Nestled between Moosehead Lake and Baxter State Park are 44,000 acres of state-owned land where hikers roam Maine’s largest roadless backcountry and fishermen discover that Nahmakanta – Penobscot for “where there are plenty of fish” – still rings true today.

During winter, thousands of snowmobilers cruise daily through Nahmakanta Public Reserved Land via one of the region’s busiest trails. Yet between 2002 and 2012, the state harvested more wood – 131,000 cords – from the forests near Nahmakanta Lake than from any other “public reserved land” in Maine.

In many ways, Nahmakanta Public Reserved Land epitomizes the multiple-use philosophy that has guided Maine’s management of more than a half-million acres of state-owned land for decades. But there is growing debate about whether Gov. Paul LePage wants to tilt that balance more toward timber harvesting and away from outdoor recreation.

The outcome of the political fight over the public reserved lands could have major implications for conservation projects statewide and the future of the popular program that helped protect Nahmakanta plus dozens of other parcels in Maine.

“I don’t think the taxpayers would have bought that land if they knew it was going to be managed the same way as (northern Maine’s) commercial forests, especially now with outdoor recreation’s growing importance” to the regional economy, said Don Hibbs, co-owner of Nahmakanta Lake Camps and a critic of the LePage administration’s plans to increase logging and reorganize the agency that oversees the state’s public reserved lands. “We need this land, at least, to be truly multiple-use.”

STATE: PLAN IMPROVES MANAGEMENT

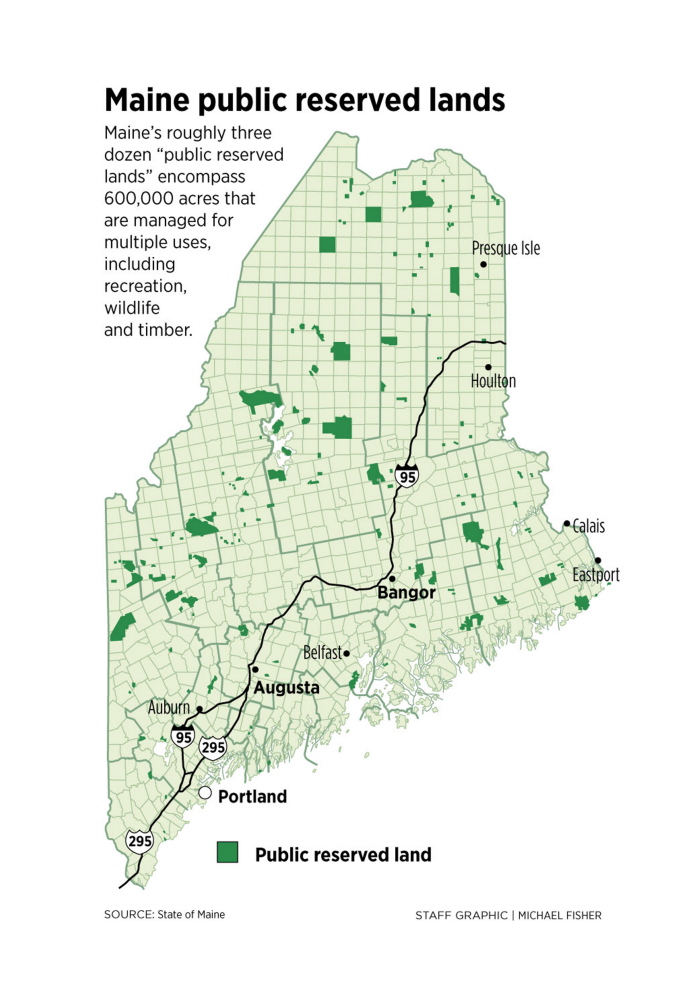

The often-overlooked cousins of Maine’s popular state parks, the roughly 600,000 acres of state-owned “public reserved lands” have been thrust into the political spotlight in Augusta.

