America in many ways has relegated Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. too thoroughly into history. His words were poetry, delivered practically in song. His remembrance day is in bleakest January, the streets named for him often found in forgotten corners of our cities.

Relegated by white people, anyway. Katori Hall’s “The Mountaintop,” a two-person play deftly executed at Portland Stage through Nov. 22, goes far in rectifying that. It imagines King the stormy evening hours after he gives his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, and hours before he is assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. “The Mountaintop” is dense and sometimes difficult, deep and sometimes funny. At an hour and half, without intermission, it’s also captivating, and it is a gift.

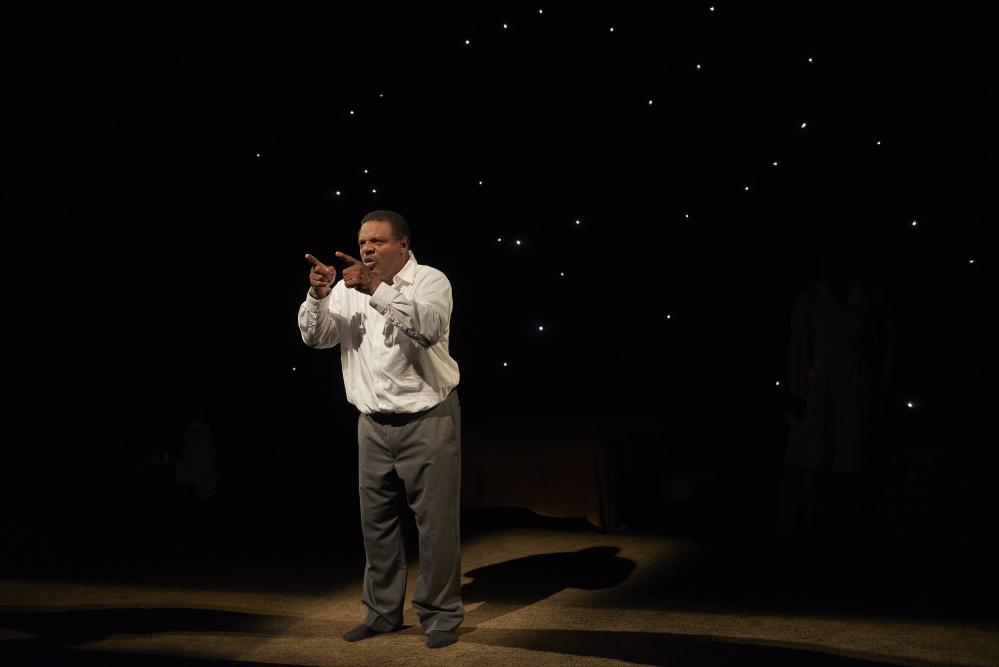

Hall’s King (Harvy Blanks) is not the striking man many of us only know from black and white film or Kodachrome portraits. He’s a weary, smelly-footed, cigarette-jonesing human being, with doubts, temptations and plenty to say outside his stirring speeches. It’s worth noting that Blanks and director Charles Weldon have personal memories of that time. Perhaps that’s why Weldon so thoroughly takes us there too.

But if King’s pulpit has become something of a pedestal, this play brings him to us a lowered, frustrated man. We meet him as he enters his room at the Lorraine, remarkable to us mostly because of its sad, violent moment. The set is rendered faithfully to that actual room, 306, where King stayed so often with his friend Rev. Ralph Abernathy that it was jokingly referred to as “the King-Abernathy Suite.” There are touches, like the rotary-dial phone, that tell us we’re in 1969. But, like King that night, we’re confined to that modest motel space, and in “The Mountaintop,” it is intimate quarters indeed.

At first we’re just with King himself, until the wisecracking and wise maid, Camae (Kim Staunton), joins him, to challenge him, share time and ideas with him, and give him coffee and cigarettes. We feel every thunderbolt, as lightning flashes on the rainy balcony just outside, and see first-hand how terrifying they were to Dr. King, who was routinely suffering death threats by then.

The two have quite an evening, and Blanks and Staunton give physical, dynamic performances. Blanks brings us King the mortal man, but maintains the preacher’s confident, intellectual high-mindedness. Their talk is flirty and genuine, at times fraught with class differences and wildly differing notions of righteousness. King fervently believed in America. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, along with the Christian Bible, could be depended on, he thought, to help correct the grievous mistakes our country made in its treatment of its black citizenry and working poor. Camae doesn’t trust humanity so well, at least not the white Americans who so stubbornly fail to live up to King’s ideals.

The play is fiction, but terribly real, until it morphs into magical realism. Camae, for one thing, isn’t quite a maid, and it may be up to interpretation whether some of what goes on in that room – a brush with the supernatural and perhaps communication with God herself (Camae informs us that God is a “she”) – is an extension of King’s own fevered dream.

At the end, a slideshow litany of pop culture and historical events that brings us to the present day is the show’s splashiest moment. But consider how King strived to get us to correct America’s terrible wrongs before he died at age 39 – entrenched racial discrimination, class divisions, economic disparities. Consider how we continue to witness violence against unarmed black teenagers, how our economy still fails hard-working Americans, how apt his speeches remain, and you will feel, as Portland Stage’s rapt audience surely did on opening night, how much it’s we who have missed him.

Daphne Howland is a freelance writer based in Portland.

Send questions/comments to the editors.