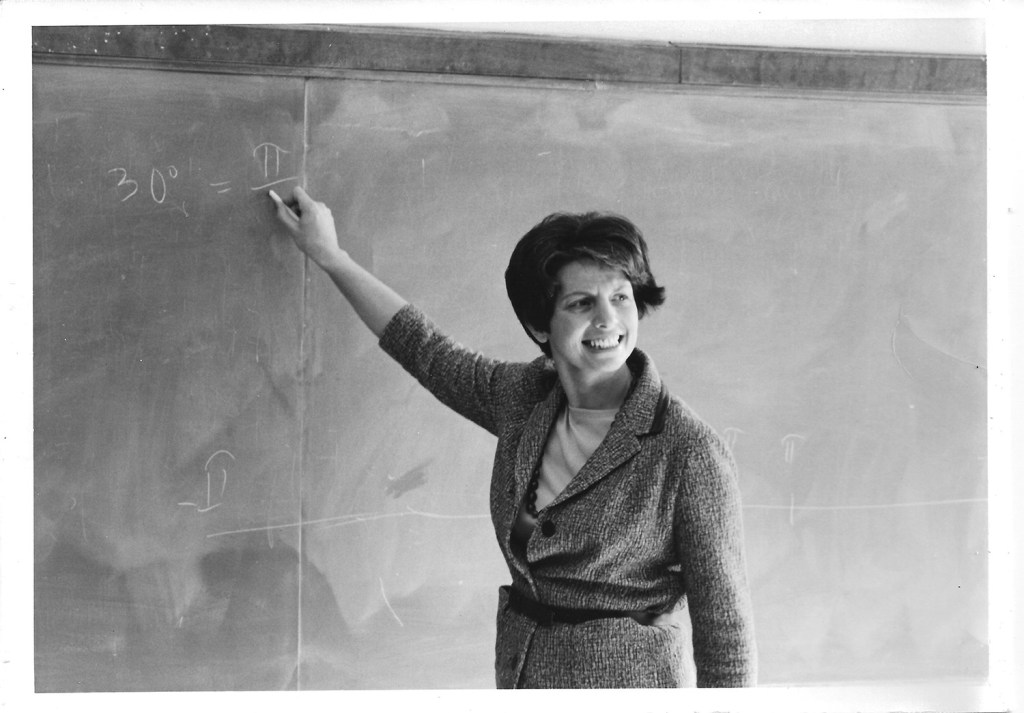

When the Isaacsons’ youngest son started kindergarten, Judith Isaacson threw herself into her education, earning a degree in mathematics from Bates College in 1965. Ten years later, she was one of the first women to earn a master’s degree from Bowdoin College. She taught math at Lewiston High School, then became the first computer science teacher at Bates. Her distinguished career in education continued at Bates, where she was named the college’s first dean of students.

During those years, Isaacson openly shared her experiences about the Holocaust. After a talk at Bowdoin, a student asked her how she could smile so openly after all the horror she had seen. She started writing her book that night.

“She bore witness, but she bore witness with a very unique ability to give people the confidence that you can face terrible adversity, but you can come out and still love life and be happy,” Bell said.

Steve Hochstadt, a Holocaust scholar who befriended Isaacson when he taught at Bates, said Isaacson was one of the first female memoirists of the Holocaust to talk openly about how it affected women.

“Judith Isaacson, because of her book, has gone way beyond the bounds of Auburn, Maine, to become a famous person who people will continue to read about for a long time,” he said. “She was an extraordinarily joyous person who could tell you about very sad things that happened to her, her relatives and her friends, but who was able to retain joy in life.”

Katalin Vecsey – a senior lecturer at Bates who considered Isaacson her “Hungarian mother in the United States” – said Isaacson began her book with the quote, “All who live rejoice, rejoice.”

“I think that totally sums up her life,” she said. “She really was so grateful to be alive and she shared that joy with everybody.”

Though telling her story of survival was often emotionally draining, Isaacson loved connecting with young people and helping them understand her experience, said her friend, Joan Macri.

“In her presence, you were just happy,” Macri said. “She told me she woke up every morning and thanked the good Lord for every bone and muscle that didn’t hurt. I think that said it all about her. She looked at what was good, not what was bad.”

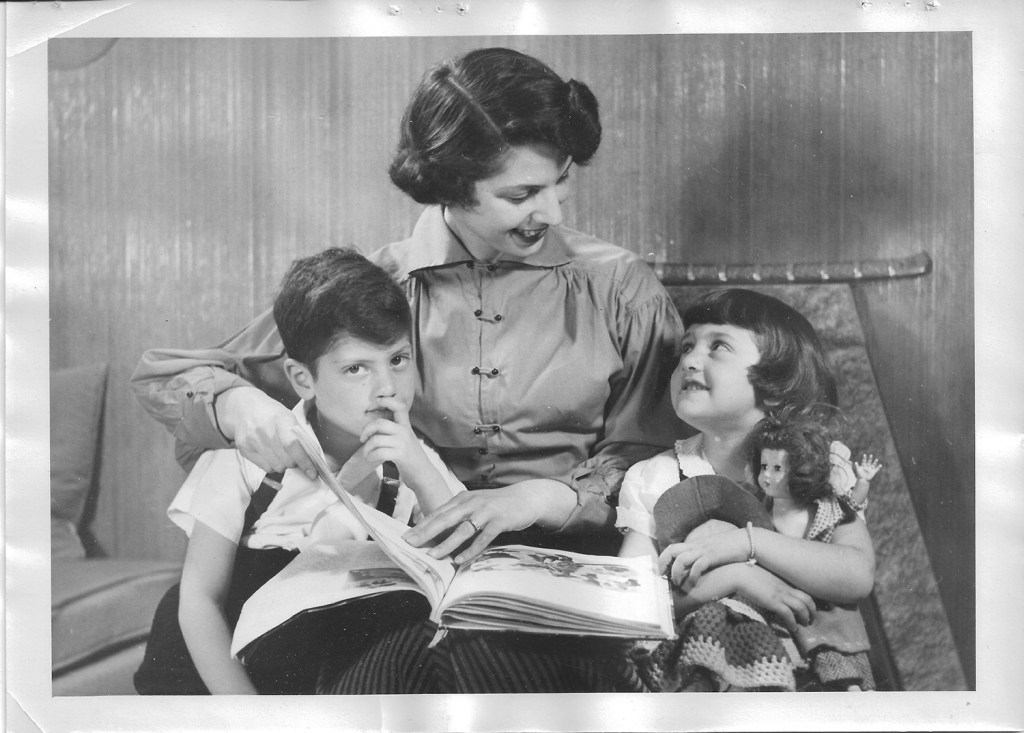

While many people will remember Isaacson for her contributions to public life and sharing her extraordinary story, members of her family – besides her husband, she is survived by their three children and their spouses, eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren – said they also will treasure memories of the happy and cozy home she created for them. They describe her exquisite Hungarian dishes, her zest for life and her enthusiasm for playing with her grandchildren. Before she died, Isaacson was able to meet her first great-grandchild.

“She was as comfortable getting down on the floor and playing with little kids as she was talking very freely and openly about her childhood growing up in Hungary,” said her granddaughter, Kaitlin Bell Barnett. “She was a wonderful storyteller. She lived history and she brought it alive for people.”

Services will be held at Temple Shalom in Auburn at 11 a.m. Friday.

Send questions/comments to the editors.