Bob Sprankle’s long fight to receive disability benefits from the state retirement system is finally over and the pain he endures is eased somewhat by the knowledge that his struggle could help others in similar situations.

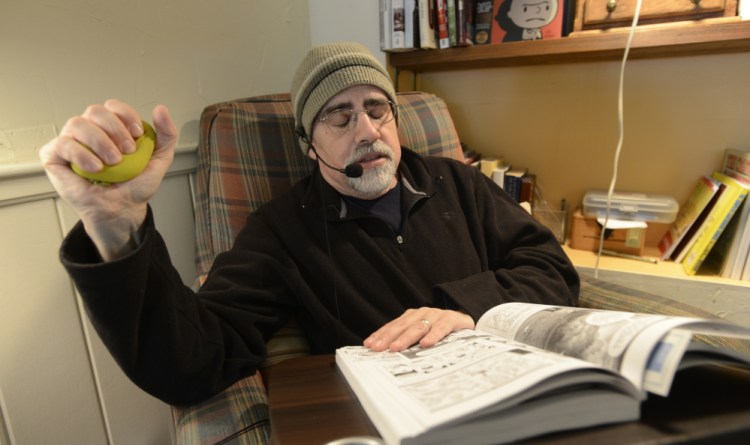

While Sprankle said Monday that he is still in “extreme agony” from his medical condition, he also is “overwhelmed” with gratitude that his two-year battle ended last week when the state retirement system granted him disability benefits.

Sprankle’s case also played a role in prompting Maine to consider reforms to its disability system to make it more flexible and better able to serve public employees who fall ill with diseases and conditions that keep them from working, said Rep. Robert Foley, R-Wells.

“This is like an enormous weight has been lifted from our shoulders,” said Sprankle, a former longtime Wells Elementary School technology teacher.

Sprankle credited Foley for assisting with his case – “Bob Foley is my hero,” he said – and the media for shining a spotlight on his condition and how the statewide system was in need of reform.

Sprankle, 52, suffers from chronic lower abdominal pain related to a 2007 hernia surgery, and is in so much pain that he is largely confined to his home in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. He has difficulty walking around the block.

Sprankle said he was invited to re-apply for disability after an Aug. 23 Maine Sunday Telegram story about his case that also delved into problems with the Maine Public Employees Retirement System.

The state reconsidered Sprankle’s case this fall, and this time granted him a permanent retirement disability.

“For Bob, this is a good and happy ending,” said Foley, who works in the insurance industry.

Sprankle is now eligible to receive 59 percent of his $71,000 income until he turns 65.

“We are pleased Mr. Sprankle is eligible to receive disability retirement benefits,” said Sandy Matheson, executive director of the retirement system. Matheson said she couldn’t get into the specifics of Sprankle’s case, citing patient confidentiality.

But Matheson said various reforms to the state system that are underway should help resolve cases fairly for public employees who qualify.

Foley said he’s encouraged that Matheson and others who work for the state retirement system realize its shortcomings and are willing to work with him to resolve the issues.

“They recognize that the system as it currently stands is not user-friendly for their customers,” Foley said.

Sprankle had been denied disability twice in a system that increasingly had become more likely to reject applicants since 2009, records show. Medical professionals and former co-workers vouched for Sprankle that his condition was debilitating.

Sprankle, after being denied disability in 2013, tried to return to Wells Elementary School for the 2014-15 school year.

But in November 2014 he left work permanently after the pain became unbearable and he could no longer walk the hallways, he said. Sprankle would lie down in a supply closet between periods to try to ease his pain and conserve energy for students.

About 150-250 people apply for disability every year. The percentage approved for disability has dropped from 75 percent in 2009 to 30 percent in 2014, according to state records.

Matheson told the Press Herald this summer that about five years ago, the state streamlined the process to give applicants quicker answers to their medical cases.

But the unintended consequence of the fast turnarounds was more denials, she has said. Foley said the state should offer a separate benefit, a long-term disability benefit distinct from the existing retirement disability offered by the state system. That would making the system better able to respond to applications.

The system’s current retirement disability is considered a retirement benefit. Applicants must prove they are permanently disabled, setting a higher bar than a long-term disability claim.

It’s also a higher standard than qualifying for Social Security disability. Employees in the state retirement system are barred from collecting Social Security disability because the state system is intended to replace Social Security.

Foley said a long-term disability benefit would cost public employees about $5 to $10 per month, and he has submitted legislation that would allow the Maine Public Employees Retirement System to offer the new benefit. Currently, the 60,000 public employees in the system pay 7.65 percent of their income into it, with most of that money paying for their retirement income.

“The standards for long-term disability would be easier to meet, because the idea is the employee may in the future be able to return to work,” Foley said. “If we had offered long-term disability, Bob could have easily qualified for that at the very beginning.”

Foley said employees who can’t work but who may not be permanently disabled would have another option, and the retirement board would not be saddled with difficult-to-decide cases.

Matheson said it would take time to implement, perhaps a year or so, but Foley’s suggestion is a “great idea.” The Maine Public Employees Retirement System is also working on reforms to determine why the review board had denied so many cases over the past five years. About 1,600 people collect retirement disability from the system.

Send questions/comments to the editors.