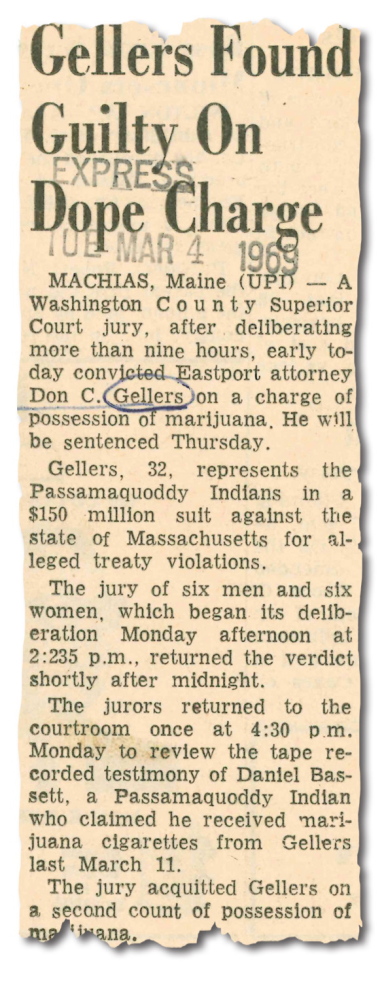

Don Gellers tried to appeal his conviction but was turned down on a technicality.

Based on new evidence that he was being persecuted for political reasons, the Passamaquoddy’s lawyer sought a new trial on the charges that he had six marijuana cigarettes in his house. But as the motion was being prepared in the fall of 1970, his attorney died, greatly hobbling the effort.

Destitute, Gellers turned to his former intern, Tom Tureen, who had returned to eastern Washington County as an attorney for Pine Tree Legal Assistance, a nonprofit that provided free legal representation to poor people.

Tureen, 25, had fallen in love with the area during his internship with Gellers in the summer of 1967. He and his future wife, Susan Albright, had lived in Gellers’ wife’s empty painting studio on one of the headlands looking over the sea. The Beatles’ recently released album, “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” was spinning on the turntable. At a time when many white Americans assumed there weren’t any Indians left on the East Coast, Tureen found himself among a people who not only retained their language but, in some pockets, didn’t speak English at all.

“It was very remote, the setting was dramatic, and the wrongs against the tribe were so obvious,” Tureen recalls. “I had gone up there thinking it wouldn’t be anything more than a summer internship, but the pull was so strong I ended up spending 35 years working with them. … It was a transformative experience for me.”

Afterward, Tureen returned to George Washington University Law School. He graduated in June 1969 and, with the encouragement of former Indian Township Gov. John Stevens, moved to Calais to work for Pine Tree Legal. He soon became interested in Gellers’ land claims case, which had stalled while his former boss tried to fight his pot-bust convictions.

By the time Gellers reached out to him in desperation, Tureen was beginning to dig into the case, informed by his knowledge of the treaties and documents Gellers had painstakingly assembled over the previous five years. He started developing an alternative theory of the land claims case.

Gellers and Tureen put together the first new trial motion, based on Boston attorney Harvey Silverglate’s claim that an assistant attorney general had admitted that his office was involved in a setup that resulted in the drug charges against Gellers, and on new testimony from tribal members.

Tureen’s signed appeal to the court praised Gellers as “the lone legal champion of the civil rights of the state’s most persecuted minority, the Indians” and said his representation of them had “aroused the displeasure of the Attorney General’s Office,” which had sought to prevent his land claims lawsuit “from ever being heard in court, and to stop the defendant from giving further legal assistance to the Indians.” The AG’s office had “subjected the defendant to terroristic measures never employed on anyone else in order to elicit him to get marijuana” including sending a two-man team to intimidate him with the suggestion of violence.

It had all been done, Tureen wrote, “solely out of malicious political motive.”

But according to Gellers and another attorney, Tureen suddenly abandoned his client just hours before the crucial hearing for a new trial at the appeals court in Ellsworth. (Tureen says he doesn’t recall this happening.)

Philadelphia attorney Hy Mayerson says he was in the room when it happened. He had been sent to Maine by the National Lawyers Guild, which was extremely concerned about the way the state was handling the criminal case, to express their reservations through an amicus curiae or “friend of the court” brief.

Tureen, as Mayerson and Gellers both recall, was detached during the meeting, his attention focused on a law review article he was preparing on his new theory on the land claims. They said he would occasionally ask Gellers some question about the treaties. “He wasn’t representing his client. He was withdrawing and paying no attention to the momentous hearing that was taking place the next day,” recalls Mayerson, now a prominent class-action attorney in Pennsylvania. “He said, ‘You take care of it, Mayerson!'”

