Second of two parts: read part one here.

In the summer of 2011, officials from three Louisiana financing firms came to Maine to lay the foundation for a community investment program that three years later would eventually put millions of taxpayer dollars into their pockets.

The firms – Stonehenge, Enhanced and Advantage Capital – are in the business of using government subsidies to arrange financing for companies in low-income communities. But first, they persuade state legislatures to create these subsidized tax-credit programs that eventually benefit their clients. The financiers then draft laws, lobby legislators for their passage and contribute liberally to political campaigns.

Maine’s rural, citizen-led legislature and its shortage of sophisticated lawmakers makes it attractive to the architects of these programs, according to those who have followed them.

Stonehenge and its counterparts have orchestrated 10 deals in Maine totaling $195 million in investments under the Maine New Markets Capital Investment program. The arrangement requires that Maine taxpayers give the investors 39 cents for every dollar invested, for a total of $76 million to date.

A five-month Maine Sunday Telegram examination shows that nearly half of what was invested in low-income communities – $91 million on paper – never made its way to the designated companies for new upgrades or expansions. Instead, the money was used to pay off old loans or stayed on the books for less than 24 hours.

Five of the 10 deals used a questionable financing instrument called a one-day loan where $64.4 million flowed in and out of the businesses in the form of one-day loans – issued by a lender and paid off the very same day. Only $6.7 million made its way to the designated businesses to use in upgrades, expansions or other new uses. Still, Maine taxpayers are on the hook to pay $38.5 million to the investors who financed the deals.

The point of the one-day loan is to inflate the total value of the financing package in order to trigger the highest possible tax credits. The bigger the deal, the more taxpayer dollars go to the investors.

And it’s all legal.

Roger Katz, a Republican senator from Augusta and co-chairman of the Government Oversight Committee, said in retrospect he’s sorry he voted for the bill to create the program.

“Collectively all the various parties involved in this ought to get an F for what happened, and that certainly includes the Legislature,” he said, adding that the oversight committee is now considering holding a public hearing to start a process to make sure it doesn’t happen again.

The most egregious example of the one-day loan occurred in 2012 when $40 million was ostensibly committed to revive Great Northern Paper – a foundering paper mill in East Millinocket owned by private equity firm Cate Street Capital of New Hampshire. Of that $40 million, more than $32 million was in the form of one-day loans, $7 million paid off existing high-interest debt and $1 million went to brokers’ fees. None was used to upgrade or modernize the mill as intended in the company’s application to the New Markets program. The mill went bankrupt and more than 200 people lost their jobs, but Maine taxpayers will be paying investors $16 million through 2019.

The financing firms that came to Maine to set up these tax credit programs have done so in other states. Modeled after a federal program, they all promise to direct outside investment to the poorest parts of a state. But the success of the New Markets programs elsewhere has been spotty, with at least one state opting to cancel the program outright and others trying to do so. And now the federal program that provided a template for the state plan is under scrutiny from the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

“It’s a very similar pattern of hardball lobbying, a lot of outlays at the state level, to get these bills passed that will benefit pretty much just them,” said Julia Sass Rubin, a professor at Rutgers University who studies community economic development programs. “They’ve learned to live off taxpayers very effectively.”

Rubin has had Stonehenge and its two Louisiana companion firms, Enhanced Capital and Advantage Capital, on her radar for more than a decade and has watched them go from state to state creating these types of programs.

Stonehenge, Enhanced and Advantage didn’t respond to repeated requests for interviews.

Louisiana financiers first appeared in Augusta in 2009 when their representatives lobbied for a precursor to the New Markets tax credit program that had been passed in other states. But their efforts failed.

Two years later, representatives from Stonehenge approached local attorney Chris Howard of the Pierce Atwood law firm to draft language for a bill that would establish the program. Then-Senate President Kevin Raye agreed to sponsor it.

