Ethar Milliken, a pious and hardworking farmer who had served his country in the First World War, lay in bed pondering what would become of his two farms in Kennebunkport.

As the great fires of 1947 swept across York County, he had fought back the flames from his land and suffered a heart attack. Doctors told him he would never again be able to work sunup to sundown on his farms. As he recuperated, he dwelled not on what he might lose but on how to repay God for all the good in his life.

Milliken had read about the plight of refugee families in Europe living in overcrowded camps, dreaming of making a new life for themselves somewhere else, and knew he could help. For more than two dozen of those refugees, that somewhere else became one of Milliken’s farms in a quiet, small town on the coast of Maine.

From 1949 to 1955, Milliken’s Freedom Farm on Arundel Road offered a home and livelihood to refugees from Ukraine, Estonia and Poland who fled war and work camps in Eastern Europe. Some had been prisoners of war. Around 30 immigrants — six families and six single men — began their lives in America at the farm in Kennebunkport. Some later settled in East Pittston, where Ukrainian families formed a farming community.

Ants Parna, his wife, Agnes, and their 10-year-old daughter, Lembi, were the first refugees to arrive at Freedom Farm. They came from Tallinn, Estonia, where he worked in a shoe factory until the city was occupied by Russian soldiers in 1940. Photo courtesy of the Kennebunkport Historical Society

Sharon Cummins, the historian at the Kennebunkport Historical Society, first heard the story of Freedom Farm years ago and has researched how it came to be and the people who lived there. As she has watched Ukrainians suffer in the Russian invasion, she has thought back to Milliken and those who found a home at Freedom Farm more than 70 years ago.

“I’ve been thinking about how one person was able to make a difference with extraordinary generosity,” she said. “I just hope that something like that could happen again.”

Cummins recently wrote about Freedom Farm and shared photos of the families that lived there in a post on the historical society’s Facebook page. The story of Freedom Farm has not been forgotten in Kennebunkport, she said, but she wanted to highlight the generosity of Milliken and his wife, Vera Stone Milliken, at a time when Ukrainians are once again forced to flee war.

“Ethar was a very pious, humble guy,” Cummins said. “I’ve heard so many people say he was always like that. This wasn’t a one-time thing.”

After Milliken decided to use his second farm to help others, he turned it over to the United Baptist Convention of Maine. Freedom Farm became a statewide project, with cooperation from the Federal Displaced Persons Bureau. All of the Freedom Farm families came through American displaced persons camps in Germany, where life was mere survival, Cummins said.

There was a little local resistance to Milliken’s plan, but it didn’t last.

“People were probably still reeling from World War II and thinking about what it meant to have foreigners in town,” Cummins said. “But they really came around and offered a tremendous amount of support.”

Before families could move in, there was plenty of work to be done on the 156-acre farm, especially to the 11-room farmhouse that would be converted into three apartments.

“With true New England thoroughness, housewives scrubbed the farmhouse floors; husbands painted and papered walls. A crew of ministers shingled the roof,” Robert Montgomery recounted in a 1954 Christian publication called Guideposts.

The Baptist Youth Fellowship raised money to buy a team of horses and a church in Farmington Falls provided a cow. Other gifts poured in: 25 hens, a cat and dog, canned goods and clothing.

In June 1949, the first families moved to Freedom Farm.

FINDING FREEDOM ON THE FARM

Ants Parna, his wife, Agnes, and their 10-year-old daughter, Lembi, were the first to arrive. They had fled Estonia just in time to miss being forced into a Russian work camp. They traveled by foot and hidden in a freight car, begging for food and eating raw potatoes that Parna was able to forage at night. By the time they reached an American camp in the U.S. zone of Germany, Lembi was nearly blind from malnourishment. Her eyesight was restored within a few months of coming to Maine.

Parna, who had been a supervisor in a shoe factory, arrived too late in the season to plant crops. Three local ministers helped harvest a bumper crop of hay worth $2,500 to get Freedom Farm off to a good start.

“God is taking care of these people,” Milliken said, according to Guideposts.

A month after the Parnas arrived, a dedication service was held at Freedom Farm to honor the “Americans-to-be,” a name the Baptists preferred to displaced persons. Agnes Parna was asked what she thought of her adopted country, according to Montgomery’s Guideposts story.

Mrs. Wassily Gontschar, shown in photos from a 1951 Portland Sunday Telegram story, came with her family from Ukraine to Maine, where they lived first at Freedom Farm in Kennebunkport. They later settled on a farm in East Pittston. Photo courtesy of the Kennebunkport Historical Society

“Happy land!” she replied, grinning broadly.

That fall, two more families were welcomed to Freedom Farm. Mr. and Mrs. Mykola Wolotschaj and their 3-year-old son, Ivan, came from Poland, which was occupied first by Communist Russia and then Nazi Germany.

Wassily and Eugenie Gontschar and their 21-year-old son, Mykola, were from Otyniia, Ukraine, and had spent four years in displaced persons camps. Their two teenage sons had been taken to a German labor camp and were never heard from again. Her parents also were killed, according to Cummins. In 1944, Wassily Gontschar, his wife and older son were taken by Germans, but ended up with Americans before they could be forced into labor camps.

