SAINT CROIX ISLAND — It was here, on a tiny island near the mouth of the St. Croix River, just south of Calais, that Europeans first tried to plant a settlement in what is now New England.

None of them would have survived had it not been for the Passamaquoddy.

The party was French, and they settled here in the spring of 1604, four years before the abortive English colonization attempt at Popham Beach and 16 before the Mayflower voyage. Their 79-man party – which included Samuel de Champlain, who would later found Quebec – believed the six-acre island would provide protection from the Indians while affording easy access to the hunting and crop-growing grounds on the mainland.

Like many who tried to colonize these parts, the French underestimated the conditions in eastern Maine. The river froze, preventing the use of boats, and the powerful tides tore up the ice, making it unsafe to walk across. Shivering in inadequate shelters on their tiny island, the isolated French began to starve.

Then the Passamaquoddy came, took pity, and gave them a cache of fresh meat and medicinal plants. Half the colonists survived the winter to flee southeast across the Bay of Fundy to what is now Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. “It would be very difficult to ascertain the character of this region without spending a winter in it,” Champlain concluded.

The Passamaquoddy knew the region well. Their ancestors were living in Maine 13,000 years ago, when the Ice Age ended and melting glaciers revealed vast tundra, a stark landscape of sedges, dwarf pines and grasses frequented by herds of caribou and mastodons. Their forefathers had adapted with the changing environment as tundra gave way to forest, mastodon to moose, caribou to deer. Later, when the glacial melt flooded an island at the mouth of the Gulf of Maine – now Georges Bank – the great tide-driven gyre kicked into life, creating one of the most fecund marine environments in the world.

Fish and game would sustain the Passamaquoddy right up until outsiders took much of their land and fishing grounds.

By the time European explorers arrived on their shores, southern Maine Wabanaki had sprawling fields of corn, which were remarked upon by Champlain and, later, John Smith. But the climate was harsher in eastern Maine, the soils thinner, and the Passamaquoddy sustained themselves by hunting and fishing. Pierre Biard, a French Jesuit missionary who lived with the Passamaquoddy from 1611 to 1614, said they got their food from “chase and from fishing, for they do not till the soil at all” and described their seasonal round: hunting for inland game in late fall and late winter, feasting on spawning fish in the early spring, on inshore cod in May, and spawning eels thereafter.

Glooscap, the creator, according to Wabanaki lore, was an immortal hero who used his powers to improve and transform the world. Glooscap confronted selfish creatures that trampled on the well-being of others and taught that power should be used only for socially constructive purposes. He is said to have left his people just before Champlain’s arrival, leaving them to face their greatest challenge alone.

Relatively remote from the centers of European settlement, the Passamaquoddy were able to better survive the horrific disease epidemics that decimated New England’s Indian tribes following European contact and the terrible series of Anglo-Indian wars that extinguished many tribes in the Colonial era.

They also had the relatively good fortune to have their lands claimed by the King of France, which held the eastern half of Maine and what are now the Maritime provinces until 1763. While Massachusetts Puritans looked upon Indians as savage heathens, the French regarded them as allies, their chiefs as vassal lords.

“We developed a good relationship,” says tribal historian Donald Soctomah. “It wasn’t perfect – there were a few items where there were some misunderstandings – but they came to be more allies with the tribe.” Jesuit priests converted many to Catholicism, and until the end of the 19th century, French – not English – was the most common second language in the tribe.

With the French defeat, the Passamaquoddy found themselves within the less hospitable British Empire. When the colonists revolted, they sided with them, responding to a call from George Washington himself who wrote asking their help in protecting the Eastern Frontier. They chose the winning side, of course, but because Nova Scotia (of which New Brunswick was then a part) did not rebel, they found their traditional territory split by a new international boundary. Over the next two centuries, many of the Passamaquoddy in New Brunswick would move west across the St. Croix, though some 200 remain in Canada.