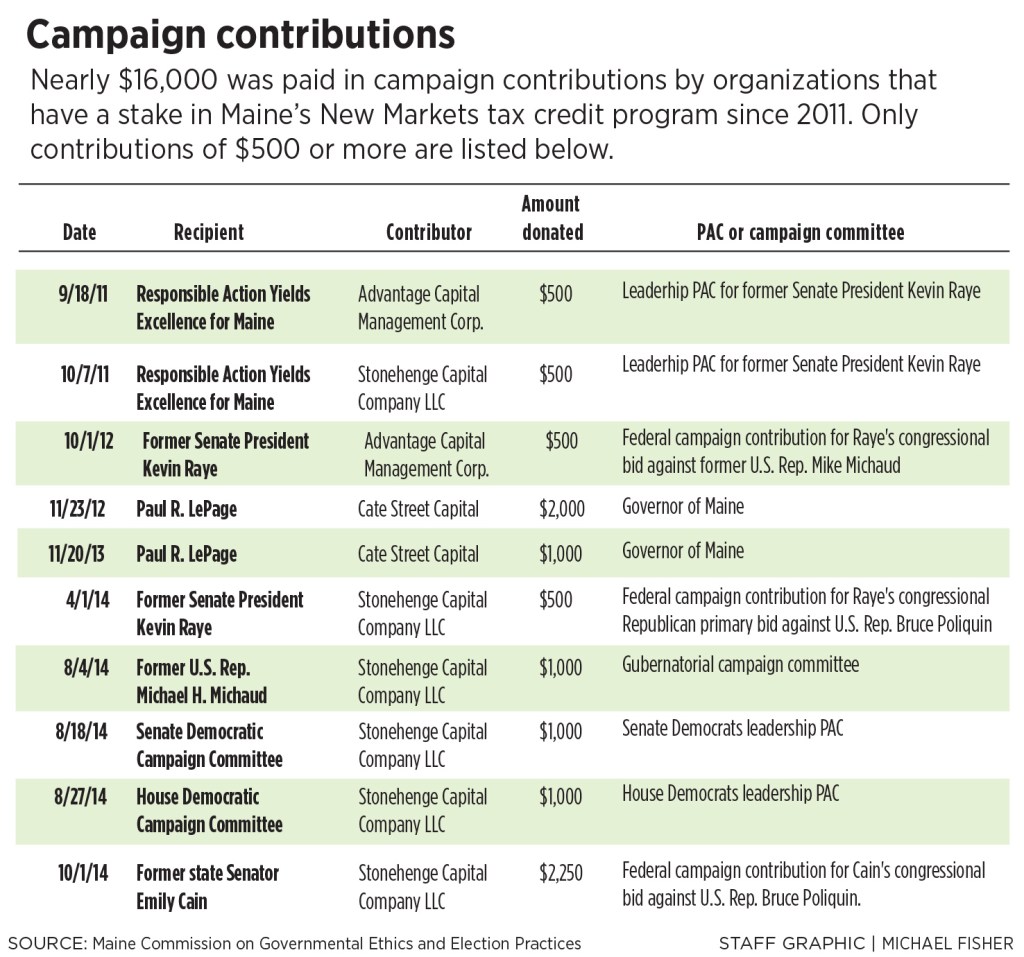

The three financial firms then hired Josh Tardy, the Republican House leader from 2006 to 2010, to lobby legislators to encourage the bill’s passage. They also made roughly $16,000 in campaign contributions to the bill’s sponsors and to legislative leadership. That bill, L.D. 991, was approved and its language was ultimately wrapped into the state budget.

At the time, the lawmakers responsible for the program didn’t envision a situation where the investors would get back more in tax refunds than the businesses received in direct investment. But the complexity of the program and the number of players involved in the financing creates a morass of financial mumbo-jumbo and makes it vulnerable to exploitation, according to interviews with dozens of financial experts.

Despite the problems, a bill is now making its way through the Legislature that would expand the money available under the program. The Finance Authority of Maine, or FAME, the agency that administers the program, has introduced an amendment to L.D. 297 to eliminate the use of one-day loans.

A QUESTIONABLE FINANCING TOOL

The Great Northern Paper deal was the first to use a one-day loan that resulted in more taxpayer money being sent to investors than was received by the low-income community business. But it wasn’t the last.

John Burns, director of the Maine Venture Fund, has been putting together financing deals for 15 years, but had never heard of a one-day loan before having the Maine New Markets Capital Investment program explained to him. But the purpose is clear, he says.