Since LePage took office in 2011, timber harvests on state-owned lands have increased by more than 34 percent, from 115,167 cords to 155,152 cords last year, while timber revenues nearly doubled to $7.8 million. The Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands, which manages all activities at both state parks and on public lands, plans to increase the harvest on public reserved lands to 180,000 cords starting next year.

The LePage administration will seek legislative approval in the coming months to use $5 million in revenue from that logging to help Mainers convert their older home furnaces to more efficient heating systems. And to pressure groups into supporting his plan, LePage is holding off selling additional voter-approved bonds needed to complete dozens of land conservation projects through the Land for Maine’s Future, or LMF, program administered by the Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry.

The Nahmakanta lands are among 500,000 acres statewide conserved through LMF since 1987, with most remaining in private ownership.

“The state already has 800,000 acres of public land, but Mainers need help upgrading to more energy-efficient systems that would make it much more affordable to heat their homes,” LePage spokesman Peter Steele said last week.

State officials argue that the governor’s plan will improve management of state-owned lands – potentially improving their value and health – without harming outdoor recreation, wildlife or other “public values.” And all this will happen while helping low-income Mainers keep warm during winter.

“It would be seamless to what is happening on the ground now,” said Doug Denico, director of the Maine Forest Service. “We would be entering the stands (of wood) more often, but we would be doing it in the same way that we did it before.”

Critics of the proposal – who run the gamut from environmentalists to sportsmen and experts in forest management, known in the forestry world as silviculture – accuse the administration of eyeing the well-managed public lands as a piggy bank.

“If you take out all of the silvicultural reasons, which I think are bogus, it comes down to this: It’s really about money,” said Bob Seymour, a professor of forest resources at the University of Maine who frequently takes his forestry students to tour the public reserved lands, which he considers model examples of timber management.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ‘PUBLIC LOTS’

The history of Maine’s public reserved lands – sometimes called “public lots” – predates the creation of the state itself. At the tail end of the Revolutionary War, both the fledgling federal government and the Massachusetts legislature began setting aside acreage within as-yet-undeveloped townships for schools and other “public uses” to encourage settlement.

The public lots transferred to Maine following the state’s separation from Massachusetts in 1820. A century and a half later, the state negotiated with northern Maine’s industrial landowners to consolidate those scattered lots into larger “units” that now comprise many of the state’s public reserved lands.

Today’s tally of public lands includes well-known hiking and camping spots such as the Bold Coast trail in Cutler, Moosehead Lake’s Mount Kineo and Bigelow Preserve in western Maine. But many other lesser-known lands – such as Hancock County’s Donnell Pond and Pineland in New Gloucester – are used primarily by sportsmen and local residents.

“While more than 2 million people visit state parks annually, fewer people know where the more than half a million acres of public reserved lands are located and the outstanding recreational opportunities they provide,” reads a “Your Maine Lands” brochure and map intended to increase use of the lands.

Roughly two-thirds of that land, or just over 400,000 acres, is available for timber harvesting with cuts carried out by private contractors operating under detailed plans prepared by Bureau of Parks and Lands foresters. All of Maine’s public lands are certified as sustainably managed through the world’s two leading certification firms, and state guidelines require forestry to be carried out “in a manner that maintains or improves forest health and diversity, protects special natural features and visitor safety, enhances wildlife habitat, preserves the visual integrity of the landscape and produces a sustainable stream of high quality … timber products.”

AN EFFORT TO SHIFT OVERSIGHT

The amount of wood harvested from state-owned lands roughly doubled from 78,715 cords in 2005 to 155,152 cords in 2014. The bureau plans to thin the amount of “merchantable” timber per acre by 6.5 percent over a 20-year period by harvesting 180,000 cords annually starting in the fiscal year that begins July 1, 2016.

At the same time, LePage’s budget proposed to dissolve the Bureau of Parks and Lands and transfer oversight of the public reserved lots to the Maine Forest Service, which works primarily with the state’s private commercial timberland owners.