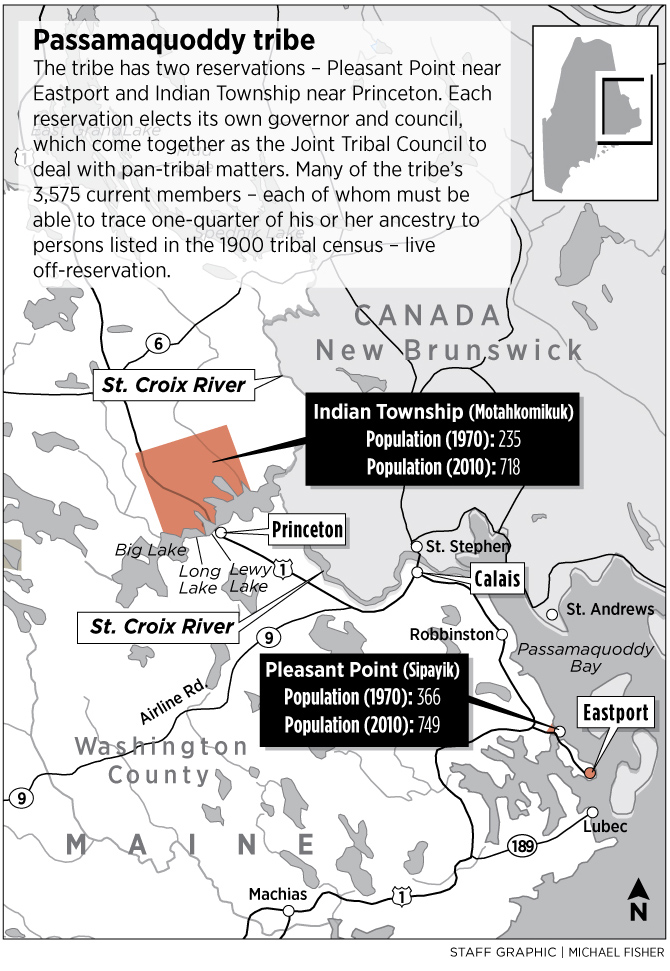

As more English colonists arrived Down East in the 1790s, Massachusetts (of which Maine was then a part) negotiated a treaty by which the tribe agreed to surrender most of its land in exchange for unimpeded fishing rights on the St. Croix, a trust fund, and what are now the reservations at Pleasant Point (near Eastport) and Indian Township (north of Princeton.)

“I think the main hope for the tribe was that they would be able to survive on the resources,” Soctomah says. “Some were still living a traditional life – fishing on the ocean or hunting at Indian Township. But then Maine started restricting access to these resources.”

By the 1890s, Maine courts had ruled that the Passamaquoddy had no rights to hunt on their own land because the tribe – now lacking the ability to negotiate treaties – no longer existed as a sovereign entity. Soon members of the tribe were forbidden to cut trees, while many of their fisheries resources were destroyed by dams, overfishing, and a causeway connecting Pleasant Point to Eastport, which until then had been an island town. Much of the Passamaquoddy land was illegally seized. The tribe’s trust fund was looted by the state.

Amid political, religious, and cultural pressures, the tribe suffered a split in the mid-19th century, with one faction moving to the winter hunting grounds at Indian Township – “Motahkomikuk” in Passamaquoddy – and the other remaining at Pleasant Point, or “Sipayik.” Divisions between the two reservations – which originally included tensions over substituting elected chiefs for hereditary ones and Protestantism for Catholicism – remain to this day. Each has its own governor or chief, government, and council, though the tribe is legally and culturally a single entity.

By the mid-20th century, state Indian agents controlled the rationing and distribution of food, heating fuel, medical care, and, by extension, much of tribal life. Fifty years ago today, Indians had no right to vote in Maine elections, nor could they serve on a local jury. When one of them was murdered, nobody was held accountable.

And then, one day in May of 1964, a group of Passamaquoddy decided they’d had enough.

This is their story.

Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.