“No one makes a one-day loan for any reason other than as a mechanism to make something else happen, or to put something on somebody’s books for a short amount of time,” he says. “It’s a tool, … it’s not a standard financing product for lenders.”

Charles Colgan, a former state economist and professor of public policy at the Muskie School of Public Service at the University of Southern Maine, hadn’t heard of a one-day loan before the Great Northern deal was explained to him. But he wasn’t surprised.

“This is financial engineering in the 21st century,” Colgan said. “This is the way deals are engineered to take advantage of tax law, and it’s true of state law and federal law.”

The federal New Markets program also offers a 39 percent tax credit, but there’s one big difference. In Maine’s program, the tax credits are refundable, which means the investor can redeem them for cash if they don’t pay any Maine income taxes.

The federal and state governments determine a finite amount of tax credits that taxpayers ought to bear – in Maine’s case the credits are capped at $97.5 million, but the Legislature is considering doubling that to $195 million through L.D. 297. The tax credits – which in the Maine program are redeemable over seven years – are then allocated to financing agencies, known as community development entities, or CDEs. Stonehenge, Advantage and Enhanced are all CDEs.

It’s the CDEs that act as middlemen – matching businesses in distressed communities with investors who want the tax credits. They also arrange the financing, including the one-day loans.

In addition to Great Northern, here are the other four deals approved by FAME that used one-day loans:

• In May 2013, Midwest Community Development Fund II, a CDE affiliated with Advantage Capital, invested roughly $24.8 million in JSI Store Fixtures, a manufacturer in Milo. The board approval came despite a recommendation from FAME staff to reject it because of the one-day loan. Of the total investment figure, $15.8 million was immediately returned to Advantage Capital in a one-day loan and the remaining money was used to refinance high-cost debt. That deal will trigger $9.7 million in taxpayer payouts.

• In January 2014, a CDE that is a subsidiary of U.S. Bank (which is involved in every aspect of New Markets deals as a lender, investor and middleman) got the OK to invest $10.1 million in Nova Seafood to allow the seafood distributor, located on Commercial Street in Portland, to open three seafood restaurants in the city. However, $7.5 million of that total investment is a one-day loan that would leave Nova Seafood with $2.5 million. Meanwhile, taxpayers would be on the hook to pay $3.9 million. This deal has not officially closed. Angelo Ciocca, Nova Seafood’s owner, said his restaurants are stuck in permitting, so the tax credits have not been released to the investor.

• Also in January 2014, the same U.S. Bank subsidiary was approved for a $10.2 million investment in a facility at Brunswick Landing that serves autistic children, which involved a one-day $1.7 million “bridge equity.” Similar to a one-day loan, the bridge equity was used to leverage tax credits and immediately returned to the U.S. Bank subsidiary. After more than $6 million was used to pay old debt and brokers’ fees, the company was left with $1.7 million. It will trigger a $3.97 million tax credit.

• In December 2014, CEI Capital Management, Maine’s only CDE, got the OK to invest $10 million in the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, which wanted to renovate its museum and grounds. This is a complex deal that also included federal New Markets tax credits, but on the $10 million Maine side of the investment, $7.4 million was a one-day loan, which left the museum with $2.5 million to invest. The deal will cost taxpayers $3.9 million.

While the use of one-day loans in the Great Northern, JSI Store Fixtures, and Nova Seafood deals appears to be at odds with the intent of the program, not all deals that use them should be painted with the same brush, according to Charlie Spies, CEO at CEI Capital Management, a Portland-based firm that, like Stonehenge and Enhanced, arranges investments using the New Markets program.

When used correctly, one-day loans have a legitimate function, said Spies, who offered the Farnsworth deal as an example.

Farnsworth wanted to renovate its museum and grounds, but didn’t have the cash flow to secure conventional financing because 96 percent of its assets were tied up in endowments for the art and real estate. CEI Capital Management used a one-day loan to release the value of those assets, he said.

“What we were able to do then was take some existing value they had in their real estate and basically release that with an appraisal and a loan against it using a one-day loan structure,” Spies said. “And that’s a situation where now they can go forward with those improvements where before they really had no other place to turn.”

The investment deal, which closed earlier this year, will allow the museum to make capital improvements and avoid serious budget cuts that would put at risk 39 full-time staff members at the museum, according to CEI Capital Management’s application to FAME. Even so, the New Markets deal will cost taxpayers more than the initial investment Farnsworth received.

