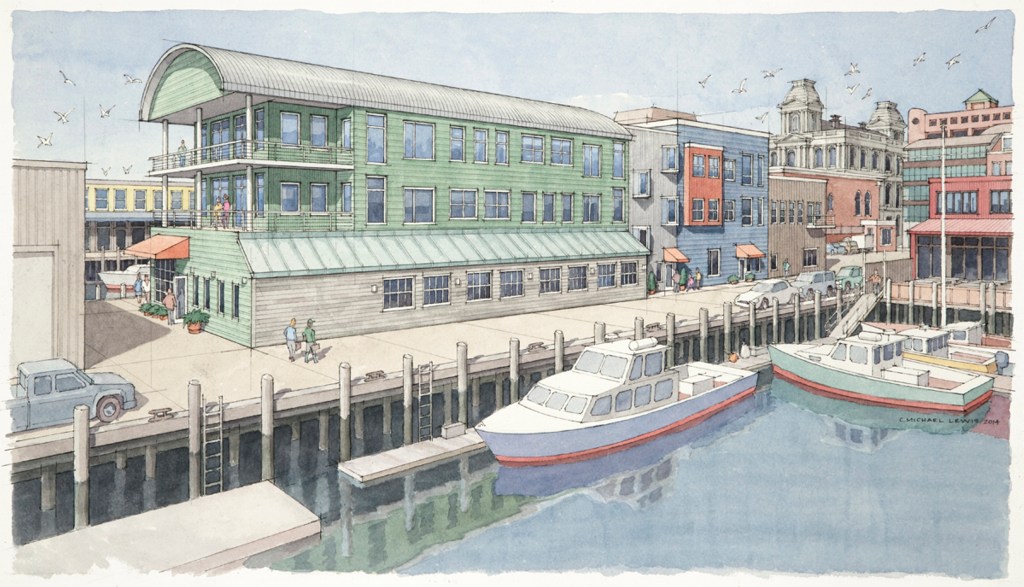

A building rising on Maine Wharf stands out among the surrounding low-lying, weather-beaten structures that for years have housed bait sheds, lobster dealers and other businesses that are right at home on the city’s working waterfront.

The new multi-story contemporary building will soon be home to a ground-floor restaurant operated by a well-known and respected Portland restaurateur. And Wednesday morning, a real estate agent led a group of business people dressed in suits and hard hats around what will become office space on the upper levels, complete with waterfront views.

“It’s exciting to see it come together,” said the wharf’s owner, Stephen Goodrich, a businessman who likes to redevelop unique properties. “I think what we’ve put together is appealing, but also somewhat traditional. I don’t think anyone will look back at this 20 years from now and say, ‘Why the heck did we let those guys do that?’ ”

In many ways, the building symbolizes Portland’s changing waterfront, once the well-protected domain of ground fishermen, lobstermen, warehouses and industrial users. A series of zoning changes in recent years has opened the door to more offices and tourist-based development on the waterfront.

Though some loud, smelly fishing operations have given way to quieter marine-related businesses, the working waterfront is still here. On the nearby Custom House Wharf, for example, men wearing rubber boots and oilskins sorted lobsters and moved large barrels of lobster bait.