“I thought I was going up to represent the National Lawyers Guild in its strategic position – that even if the marijuana had belonged to Gellers, it had no harmful effect – and suddenly I find myself defending a lawyer in a criminal hearing because Tureen wouldn’t do it,” he says.

At the hearing the next day, Mayerson wrote in a sworn affidavit, “Tureen whiled away the hours, sitting next to me, proofreading that aforementioned law-review article draft, and not volunteering to say or do anything in the day’s proceedings, for his client.”

Gellers felt completely blindsided: “The betrayal was so sudden and shocking,” he says. “I thought Tom and I were friends. He appeared with me on television, and we had this history of having done so many things together where he was a trusted person.”

Around this time, the embattled attorney was lodging at the home of the now-retired Press Herald reporter William Williamson, who later remembered Gellers’ phone calls to Tureen, in which he pleaded with him to serve as his counsel on his final appeals. “Tureen refused, and Gellers launched into a verbal tirade against his former friend that was beyond anything I have ever heard,” Williamson would later write.

Whether Tureen had simply become consumed and distracted by his land claims research or rather saw advantage in abandoning his former boss’s legal defense is unknown.

Mayerson believes the latter. “It was plotted and diabolical,” he says.

In an interview, Tureen was asked about these episodes, and first said he wasn’t a lawyer yet, so he couldn’t have represented Gellers. When his memory was refreshed with citations from court papers documenting his role and the time frame of the events, he said he didn’t remember the details, but believed his employer, Pine Tree Legal Assistance, had pulled him off the case.

Donald Fontaine, then-president of Pine Tree, said that may have been so, as there had been a change in policy around that time by the program’s funder, the federal Office of Economic Opportunity, forbidding its lawyers from handling criminal cases. “It wouldn’t have had anything to do with the fact it was Gellers,” he said. “We would have been delighted to represent him, but I suspect that was probably the scenario.”

Regardless, Tureen’s sudden withdrawal left Gellers without proper legal representation, forcing him to cross-examine witnesses himself. It may not have mattered, however, as Judge William S. Silsby – the same judge who had earlier found him guilty – appeared dead set against his case. The state once again was represented by Assistant Attorney General Richard Cohen.

Silsby refused to let the Passamaquoddy Anthony “Pluto” Stanley testify to anything concerning the vandalism episode he witnessed involving Gellers’ car and state police Detective W. Lawrence Hall’s alleged intervention to prevent charges from being filed in the incident. Gellers wanted to introduce these incidents as evidence of a conspiracy, with the state authorities allegedly willing to cover up an informant’s crimes while the attorney was fighting for his freedom. According to Gellers, the judge also refused to let Stanley testify that Danny Bassett – who by then had killed Indian Constable Percy Moore – had told him that he intended to kill Gellers as well.

Gellers says former tribal Gov. George Francis came to testify that Bassett had beaten his wife, Annabelle, to the point where she needed hospitalization, and that Bassett had told him he had framed Gellers and gotten away with murder as the payoff. Francis was not allowed to testify.

John Sockabasin came to testify that Bassett and Hall had plied him with liquor on the reservation to get him to lead them into Gellers’ home without permission while the young attorney was in Boston filing the Indians’ potentially epic land claims lawsuit. Again, Judge Silsby refused to allow him to take the stand.

Gellers wasn’t allowed to ask Hall who had dispatched him to investigate the vandalism of the attorney’s car, or to ask Assistant Attorney General John Kelly if it was true they had discretion to prosecute marijuana as a misdemeanor. “Immaterial,” Silsby said in each case.

Bizarrely, Silsby refused to allow either the National Lawyers Guild or the American Civil Liberties Union to appear before him as friends of the court in the case, saying they lacked “legitimate interests.”

Silsby rejected Gellers’ motion for a new trial early the following month, May 1971.

According to Gellers, he met with Assistant Attorney General Cohen a few days later and informed him he planned to emigrate to Israel, though he intended to continue to assist in the prosecution of his land claims case. Cohen, he says, did not object and was provided his address.

He continued to fight his conviction for another two years, appealing to Maine’s highest forum, the Maine Supreme Judicial Court. His final appeal was rejected on Feb. 20, 1973.

Few in Maine would ever hear from him again.

Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Coming tomorrow:

Tom Tureen takes the lead

Send questions/comments to the editors.