The idea of choosing a simple, self-sufficient life, away from the din and close to nature, is hardly new. Thoreau famously lived in a cabin near Walden Pond for two years, doing just that.

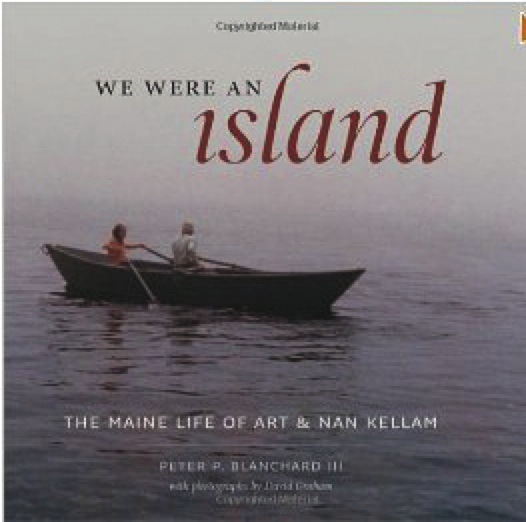

In the 150 years since, countless others have chosen to live off the land and off the grid. But few have achieved and documented such a long and radical retreat from the world as Art and Nan Kellam. Their four decades of living on Maine’s Placentia Island, as its sole tenants, form the basis of Peter Blanchard’s absorbing biography, “We Were an Island.”

This is no ordinary chronicle of island life, because the Kellams were no ordinary islanders. From the day of their wedding in 1935, this unorthodox couple from the Midwest had a plan: Not only did they want to get away from it all, they wanted a remote setting, preferably an island, for their future home. As Art described it, they sought “a place that both of us would be willing to marry, for better, for worse, for life.”

The couple’s far-reaching property search reveals both the method and madness of their quest. They considered islands off British Columbia, Washington and the St. Lawrence River Valley before honing in on Maine.

The Kellams covered their living room wall with maps, creating a mural of Maine’s coastline. Nan corresponded with several real estate agents in search of an island secluded enough that there would be no “possibility, even a remote one, of near neighbors.” Ditto for boat races and steamer routes. After visiting a handful of sites in 1948, they purchased Placentia Island in Blue Hill Bay, with its 552 acres of mixed terrain, spruce forests and shingle beaches. They paid $7,500.

Art, then 37, quit his engineering job at Lockheed in California, and they headed east.

On the face of it, the pair lived a spartan and solitary life. They converted an old barn for shelter and went without phone, electricity or running water — “impediments,” in their view. A wooden dory was their conduit to Bass Harbor, two miles away, where they rowed for supplies, library books and mail.

The Kellams left a rich and detailed archive of their time on Placentia, which the author puts to good use. Beyond the chores of island life — cutting wood, clearing paths, tending gardens — the couple enjoyed many pastimes together.

Among their daily rituals were meetings of their so-called Reading Club, where Art and Nan would read aloud to each other. They read classics by Dickens, Conrad, Tolstoy and others, as well as magazines — some 730 titles appeared in Nan’s journals over the years.

Ultimately, the Kellam’s tenure on the island altered some of their stated goals. These diehard loners who yearned to sequester themselves from the world, who regarded people’s visits as “invasions,” weren’t nearly as disengaged as they may have appeared. Art, who once praised his Lockheed job as “the next best thing to hermithood,” later came to refer to the couple as “the not-so-hermits.”

Nan, too, conceded that perhaps they had misgauged their own social barometer. “Looking backward,” she wrote, “it is almost hard to remember that this new world was planned with little thought to social relations, and most of that negative.”

Nor were the Kellams detached from the events of their day. A battery-powered radio relayed “Meet the Press” and other news to the island. “Rain, correspondence knitting, and McCarthy,” Nan wrote, in May 1954.

Such disparities may suggest a different truth about the pair — that seclusion, as such, was never truly their aim, but an extreme expression of it. Selective isolation — living on their own terms and calling the shots — seemed more to the point. As Blanchard notes, finding that balance was key.

“We Were an Island” is, at once, a love story and a tribute to the singular experiment that the Kellams pursued. Still, readers may ponder the many paradoxes of the couple’s full and venturesome life.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays, and book reviews for numerous publications. She lives in Kennebunk.

Send questions/comments to the editors.