If I could see the weedy mussels

Crusting the wrecked and rotting hulls

– From “Exile” by Edna St. Vincent Millay

CASCO BAY — The survey map in Ann Thayer’s hand showed fat red splotches that wrapped around two-thirds of Bangs Island’s shoreline, meaning that the intertidal zone – the zone between the high and low water marks – was supposed to be densely packed with mussel beds. The tide was nearly three hours past high, leaving plenty of rockweed exposed.

Thayer began systematically flipping over the weed, looking for mussels, aka Mytilus edulis, attached to the rock below.

“Nothing,” she said. She said this over and over.

By the time she got back into her dinghy to row back to her Boston Whaler, she’d found only two mussels. Two where surveys from the 1970s and 1990s indicated there should be thousands, mollusks wedged into almost every nook and cranny in the rocks, the blue-hued shellfish nearly as commonplace as the barnacles living on their shells.

Thayer, who serves on the board of directors of Friends of Casco Bay, was not surprised by her findings.

They repeated what she’s been seeing since 2013, when she started surveying, with the help of other volunteers, the dwindling mussel population of Casco Bay. More than half the surveyed sites have yielded no mussels where once there were plenty.

Up the coast, say in Hancock County, mussels can still be found in the intertidal zone. But another recently completed survey of 20 locations all along the state’s coastline by Cascade Sorte, a former University of Massachusetts Boston professor now at University of California Irvine, was equally disheartening. Sorte hasn’t crunched all the numbers yet, but the problem seems to be across the board in Maine.

“It used to be that mussels were covering over half the space in the intertidal zone,” Sorte said. “More than 50 percent of the space and now they are covering typically less than 10 percent. They have gone from this species that basically defined the rocky coastline to being a minor part of it.”

Minor as in, nearly gone from the shores of Bangs Island. And here’s the confusing bit: Maybe a 10-minute lazy breast stroke away is the Bangs Island Mussel Farm, where cultivated mussels grow on ropes stretching down into the cool sea.

They can grow on mussel farms, whether on the bottom or on ropes, but they aren’t growing in the intertidal zone. There’s enough seed, or spat, for farmers to grow them. But they’re not ending up on shore the way they used to.

The big mystery is why? Without knowing that, nothing will be reversed – if, in fact, it still can.

TRUE DETECTIVE

On this island trip – she’s taken many, and is always looking for new volunteers to help with the ongoing survey – at least Thayer hadn’t heard the noise.

“Scurrying,” she said. “Last year you’d flip over the weed, and you’d hear the noise of the green crabs scuttling away.”

She found three green crabs under the weed and immediately dispatched the one she managed to catch. No sense in leaving it alive; even if the crabs aren’t the only culprit behind Maine’s disappearing mussels, most consider them to be at least a part of the problem.

Other factors that are being considered by the sleuthing environmentalists and marine biologists working on this mystery include warming temperatures, ocean acidification, hungry eider ducks, predatory jellyfish eating the mussels in their larval stage, sea squirts, bacterial diseases, hard winters that rough up the intertidal zone, the impact of dragging on the mussel beds in past decades and changes to the substrate where mussels typically grow.

For every mussel expert you talk to, you’ll hear a slightly different combination of which of these is doing the most harm.

If you look at the numbers game in that random August afternoon search on Bangs Island, you’d point to the green crabs, outnumbering mussels 3 to 2.

But Sorte, the professor who surveyed for mussels in 20 locations across the coast – all the way to West Quoddy Head in Lubec – between 2011 and 2014, said the groups she worked with did not see that many green crabs. “They have been seen as the culprits in a lot of locations, but we don’t have early data to support that,” Sorte said. (Her final data will be available in about six months.)

Thayer’s volunteers occasionally do their surveying by boat or kayak, as well as on foot. Sorte’s group, mostly graduate students looking for field experience, did all their surveying by foot, with a team of at least six. They would put down measuring tapes and count mussels at even intervals. Four of the sites had been surveyed before, 16 were new sites since Sorte hoped to establish a baseline where none had previously existed. In the past, when mussels were abundant and worries were scarce, no one was counting.

Still, Sorte doesn’t dismiss the green crabs as a factor. Or fluctuating temperatures on either end. “There are issues with ice scour,” she said. “That is where the sea water freezes, and then you have these rafts that are rubbing around the rocks.”

FROM HEAT TO DUCKS

“I don’t think anyone really knows,” said Carter Newell, founder of Pemaquid Mussel Farms, which has operations from Stonington to Lamoine. He also set up the original Bangs Island operation and served as a biologist for Great Eastern, the mussel producers who made the Maine mussel fashionable in the early 1980s, back when The New York Times dubbed them “the mollusk of the moment.” “So everyone is going to pick their favorite theory, right?”

Or theories. Take Tollef Olson. He started Bangs Island Mussel Farm, sold that, got into kelp farming with Ocean Approved, recently sold that and is working on a new kelp-related product. He’s also a surfer and like Thayer, serves on the board of directors of Friends of Casco Bay. Warming ocean temperatures – the Gulf of Maine is the fastest warming body of ocean water in the world – could be a factor. “Mussels do have a temperature range they are comfortable with.”

He’s unsure what role acidification may be playing but says it’s less obvious than it is with soft-shell clams. “I haven’t seen the pitting,” he said, referring to the degradation of the clam’s shell. He added that clams, sitting in the mud rather than on it, as many mussels tend to grow, are more vulnerable because they are “encapsulated in an acidic environment.”

Studies have found a connection between ocean acidification, caused by greenhouse gas emissions, and the weakening of a key component to a mussel’s survival, the byssal threads (fibers of protein) that the mussels use to attach to rocks, docks and even the ocean bottom.

