When the subject in school is literature, we don’t give our kids paper and pens and tell them to write a novel. Yet in art class, we often stick brushes in their hands and tell them to paint pictures. Shouldn’t visual education be more than self-expression?

An exhibition organized by the Maine Art Educators Association now at the Saco Museum raises a spate of questions about art education. While the works in the show are of mixed quality, it is unusually interesting.

”Practicing What We Preach: Work by Maine Art Teachers” is akin to an annual members show — it is not juried for quality, though a juror would likely have made a very strong exhibition selecting from the 75 works on view. Of course, juried, it would be a completely different animal — more handsome maybe but far less revealing. ”Practicing” has an honest quality that encourages open and truthful conversation.

”Practicing” doesn’t exude the naive self-consciousness of a student show: There is indeed a handful of very weak paintings, but even these reveal a sense of enjoyment rather than anxious struggle. It might be unusual to see hobby-artists next to dedicated professionals, but it makes sense in this context. It might even make this show better.

What’s more important for a teacher: technical skill or informed enthusiasm? Is it better to have people teaching art who would rather be working full-time as artists or who want to be teachers? What do we expect of art teachers?

One extremely pleasant surprise in ”Practicing” is the vast range of media: painting, photography, sculpture, vessels, raku, cut paper, fiber, installation, prints and much more.

The first piece I saw entering the exhibition (through the fabulously quirky and eccentric Saco Museum) was by Meryl Ruth, who teaches at Deering High School. It’s an incredibly realistic pair of bagels with a box of cream cheese — except it’s a functional ceramic teapot. It’s hilariously wonderful.

The entry hall’s well-lit wall vitrines feature works ranging from colorful fiber to a pair of sculpturally strong raku-fired ceramic masks. Lynda McCann-Olsen’s tiny, enameled and silvered clay vessel is a gem: precious but sculptural and loosely confident. MECA instructor Kelly McConnell’s oil on panel swirls with intoxicatingly exuberant rhythms, from orange to yellow to green and back again.

The museum’s spacious main gallery features a large number of framed works on the walls, which makes the two largest sculptural floor pieces stand out. Most notable is Krisanne Baker’s (Medomak H.S.) ”Saco River Water Column.” The installation comprises 32 Ziplock bags filled with water samples and detritus collected from the Saco River hanging as a rectangular column 12 feet into the air over a pedestal. From a distance it commands the space, while up close you can see algae and organic growth in the swollen sample bags. It is a smart, sophisticated and eminently practical work of art.

Mary Pennington’s handsome ”100 days” is the other bright and approachable floor piece. One-hundred photos mounted on a self-connected aluminum band portray the school days of a pleasantly sparky young girl.

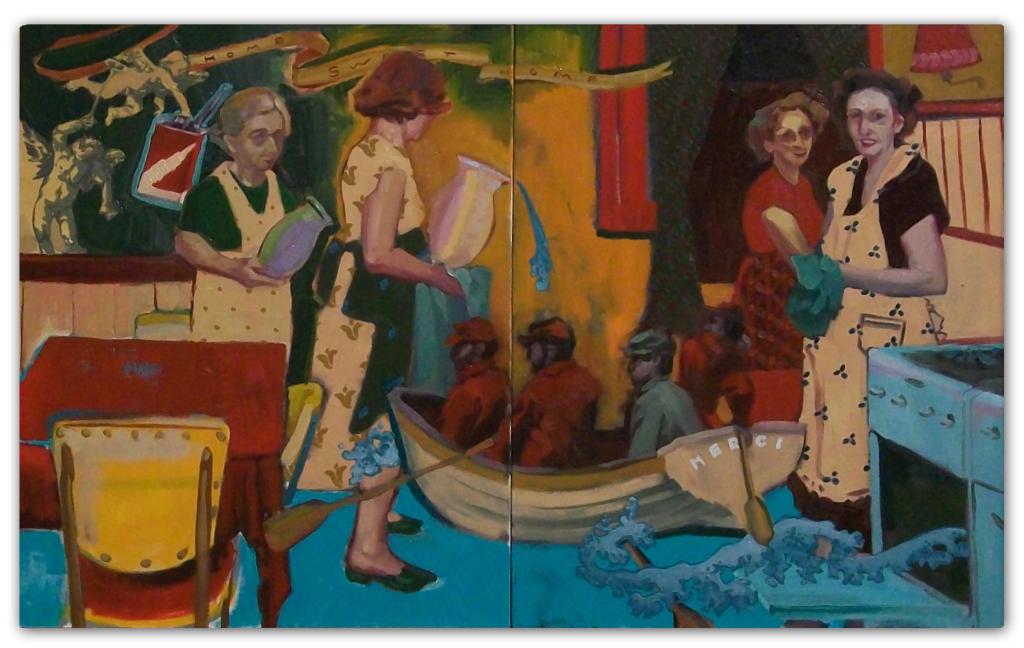

Kevin Goodrich’s ”Water Bearers” is a painting about the disconnect between male soldiers off to war and homemaking wives. Four men in Civil War uniforms sit in a boat, while around them swirl four ’50s-era wives in a retro kitchen. It is a well-handled and complex work of unusual intellectual and painterly accomplishment.

At the show, I met a high school student studying two terrific watercolor paintings — an ancient tree trunk by Linda Murray and an old green truck by Thomas Block. We chatted about how they both looked great from a distance; how the Murray hinted at incredible details; but how the Block revealed more amazing technique close up. Block and Murray are extremely talented artists, but in this case their works played a different educational role. I was impressed.

Just as educators don’t have to draw like Michelangelo to be good teachers, exhibitions don’t have to feature only the strongest works to be interestingly thought-provoking.

What do we expect from art teachers in Maine? Or, for that matter, what do we expect from art? Before responding we should remember that we often learn more from our questions than the answers we receive.

As a meditation on education, ”Practice What You Preach” is deeply instructive.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at: dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.