Christopher Roney, the general counsel for FAME, does not believe legislators envisioned, let alone intended, that financing agencies would use one-day loans when they created the program. He has called for new rules to prevent their use, which state lawmakers are considering now.

“We have grown concerned about some instances of ‘one-day loans’ and simple transfers of existing businesses between owners, where investors obtain valuable tax credits for investments that do not result in a commensurate amount of additional spending on goods or services in the low-income communities where the businesses are located,” Roney testified on March 3 at a public hearing on the tax credit program’s expansion.

Spies, though he defended the Farnsworth deal, said he supports FAME’s attempts to change the law to disallow similar deals using one-day loans in the future.

Gov. Paul LePage, who supported the creation of the program to help the East Millinocket mill, said Tuesday through a spokeswoman that the changes proposed by FAME are “good first steps.” On Friday, he declined to expand, but intends to respond more fully in an op-ed to this newspaper, expected this week.

OTHER PROGRAMS, OTHER STATES

Maine is not the only state debating the worth of its New Markets tax credit program. Fourteen other states have their own variations, some of which were created by the same trio of financing firms – Stonehenge, Enhanced and Advantage – that appeared in Maine four years ago. Stonehenge and Advantage cut their teeth on how to persuade state lawmakers to adopt tax credit programs first with CAPCO, a widely criticized program that offers credits to insurance companies that fund investments to small businesses. The firms pushed CAPCO programs through the 1990s before turning their attention more recently to New Markets.

A 15th state, Georgia, recently approved legislation to create its own state-level New Markets tax credit program – five months after Stonehenge gave $20,000 to the Georgia Republican Party, which controls the state’s General Assembly. This despite opinions that Georgia’s program “is expensive, overly complex and a massive tax break for insurance companies with little to no economic benefit in return,” according to Wesley Sharpe, a policy analyst at the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute.

At least one state has already rid itself of its New Markets program. Missouri chose not to renew its program in 2013.

While the Missouri program’s supporters claimed it had created nearly 6,000 new jobs since it was launched in 2007, the Missouri Department of Economic Development’s own study concluded that the state’s $120 million investment created only 823 actual new jobs.

A little farther south, Arkansas legislators are considering a bill to eliminate its New Markets program, only two years after it was created in 2013.

As in Maine, Stonehenge, Enhanced and Advantage were all involved in lobbying for the creation of the Arkansas program, according to Grant Tennille, the former director of the Arkansas Economic Development Commission.

Tennille said he opposed the creation of the program from the beginning, but the bill had 70 co-sponsors and too much momentum to stop.

“Like most of them, it had one of those great names,” Tennille said. “I think ours was the New Market Job Act and the subtitle said all kinds of things about creating economic opportunity, particularly in areas of the state that haven’t had access to it before.”

Tennille said the lobbying efforts by the CDEs were impressive – “It became the Lobbyist Employment Act.”

Like FAME, his agency was tasked with administering the program. And like Maine, it’s a state with a small population and not a lot of demand for deals that can’t be handled through conventional financing like bank loans.

As a result, the CDEs “started getting goofy creative trying to slide projects by us and we managed to rebuff pretty much all of them.”

“I’m not going to tell you that all the projects that got done are bad projects,” Tennille said. “There are some great ones. My objection all along has been that this is a woefully inefficient way for the state government of Arkansas to try to inject capital into the economy. … Half (of the money) is disappearing into the maw of financial institutions and lawyers.”

He argues that the authority to issue tax credits should be taken away from for-profit CDEs and instead be given to state agencies – like Maine’s FAME – that already assist businesses in securing financing.

“Let them market (the tax credits) and we’ll put 100 percent of the money we get back into deals,” Tennille said. “Because that’s our job. We get paid a salary to put money into the deals and none of us get to go in and scrape off our management fee or our consulting fee or any of those sorts of things.”

Florida and Arkansas created state-level New Markets programs in 2013. Texas legislators considered creating a New Markets program that year, but the bill failed to pass. Other states, such as Massachusetts, are currently considering creating their own programs.

WHO’S MINDING THE STORE?