The intense amount of dragging that happened in the 1980s is also likely to have had an impact, Olson said, both in disrupting the substrate the mussels need to develop beds and depleting the population. He’s seen the evidence firsthand when he’s been diving, looking for undiscovered beds. “Back then people weren’t thinking that way,” he said. “So I am not speaking badly about them. Sometimes you don’t know the effect of overfishing until later.”

Not to be forgotten, Olson says, are the green crabs and another predator that likes to feed on mussels. “I have seen a huge increase in the number of eider ducks,” Olson said. “They were hunted up through the 1960s, really hard, and now they’ve made a comeback in the last 15 years.”

“They can literally eat their weight in mussels in a day,” he added.

VOLUME AND VALUE

Poet Mary Oliver wrote of gathering mussels “in barnacled fistfuls” in “Mussels” – “I reach forward into the dampness, my hands feeling everywhere for the best, the biggest.” She published that poem in 1977. That was the year after Phil Gray started reaching into the dampness, foraging and then making his living from mussel harvesting.

He’d grown up in central Maine, his dad working at a paper mill in Millinocket. The way the economy revolved around the paper industry made Gray long for something more. He was a young man, reading Euell Gibbons, and in 1976 decided to go to the coast, joking that he was “stalking the blue-eyed scallop.” But the blue-shelled mussel turned out to be his main prey. “They were so plentiful,” he marveled.

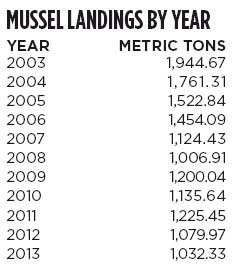

That was the beginning of the uptick in landings. In 1975, Maine fishermen brought in 3.59 million pounds of mussels in the shell. In 1976, that number went up to 7 million and by 1977, they harvested 12.4 million pounds. Others were dragging, but Gray liked hand harvesting. “I felt I could put out a better product.”

The numbers continued to climb as Maine mussels grew in popularity until volumewise (but not valuewise) mussel landings were outpacing those of soft-shell clams.

In Gray’s heyday, he’d get about 100 bushels of mussels, or 5,000 pounds in a week. These days he’s lucky to get 50 pounds, which he sells at farmers markets in Brunswick.

“A couple of times I had to buy mussels,” Gray said. Even that hasn’t been easy. “I have actually ended up selling Prince Edward Island mussels.”

He won’t do that again, though; he’d prefer to harvest soft shells and increasingly quahogs, which have shells tough enough to resist the onslaught of green crabs and are still thriving. And he does have cause for optimism: he recently found a few small pockets of wild mussels in the waters off Harpswell, including “the largest set of wild mussels that I have seen in eight years.”

They’re larger than what he’s used to seeing, and he thinks natural selection is very much at play in the shift in where the mussels live.

Gray, 68, believes himself to be the last harvester of wild mussels in southern Maine. He might be right, said Denis-Marc Nault, supervisor with the Maine Department of Marine Resources’ Division of Shellfish Management. “Wild harvesters are fewer and farther in between,” he said. “Maybe three or four maximum are still hand harvesting (throughout the state).”

There are between 28 and 30 licensed harvesters in the state now, the bulk Down East and draggers. Nault said it’s too hard to say whether farming outpaces wild harvesting these days.

In terms of poundage, mussels are the fifth biggest fishery in Maine; still, they represent just 4 percent of the total catch according to 2014 Department of Marine Resources data, way behind lobster (40 percent). And Nault is quick to point out that when it comes to value, mussels are way down the chain. They rank 11th behind oysters, urchins and – oh the ignominy – worms.

THE PEOPLE’S SEAFOOD

The dwindling number of wild mussels on Maine’s shores troubles environmentalists, marine biologists and fishermen. It might be even more disturbing if it weren’t for those thriving mussel farms.

But the steady decline in the intertidal zone also has an impact on coastal residents and visitors who wonder why the rocks seem so naked, why wading into their old swimming spots no longer involves navigating the hazards of sharp-shelled mussels growing fat in the flats. Or why Shaw’s and Hannaford have more mussels than Mere Point or Maquoit Bay.

Blue mussels have been, for these last decades of heavily regulated ocean resources, the people’s seafood, the living food you could take home from the seashore along with sea glass and a sunburn.

Unregulated by municipalities, which claim clams, but not the less desired mussel in the intertidal zone, the mollusks are literally ours for the picking (provided no red tide has shut down the coastline). Or they were.

“It’s always been that you could just go out at low tide and get some mussels,” said Cathy Ramsdell, executive director of Friends of Casco Bay. “But you can’t do that anymore because you can’t find them.”

That vanishing act is the kind of thing that gets people worried. “A lot of us are thinking, what kind of time bomb is ticking?” Ramsdell added.

And so they call Ann Thayer and ask her to come over and look at their empty rocks with them. They ask their scientist friends. They call the Department of Marine Resources, which hasn’t had the funding, or the manpower, to survey the mussel population for years.

“It’s 150,000 intertidal acres,” Nault said. “That is a near impossible task for myself and the other mussel specialist.”

Nault said he hopes to partner with mussel harvesters and others to do aerial mapping of the beds next year, maybe pulling in students from area colleges. He wants answers, as well.

“As scientists we have to rule out everything,” Nault said. “We can’t just say, ‘Oh, the green crabs got them.’ ”

Sorte’s research in mussel populations extends beyond the Northeast; she’s also working on studies of European, New Zealand and West Coast populations of the mollusk, as fast as she can.

“It is just a foundation species of rocky intertidal habitat through the world,” Sorte said. “It’s important because when it is gone, it is gone. And how will that affect the rest of the ocean community?”

Send questions/comments to the editors.