After living at Freedom Farm and adjusting to life in America, the Ukrainian couple moved to a farm in Kennebec County. Their son, who now went by Mike, got a job as a porter at Maine General Hospital in Portland.

Mike Gontschar spoke little English when he started his job, but learned quickly through demonstration, according to a 1950 article in the Portland Press Herald.

“But once he learned it, he never forgot; he never had to be told again how to do something; he never had to be told again where a place was,” Roger V. Snow wrote. The younger Gontschar took English classes at Portland Evening School and made plans to further his education.

The Wowk family from Ukraine was the last to arrive at Freedom Farm. Alexander Wowk, a farmer, had lost an eye from torture. His parents and six siblings were all killed by the communists. Wowk came to Maine with his wife, Etuhenija, and their young children, Alec and Ludmilla, who were born in a displaced persons camp in Germany.

A week after arriving at Freedom Farm, Etuhenija Wowk watched her two children playing in the sun, Montgomery recounted in Guideposts.

“America is what I thought heaven would be like,” she said.

A NEW LIFE IN KENNEBEC COUNTY

The Wowks stayed only a few months at Freedom Farm before moving to East Pittston. They were among 11 families – nine from Ukraine and two from Russia – that settled in farms in the small Kennebec County town. They worked dawn to dusk.

Many of the families were brought to Maine by K.V. Poushental, a Pittston man who worked in real estate and saw an opportunity to improve farmland and provide homes for refugees who needed them. He contacted a New York City refugee center and tried to bring together families of the same faith. All of the new residents were devout Baptists.

A Portland Sunday Telegram magazine article from Sept. 16, 1951, highlighted Ukrainian families who settled on farms in East Pittston in Kennebec County. Some had previously lived at Freedom Farm in Kennebunkport. Scan courtesy of the Kennebunkport Historical Society

“Years of hardship and trial are etched in the faces of the newcomers who have survived both the Bolshevik persecutions and Nazi slave labor camps,” Margaret Frazier wrote in a 1951 Portland Sunday Telegram article.

Frazier described how a scattering of “desolate East Pittston farms looked like heaven” to the 50 displaced persons and war refugees who settled on them. All had been in camps before coming to the United States.

“Although they still instinctively shrink at the sound of a police siren, half expecting someone to descend upon their refuge and snatch them, or it from them, they declare they already ‘feel’ the freedom they sought and are grateful to be in America,” Frazier wrote.

The families caught barrels of fish from the Eastern River, cut their hayfields and went about canning and preserving garden produce and wild fruit in preparation for winter. Some arrived too late in the season to plant gardens and instead took in out-of-state summer guests. They filled their homes with furniture discarded by neighbors or brought home from the dump and refurbished.

“The ramshackle Pittston farms soon may look like heaven to anyone at the rate these industrious people are progressing,” Frazier wrote. “With some of them here only weeks or months, they have repaired the buildings, cleaned up the property, planted gardens and installed fowl and livestock.”

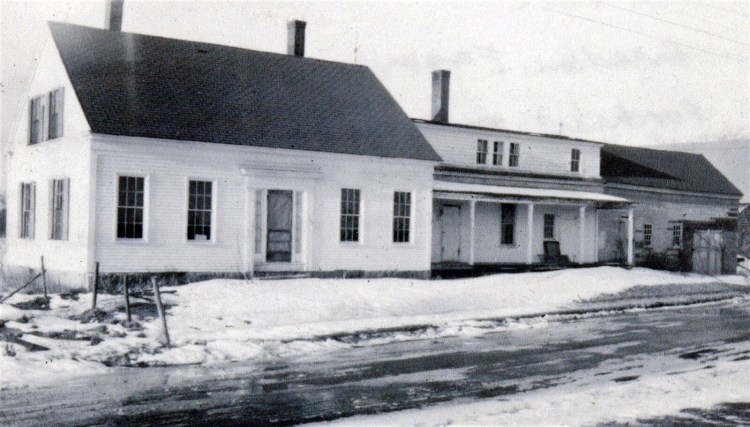

The farmhouse at Freedom Farm burned to the ground in 1968. The barn has since been converted to a private residence. Photo courtesy of the Kennebunkport Historical Society

Neighbors along Stilphen Road grew used to hearing hymns coming from the families’ homes. Their church services were spirited, neighbors told the Telegram, and grew happier over time.

“‘God bless America and the people of America’ figures prominently in their prayers, and the former Ukrainian people shed tears of gratitude for their own improved fortunes and tears of grief for their lost relatives,” Frazier wrote.

A year after the last refugee family left Freedom Farm, Ethar Milliken died. The farmhouse was sold in 1963 and burned to the ground on Jan. 28, 1968. The barn has since been turned into a private residence.

“Only the barn remains to remind us of Ethar Milliken’s gift and the shattered lives it changed,” Cummins said.

And, perhaps, the descendants of the people he helped.

Send questions/comments to the editors.