Time was running out for Indian Township Gov. Bobby Newell.

As his re-election bid approached in the summer of 2006, federal investigators representing four agencies descended on the reservation, inspecting documents dating back to 2002 and asking questions about how the governor had been spending federal funds. The investigation, which had been going on for a year, would land Newell in prison.

“My primary goal on the reservation was addressing and helping people who were poor so that they could have something and deal with substance abuse, and every spare dollar I could get I funneled into that,” Newell says. “I got caught in the political crossfire by ambitious people who wanted to be leaders on the reservation and knew that even if I lost an election … I would be elected governor again.”

“They wanted to get rid of me,” he adds. “I’m the new Don Gellers,” a reference to the tribe’s one-time attorney, who was run out of the country on a minor marijuana charge.

In September, Newell lost his re-election bid to challenger William “Billy” Nicholas, a council member and chief tribal game warden, by a vote of 258-144.

The new administration reported in January 2007 that Newell had left Indian Township $3 million in debt, and had already spent $1.2 million in revenues for the next fiscal year. Tribal government employees had lost their medical and workers’ compensation insurance, both of which had been terminated because of non-payment.

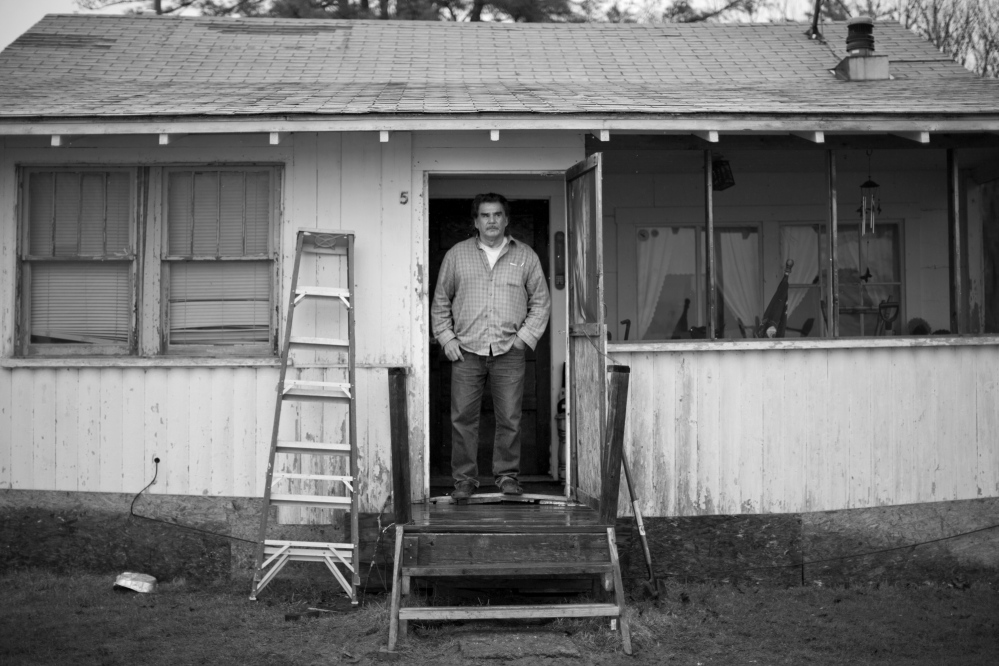

“I just want to go into my little hole and stay there, and if people are going to come and drag me out of that hole, then I am going to respond accordingly,” Newell told a reporter at the time. “If it has to be litigation, then I will do that.”

T

he federal government dragged Newell out of his hole, indicting him on March 20, 2008, on 30 charges relating to the alleged diversion of $1.7 million in federal funds.

Prosecutors alleged Newell had attempted to hide irregularities by firing employees who protested what was happening, including the five terminated after the 2005 protest against his governorship. Ironically, the firing and the lawsuit that followed – and ultimately was settled out of court – is what apparently first drew the attention of federal investigators.

At trial, investigators showed how Newell had used his nearly unchecked power to dole out hundreds of thousands of dollars in “general assistance” payments to friends, family, political supporters and other tribal members. During the last two fiscal years he was governor, the general assistance budget – which Newell allegedly used to grease the wheels of politics on the reservation of 600 – was overspent by a total of $2 million. He paid out apparently arbitrary “honoraria” to himself, Lt. Gov. Joseph Socobasin and tribal councilors. He directed checks to be issued to himself, his son, and other family members for trips that investigators said had never occurred.

“On other occasions, Newell dipped into Housing Authority funds for wedding donations, unspecified small loans, travel reimbursement for his son, Eric, and ‘general assistance’ for two other tribe members,” a federal court opinion would state. He spent Bureau of Indian Affairs housing funds “on his friends, family, tribal council members and their families, including William Nicholas, the tribe’s current governor.”

To cover these costs, Newell ordered subordinates to “loan” the tribal government federal funds granted to support programs at the health, environment and police departments. In the fall of 2005, federal officials started asking where the missing money was but were rebuffed by the governor. By spring 2006 the situation was so dire that Newell was able to meet payroll only by raiding his employees’ 401(k) accounts and not paying federal and state withholding or rent payments (for employees living in federal housing).

“When Newell left office in September (2006), after losing the election to William Nicholas, the tribe only had enough money to pay for one person’s salary – Newell’s,” an appeals court judge would write.

In November 2008, Newell was convicted of 29 counts including conspiring to defraud the United States, misapplication of federal funds, and fraud and lying to federal agencies. He was sentenced to five years at a federal prison in Pennsylvania.

Newell tried to appeal, arguing that these were all “internal tribal matters” under the Maine Settlement Act and therefore not under the jurisdiction of the federal court. The federal appeals judge was not impressed and upheld the convictions. Newell spent nearly four years in prison.

“The judge said I was helping my friends, but I helped everybody,” Newell says, and besides, those who succeeded him were aware of everything he was doing. “I don’t endorse the checks; the council does. But I’m the one who got charged.”

The court judgments did note that Newell did not appear to have acted in order to enrich himself, and several tribal members told the Press Herald they thought his motives may have been benign, if misguided. “Bobby had a very, very kind heart, and if he gave out $100,000, $99,000 of that went to the public and the other $1,000 probably was not accounted for,” says Clayton Cleaves, the current chief at Pleasant Point and a longtime friend of the disgraced governor. “All those people who got new tires and clothes, shelter, oil, cars, and assistance – in my opinion those folks should have come forward, and if they had, I think his (prison) term would have been shorter.”

As Newell’s prison van rolled up to U.S. Penitentiary Canaan in Waymart, Pennsylvania, the Passamaquoddy still had no constitution, and Billy Nicholas was well into his reign as governor.

The tribe’s problems were far from over.

Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Coming tomorrow:

The beneficiaries of Newell’s downfall

Send questions/comments to the editors.