At the public hearing last month to expand Maine’s program, it was apparent that members of the legislative committee overseeing the expansion of the New Markets program didn’t understand its complexities. The fact the tax credits are refundable, for example, wasn’t mentioned.

Of the 13 members of the labor committee, none has a background in banking, accounting or investing. As representatives of a citizen legislature, the members represent a cross section of people from the general public, including mechanics, office managers and building contractors.

“I’m having a hard time following. This is like nothing I’ve worked on in my life,” said Rep. Paul Gilbert, a Democrat and retired supermarket manager from Jay, and a member of the labor committee. “I don’t think anybody on the committee was aware of anything like this. That one-day loan is baffling to me. It doesn’t sound right.”

A lack of sophistication among lawmakers is one reason the engineers of the New Markets program came to Maine in the first place, according to Rutgers’ Rubin and Arkansas’ Tennille.

“I’m betting that again Maine looks a little bit like Arkansas in that there are probably not many appointees to the FAME board who are forensic accountants or heavy-duty investment bankers,” Tennille said. “Very, very few human beings are able to understand one of these (deals) on its face with the stuff those folks are going to tell you until you unpack all of it and say, ‘Hang on a second, this is all phony baloney accounting tricks.’ It’s just hard to find. What everybody wants to believe is, ‘Oh, look! We found a way to turn $16 million into $40 million and pump it into the paper mill. Good for us. Aren’t we smart?'”

Peter Mills, a widely respected lawmaker when he served in the Maine Legislature from 1995 to 2010 and now the head of the Maine Turnpike Authority, said the lack of financial acumen among lawmakers concerns him, especially as it applies to legislation as complicated as New Markets. He said when he served in Augusta there were, on average, about 15 lawyers in the Legislature and now there are four or five.

“Most of the people in the Legislature – me included – have remarkably little experience in high finance and it’s getting worse,” Mills said, adding that the most important class he ever took was one on double-entry bookkeeping while he was in the Navy 50 years ago. “Just that little bit (of knowledge) has kept me out of trouble at various levels my whole life. I’m astonished by the sophistication of the financing tools available. At least I know enough to ask the right questions.

“It is hard to understand how the one-day loan shenanigans worked exactly, but it leaves egg on the face of those who promoted the program,” he said.

Katz, of the Legislature’s oversight committee, concurred. An attorney by trade and the only practicing lawyer in the Senate, he said he understands complicated law issues, but investment banking isn’t his strong suit.

“This (New Markets program) was presented to us as a way of saving this mill and I think most of us trusted there were appropriate safeguards built in to make sure the risk was minimized,” he said. “I’m not casting blame at anyone, but all of us, including myself as a legislator, didn’t really perform terribly well.”

FAME, the agency charged with investing money in the public’s interest, has struggled with ensuring accountability in the New Markets program.

Roney at FAME has singled out one-day loans as an unintended tool that is putting Maine taxpayers on the hook for investments that are not making their way into low-income communities and circumvent the original intent of the program.

While the Legislature created a program with no requirements for how businesses use the investments they receive, Roney tried to build some accountability into the program when he was charged with writing its rules. At the time, he included a sentence that required “substantially all” of the investment is spent in the low-income community – a requirement that is a departure from the federal program.

But it didn’t last.

FAME’s staff used the sentence as a basis to recommend the board reject Advantage Capital’s $24.8 million investment in JSI Store Fixtures in Milo, which included a one-day loan of $15.8 million. But FAME’s board backed down when Advantage Capital threatened to pull its more than $30 million investment from Maine, which included $7 million to Putney Inc., a Portland-based pet pharmaceutical company, and roughly $500,000 to Quoddy Inc., a shoemaker in Lewiston. Advantage’s lawyer, Chris Howard, argued that because the deal would be OK under the federal program, it should be allowed under Maine’s.

Three months later, FAME’s board voted to remove the accountability phrasing that required the investment be “expended” in the low-income community.

Since then, Roney says he has begrudgingly accepted deals featuring one-day loans, hamstrung by precedent and the loss of the accountability rule.

In a memo to the board regarding the recent Farnsworth deal, Roney wrote: “While FAME staff continues to have concerns about whether the one-day loan structure fulfills the intent of the program, given the board’s prior guidance and decisions on such matters, the transaction meets the program requirements, so long as it would meet the federal program requirements.”