Denico, who runs the Maine Forest Service, said that many of Maine’s public lands are actually overstocked with mature trees, which leads to a higher percentage of less-valuable trees as well as higher risks from destructive pests such as the spruce budworm. A 2006 Maine Forest Service survey said the “level of mortality” of trees on public lands was 13 percent higher than the statewide average, although net growth of trees was 18 percent higher.

“You can’t leave something for 40 years and get the results you are after,” Denico said. “You have to go in and do some active management.”

LePage’s plans for managing the public lands hasn’t gone over well with some bureau staff, however.

The previous bureau director, Will Harris, retired last year after nearly four decades with the bureau because he disagreed with the governor’s vision.

“Whenever anybody who is in that kind of position can’t really get behind an administration’s policies, it is time for them to change,” Harris said. “And so it was for me.”

Harris said it didn’t seem that the administration “cared much” about the outdoors or outdoor recreation, and he was frustrated by what he saw as inattention to what he believed should be bureau priorities. One of the biggest concerns, Harris said, was that “once you start down that road of diverting money from Parks and Lands to other things, it gets very easy.”

“We were growing old trees; that is what we do, … and I think people like that,” Harris said. “Parks and Lands is not just about forestry, and I’m sure that is where the administration and I just don’t see eye to eye.”

And LePage may soon be searching for his second bureau director in less than a year after the seat’s current occupant, Tom Morrison, handed in his retirement papers this month. Morrison could not be reached for comment last week.

LePage administration officials insist, however, that the multiple-use mandate for public lands will not change even as more wood leaves the public lots.

“We are not proposing to change the underlying, guiding (principles) with regard to harvesting on public land,” said Walt Whitcomb, commissioner of the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry. “There is a recreation component and a good deal of the land is all recreation.”

GOVERNOR PLAYING HARDBALL

Under current law, all proceeds from timber revenues on public reserved lots pay for all management of state parks and public lands. In fiscal year 2014, the department made $7.8 million from timber harvests – triple the amount from 2005.

The LePage administration is finalizing language of a bill that would divert timber revenues to Efficiency Maine programs that help homeowners purchase more efficient heating systems. The Legislature rejected an identical proposal last year amid concerns about the increased logging and that diverting timber revenues away from the bureau was creating a slippery slope.

So this year, LePage is playing hardball to get that money.

Last week, the administration confirmed that the governor is withholding $11.4 million in voter-approved bonds for the Land for Maine’s Future program. As a result, more than a dozen projects that were approved for LMF funding are now in limbo and will be forced to compete for a much smaller share of money.

It is the second time in two years that LePage has employed bonds that have been approved by voters but not yet sold as a bargaining chip with the Legislature.

The link between LMF and increased harvesting is tenuous and, some say, counterintuitive. Not only do many LMF projects keep land as working forests, many state-owned properties now managed for timber were acquired with LMF funds, program supporters and participants pointed out.

But the funding is now leverage for LePage as he deals with lawmakers and groups opposed to his timber harvesting plans – a connection the governor’s spokesman made clear last week.

“Several of the organizations that are now demanding LMF funding opposed providing Mainers money to keep their homes warm in the cold winter months” last year, Peter Steele said in response to a Press Herald inquiry into the link between the two issues. Steele mentioned the timber harvesting before adding: “Especially after the brutally cold winter we just endured, supporting a proposal to help keep Mainers warm should be a no-brainer for these organizations.”

The strategy infuriated conservation groups that have been negotiating for years with landowners and raised private funds to match the LMF dollars only to encounter a new obstacle months or even weeks before closing the deals.

“We are happy to have conversations about how to keep Maine people warm over the winter, but it shouldn’t be tied to this,” said Jeff Romano with the Maine Coast Heritage Trust, one of the state’s largest conservation groups. “How many more deals are we going to tie to spending this LMF money? We’ve had at least one. If we agree to (increased) timber harvesting, what is the next deal that is going to be part of the mix?”

Send questions/comments to the editors.