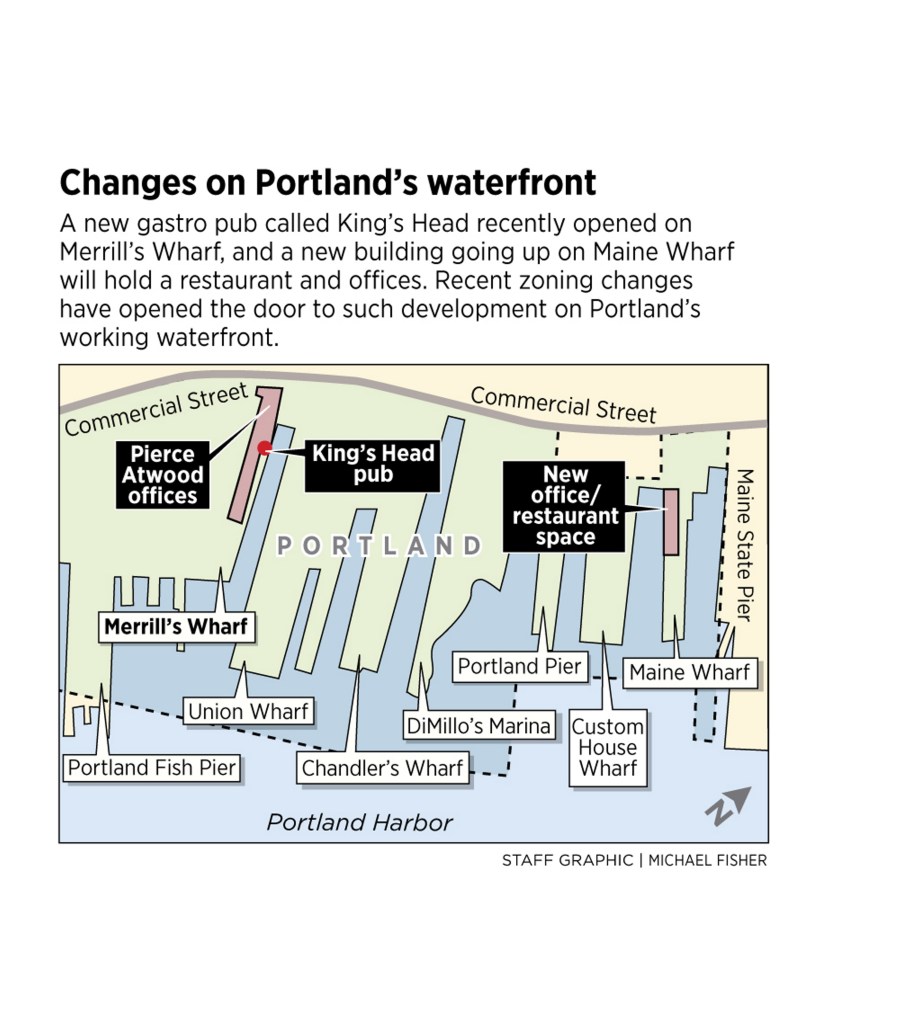

But not far away on Merrill’s Wharf, a gastropub opened in June on the ground floor of an old shipping warehouse that now also houses the offices of a large law firm, while a real estate developer, a cruise-ship office and a communications firm all pass for marine businesses. The city granted permission for the pub only after the space went years without being rented by any marine-dependent businesses.

“Progress is good, when you boil it right down. And development is inevitable,” said Matt McAleney, whose family owns New Meadows Lobster on the nearby Portland Pier and has been a waterfront presence for roughly 150 years.

Gentrification along urban waterfronts that were once the center of industry, rather than playgrounds for tourists, is not unique to Portland. Cities such as Boston and Baltimore converted their waterfronts into tourist destinations years ago.

However, it’s a sensitive issue in Portland, which has a compact half-mile stretch of shorefront that’s suitable to both tourism and industry. The central waterfront includes homes, offices, shops, restaurants and marinas all mixed in with fishing boats, bait dealers, lobster pounds, seafood processors, and marine repair and supply businesses.

The balance of development on the Portland waterfront has been a controversial issue ever since residential condominiums were built on Chandler’s Wharf in the 1980s.

The development prompted a citywide vote that prohibited non-marine uses on the first level of wharves in the Waterfront Central Zone, which stretches from, but does not include, the Maine State Pier to the International Marine Terminal. The effort also led to a prohibition on residential condos that is still in effect.

In 2010, the City Council loosened those restrictions in an effort to allow pier owners to generate the revenue they need to maintain them, while also protecting the working waterfront. The change allows for up to 45 percent of the ground floor to house non-marine tenants, but only after the space is unsuccessfully marketed to marine businesses for at least 60 days at a reasonable rate.

The new rules were endorsed by pier owners and fishermen alike, who worked for several months to reach a compromise. The planned restaurant on Maine Wharf became possible this week after the owner demonstrated that he tried and failed to find a marine tenant and the city awarded him a hardship waiver.

Goodrich, president of the National Payment Card Association and the former CEO of PowerPay, bought Maine Wharf in 2013 for $2.1 million. He estimated that he has already invested twice that amount into renovating the pier, which was so dilapidated that a lobster dealer had to be evicted out of fear the pier would collapse.

Goodrich expects the building, which could see an investment of $7 million or more, to be finished by the middle of next year.

He said Dana Street, the restaurateur who owns Fore Street and Street & Co., plans to open a seafood restaurant on the pier, which also houses Fog’s Boat Works, Bangs Island Mussels, Morrison’s Maine Course and Upstream Trucking.

Street could not be reached to discuss his plans, but Goodrich said the restaurant could open as soon as next March.

That growth and progress can be seen elsewhere on the waterfront.

Next to Maine Wharf, Casco Bay Ferry Lines recently completed a $3.5 million renovation of its passenger terminal.

In the western portion of the central waterfront, the first floor of the recently renovated Merrill’s Wharf at 254 Commercial St. is filling up with marine and non-marine tenants alike, including a restaurant.

The Kings Head gastropub opened on the ground floor of the former Cumberland Cold Storage building, which also now houses the headquarters of the Pierce Atwood law firm. The Kings Head serves creative pub fare, using local ingredients whenever possible, and has 29 high-end beers on tap.

Ricky Binet, who co-owns the pub with Justin O’Connor, said the spot is popular with locals, since it has yet to be discovered by many tourists. “If we get tourists down here, they’re lost,” Binet said.

The King’s Head joins other non-marine businesses – Stillwater Yoga, Federle Mahoney and Down East Enterprises. But the building is also attracting “marine-related” businesses, said Derek Miller, a real estate broker with CBRE | The Boulos Co.

He said three marine businesses have signed leases for the space: Nova Star Cruise Lines, which has its administrative offices there; Prentice Organization, which owns the Chebeague Island Inn and is developing the former Portland Co. complex on the Eastern Waterfront; and Rhumbline Communications. That leaves only two marine-related spaces, he said.

While the new occupants of the piers signal a change in what it means to have a working waterfront in Portland, McAleney, the lobster dealer, is optimistic that lobstermen and other marine businesses will not be forced out by tenants who can afford to pay more for the space.

“Growth is good and progress is good. It’s the only way Portland is going to survive and be a viable port,” McAleney said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.