DeKALB, Ill. – What do you call an atheist with a wife and two kids?

During the course of their weekly meeting, members of the Northern Illinois University secular student group, Atheists, Agnostics and Free Thinkers, will reveal the punch line to that joke, debate whether religion causes human suffering and consider a Bible study group leader’s invitation to help build houses for the poor.

But first, the introductions:

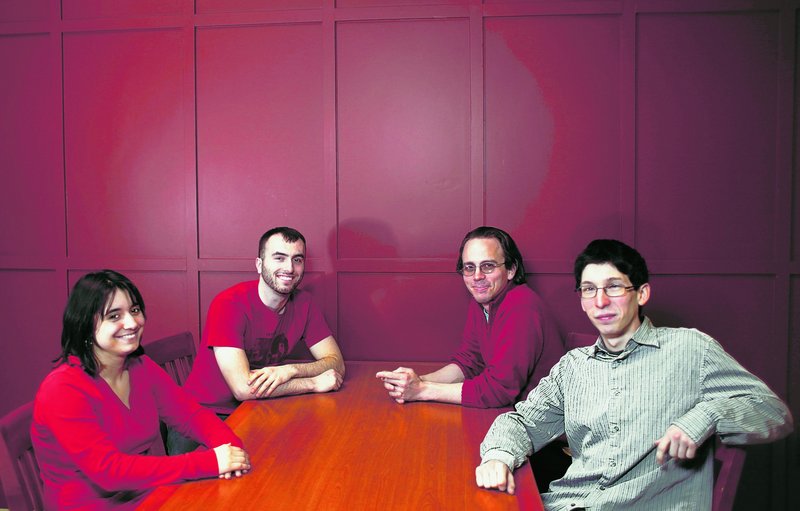

“I’m Brett,” says senior Brett Jacobson. “I’m a triple major in sociology, philosophy and psychology. I’m here because I’m the president.”

“So you have to be!” interrupts junior Haley Whiting, to guffaws. “Way to be a go-getter!”

“I’m an atheist,” says the group’s founder, Katie Panger. “And I’m here because when a man and woman love each other very much …” She pauses, leaving her audience of 14 in suspense for a few seconds before concluding, ever so sweetly:

“The stork comes.”

MORE YOUNG AMERICANS OF ‘NO RELIGION’

Twenty years ago, a sanctioned public meeting of atheists and their allies at a large public university — attended by a friendly Methodist pastor, no less — would have been an extraordinary event.

Even five years ago, it would have been highly unlikely.

But emboldened, in part, by best-selling books such as “The God Delusion” (2006) by Richard Dawkins and “God Is Not Great” (2007) by Christopher Hitchens, young atheists are stepping forward, bonding with their fellow skeptics and reaching out to the religious.

There were at least 195 secular student groups on college campuses in late 2009, up from 42 in 2003, according to the Secular Student Alliance, a nonprofit based in Columbus, Ohio.

“You go to college now — it doesn’t matter where you go — everyone knows someone who’s an atheist, and they know that they’re not bad people,” says Hemant Mehta, chair of the Secular Student Alliance’s board of directors.

Public response has generally ranged from supportive to neutral.

“I think (campus atheism) is a normal aspect of young people inquiring into what’s important, and we shouldn’t just castigate people for doing this,” says Mark Wilhelm, leader of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America’s educational partnership team.

“For those of us who believe that God revealed God’s self in Jesus Christ, we would want to engage them in that conversation.”

Twenty percent of young Americans are atheists, agnostics or have “no religion,” up from 11 percent in 1988, according to a Pew Research Center survey.

And it’s not just society that’s changing; it’s the atheists themselves.

Traditionally, the nation’s nonbelievers have been a contentious lot, sticking it to the nonreligious in the style of Madalyn Murray O’Hair and atheist Rob Sherman of Buffalo Grove, a Chicago suburb, who fires off lawsuits and inflammatory one-liners (“God is make-believe!”) with equal relish.

Not these kids. “We don’t have to face a lot of the (discrimination) older people did, so I don’t think we’re as angry,” says Mehta.

The new atheists are inviting outsiders to their meetings and partnering with evangelicals for service projects. They’re engaging in lively but respectful dialogue with religious groups. They’re launching blogs such as Mehta’s, aptly named “Friendly Atheist.”

LOOKING FOR EVIDENCE BUT FINDING NONE

Who are these 21st-century nonbelievers? What do they want? Why are they rejecting religion?

Panger, the founding member of Northern Illinois University’s AAFT, grew up Catholic. She says she “loved God” as a child and got, if anything, more religious for a while in high school.

But, in retrospect, religion was always an awkward fit.

“It kept me up at night: Is there any evidence for this? Am I just believing a story?” she says.

Her faith was rattled by nonfiction aspects of the novels “The Da Vinci Code” and “Angels & Demons” and shaken by her research into world religions, with their competing claims and dire warnings to nonbelievers.