GOOD INTENTIONS

While the Maine New Markets tax program reveals a troubling trend that benefits out-of-state banks and financial firms more than Maine taxpayers, supporters point to appropriate and successful uses of the program.

In 2013, a Chinese investment firm announced that it would build a new tissue paper mill in Baileyville that could create 80 new jobs. In Washington County, which has one of the highest unemployment rates in the state, the $120 million St. Croix Tissue project is important to the economic health of the region.

“This investment would not have happened without Maine’s New Markets Capital Investment Program,” wrote Jim Oliver, St. Croix Tissue’s controller, in testimony he submitted to the Legislature’s Labor, Commerce, Research and Economic Development Committee in support of L.D. 297, the bill to expand the state New Markets program by doubling its cap from $250 million to $500 million.

In the St. Croix Tissue deal, the mill’s parent company, International Grand Investment Corp., put $24 million of its own money into the New Markets program to attract an additional $16 million in private capital through the state and federal New Markets programs. CEI Capital Management, Enhanced and U.S. Bank were the CDEs that brokered the deal, which FAME’s board approved in November 2013.

“Overall, the program’s track record is showing that it’s creating positive returns for the General Fund and creating significant jobs in the state,” CEI’s Spies said, referencing the results of an economic impact report CEI Capital Management had commissioned Colgan to complete.

The report showed that nine businesses that have received investments via the New Markets Capital Investment program through December 2014 will create or retain 1,178 jobs by 2017, not counting those lost when Great Northern Paper closed its mill. Over a 10-year period, Maine’s General Fund will receive $1.56 for every $1 of tax credit it lost, according to Colgan’s calculations.

Colgan’s report is based on an assumption that all of the jobs created or retained are attributable to the New Markets investment. But that isn’t the case, for example, with Putney, the pet pharmaceutical company. The company has been growing exponentially in the last few years and now employs 80 people. It recently closed on $16 million of private financing. Yet Colgan counts all 80 jobs as a result of the $7 million New Markets deal.

MORE COMPLEX, LESS ACCOUNTABLE

The federal New Markets Tax Credit program has released $40 billion in tax credits to investors since it was created in 2000. It has also grown more opaque as the deals have grown in complexity, according to an August 2014 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

“Complete and reliable information is a vital component of assessing program effectiveness,” the report says. “While the complexity of the NMTC financial structures makes gathering information a challenge, there are several aspects of these structures where better information would aid in understanding the effectiveness of the program.”

More pointed criticism comes from former U.S. Sen. Tom Coburn, a Republican from Oklahoma, who wrote a report arguing that there’s “little available evidence” to demonstrate that the federal New Markets program is effective.

“This tax credit intended to benefit the poor is instead lining the pockets of the well-off, such as big banks and other private investors that claim more than $1 billion in (New Markets Tax Credits) annually,” which is revenue the U.S. Treasury is not collecting. “Because it is funded by taxing the labor of Americans, NMTC is essentially a reverse Robin Hood scheme paid for with the taxes collected from working Americans to provide pay outs to big banks and corporations in the hope that those it took the money from might benefit.”

The federal program is expected to cost the country $5.1 billion in lost revenue between 2013 and 2017, according to Congress’ taxation committee.

The increasing complexity of the federal program is due in part to the creation of more state-level New Markets programs that are sometimes used in combination with federal New Markets tax credits, according to the report.

Despite the report’s call that the U.S. Treasury introduce more accountability into the program, it concludes that it has likely resulted in investments that would not have happened otherwise.

And that’s the problem facing the Maine program now.

The decision to allow for-profit companies – such as Advantage, Enhanced and Stonehenge – to dictate where such investments are made has opened the program up to predictable exploitation, according to Rubin, the Rutgers professor.

“If you open the program up to folks using it to make money rather than do economic development, they’re going to find many ways to subvert its purpose without breaking the law,” Rubin said.

But she acknowledges there are investments and projects that have benefited from the program and have had a positive impact in their communities.

The irony, she says, is the federal program would likely never have been reauthorized so many times without the lobbying heft the for-profit financing agencies brought to bear in Washington.

“That’s the trade-off.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.