“After a while, I just couldn’t believe in any of them,” she says.

She drifted away from one close friend during the process and encountered resistance from others.

“Oh, my God! You can’t be thinking that!” she recalls her friends saying. Or, “I’ll pray for you.”

“I didn’t really tell a lot of people because I found every time I told (a friend), the reaction was negative,” Panger says.

Seven states, including North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Texas, have laws on the books restricting atheists from holding public office. A 2007 Gallup poll found that only 45 percent of Americans would vote for an atheist for president; 55 percent said they would vote for a gay person and 92 percent said they would vote for a Jew.

Still, change was in the air in 2006, when Panger entered college. Atheists and other “hidden” minorities were inspired by gay high school and college students, who made great strides in the 1990s and early 2000s by “coming out” and facing stigma directly.

The secular student movement was gaining momentum. And in 2006, Mehta was making a splash in the media by auctioning off his time on eBay, saying he was an open-minded atheist who was willing to attend church — for $10 an hour.

The top bidder at $504 was Jim Henderson, a former evangelical pastor who saw the project as a way for Christians and nonbelievers to learn from each other.

Mehta attended more than a dozen churches and wrote a book based on his experience, “I Sold My Soul on eBay: Viewing Faith through an Atheist’s Eyes.”

Back at NIU, Panger soon discovered that while there were more than a dozen religious groups on campus, there wasn’t one for the nonreligious.

“Why don’t you start one yourself?” her boyfriend asked.

HANDING OUT FLIERS TO STRANGERS

Which is how she found herself standing in the middle of campus on a sunny day in the fall of her sophomore year, handing out fliers to strangers.

Five people showed up for the first meeting of the NIU atheists, held a month later at the campus library.

“Nobody wanted to say, ‘Hey, are you here for the atheist group?’” Panger recalls. “Finally, someone said it, and we were all like, ‘Yeah! Yeah!’“

Three years later, the NIU AAFT chapter is going strong, with weekly meetings attended by 10 to 25 people. There are occasional speakers and service projects, but mostly the students spend the time discussing topics.

A recent meeting began with introductions in which students identified themselves by their names, their years and their majors — math, psychology and philosophy were popular — and briefly stated their beliefs.

Many were atheists, some were agnostics, several were “curious” or “here to get a perspective,” and one, a pastor who attends regularly, was a Methodist.

Members of the group were bemused, as opposed to hostile, when Jacobson said that a friend of his, a Bible study group leader, had invited them to join a Habitat for Humanity project in Texas during spring break.

“Isn’t Habitat for Humanity a Christian organization?” someone wanted to know.

“I’ve done Habitat for two years, and you would never guess the background (of the group),” Jacobson said patiently. “All you do is build a house. It’s a good thing.”

The jokes flowed freely, but if some were irreverent, few seemed angry.

In the case of the atheist joke — “What do you call an atheist with a wife and two kids? A Unitarian.” — the famously tolerant Unitarians were only a secondary target. The joke was on the atheists themselves who, a group member said, tend to gravitate toward houses of worship (but not religion itself) when they have children.

The conversation turned serious after the group watched an episode of the FX reality TV show “30 Days,” in which people with conflicting views live together.

A woman who opposes gay adoption on religious grounds spent a month with a male couple and their adopted children.

The religious woman cried when she was introduced to young adults who grew up in foster care and who would have loved to have been adopted by caring parents, gay or straight. But she didn’t change her mind about adoption by same-sex couples.

In the end, the two sides parted, their mutual opposition firmly intact.

“I found it an extremely depressing episode,” Jacobson said in the discussion that followed. “Especially (when one of the gay men) says, ‘We can’t leave being friends.’ That goes against my entire drive for this group.”

‘GOD IS THE PROBLEM’

Whiting said that, to some extent, she understood the woman’s point of view.

“At the end of the day, she absolutely believes that her eternal soul, her very happiness, her being united in another kingdom with her children and her husband, are on the table.

“Seeing the condition of unadopted children made her cry — she felt for them. You know in your heart that she feels for these children. But she would not say, ‘OK, (gay people) can adopt.’ So God is the problem. That’s my stance. God is the problem.”

“God is just a word,” countered a freshman.

“God is an easy excuse to do all sorts of atrocious things,” Whiting said.

“That’s a very true statement, but I want you to look up Stalin,” the freshman said.

“It was state worship!” a third student said. “They even had a church of Stalin.”

A discussion of human rights violations in Stalin’s Russia and Mao’s China followed.

“So it’s not even a matter of God,” said the freshman. “I just believe humans are inherently evil, once they get enough power to do whatever they want.”

“That could be a discussion for another time,” Whiting observed.

Almost two hours after the group convened, Jacobson seized this opening, wrapped up a few loose ends and adjourned the meeting.

Within 10 minutes, the skeptics had divided into two groups, one of which was heading out for pizza, the other to a local sports bar where, over beer and Sprites, the discussion continued.

Send questions/comments to the editors.