CAMDEN – The boxer Baron, standing alert and upright, answers the doorbell with a bark.

The dog’s master, Robert Manns, follows closely behind with a good-natured bark of his own.

“We usually think of New York as very quick,” says the aged and witty playwright, explaining why it’s taken America’s theater capital so long to catch up with his work. “But in fact, it’s very slow. For years, agents have been telling me ‘No.’ “

The rejections that Manns has collected stem from his unwavering insistence on writing plays in poetic metered verse and featuring high-profile historic characters. At times, he has felt that he’s tilting at windmills.

But those windmills are starting to fall.

After having one of his plays produced in New York more than a half-century ago, Manns returned to the Big Apple this summer with a production of “Yorktown” at the Abingdon Theatre, an off-Broadway house on West 36th Street. “Yorktown” is a piece of historical fiction set during the 1781 Revolutionary War battle. It features as central characters Gen. George Washington and his trusted right-hand military men, Henry Knox and Nathanael Greene.

“For the past 70 or 80 years, poetry has been a no-no on Broadway and off-Broadway. Verboten. Plays about national people in the past or people who have gained national attention in the past are also a no-no,” Manns says.

“Those two no-nos I have taken up as the cause, because when you omit them from theater, you omit two of the most powerful agents you can put into it: verse and big people.”

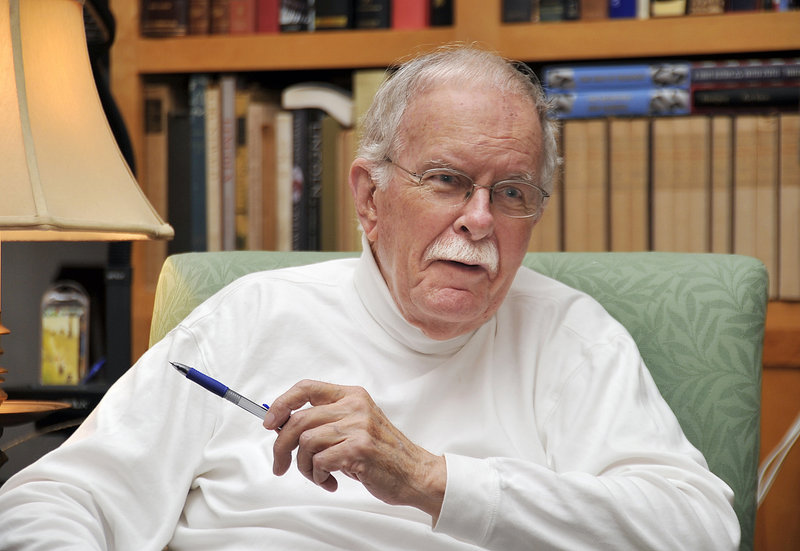

Manns, 82, ushers his visitors into a sprawling sitting room lined with bookshelves stuffed to overflowing. Oversized windows look out onto the quiet forest behind the modern house. It’s a gray November day, and Manns and his wife, Didi, are content to stay inside and watch the ever-entertaining parade of birds and wildlife that passes beyond the glass.

A former regional representative of the National Audubon Society, Manns is best known for his environmentalism and dedication to birding. In his professional life before he retired to Camden from Georgia, Manns pioneered the development of advanced optics for birders.

But he has long fostered a passion for theater. He wrote his first play at age 19, and in the 60-plus years since, has pecked away on the typewriter — the computer is also verboten in his world — and produced script after script. Manns has published 15 full-length plays and more than 30 one-acts.

His work has been produced across the United States. But New York has proven elusive.

THE MOVE TO MANHATTAN

Manns lived in Manhattan for several years in the mid-1950s, arriving from his Michigan home with finished plays in hand and cavorting with theater heavyweights Alan Schneider, a famous director (“Waiting for Godot,” “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”), and Lucille Lortel, an influential actress and producer (“The Man Who Laughed Last”). For a time, he even had the ear of Audrey Wood, the agent for Tennessee Williams.

But his success as a playwright was never enough to sustain a career in theater, and Manns went to work in other fields to earn his living. He was selling audio equipment in Manhattan when he met Schneider, who was then the second-most powerful director in America, behind Elia Kazan (“Death of a Salesman,” “A Streetcar Named Desire”).

“I was working as a salesman, and in walked a very short man, who picked out some gear,” Manns said. “We were sitting there filling out the paperwork, and I asked him his name. He said, ‘A. Schneider.’ I asked, ‘Is that Alan Schneider?’ and he said yes. I think my left pant leg went dark.

“I asked if he would mind reading three one-act plays that I had written, related in theme. He said yes, and three days later he walked in swinging the plays over his head and said, ‘Bob, I’ve got a production.’ I think probably my other pant leg went dark.”

The plays — “Pygmalion and Galatea,” “Pitahecanthropus” and “The Orgy” — received their production at Lortel’s White Barn Theater in Westport, Conn. Mann’s New York debut soon followed, and then that was it. Nothing else happened.

Manns kept writing, but failed in his efforts to have more of his work produced in New York. He left the city for Florida in 1960, and followed his career as a salesman. He eventually moved to Georgia, where he spent 30 years.

That’s where he became interested in birds, the environment and binoculars.

But Manns never stopped writing. Many of his plays were produced in Atlanta, where he had an association with the Callenwolde Fine Arts Center, the Atlanta College of Art, the Atlanta Shakespeare Tavern and various other theater and fine-art organizations.

He and Didi moved to Camden a decade ago.

“My wife retired from Georgia State University in Atlanta and said, ‘Would you like to retire to Camden?’ We had been up here several times, and loved it,” he said. “What the South is because of its climate, Maine is because of its habitat. I readily said yes.”

‘RETIRED,’ BUT STILL WRITING

Since moving to Maine, Manns has maintained somewhat of a low profile. A few of his plays have been produced in the midcoast, and he continues to write.

He wrote “Yorktown” in Maine a few years ago. The Drama Garden produced the play in New York, directed by Eric C. Dente.

The director knew Manns through a prior association. He acted in Manns’ “Lincoln in the White House” a few years ago, and the two hit it off as friends.

For “Yorktown,” Manns created a dramatization of the important Revolutionary War battle. The key element of the play is his decision to bring the wives of the generals into the action. The women were not present at the battle site, but Manns includes them under the assumption that the generals were devoutly dedicated to their wives and drew strength from their affection.

In doing so, he introduces the element of family into this important moment in history — and in exercising his dramatic license, he humanizes these generals in ways that other historical fiction has failed to do, Dente said.

“The fact that he took on a subject matter that you do not see on stage, based on a piece of American history that was so important to our current existence, and that he introduced the role of family into these men’s lives, was pretty impressive to me,” he said. “I was thrilled with the play, and I enjoyed the material.”

Dente credits Manns for his courage and commitment to writing in verse. Not many playwrights use that technique. It’s bold and risky, and no doubt accounts for Manns’ struggle to see more of his work produced.

But it’s powerful writing full of impact.

“It’s just a very elegant and romantic form of drama. And I must say, it was very well received. People who are more classically trained and who are tuned to classical things were happy to see a contemporary play written in verse. And the younger audience was thrilled by the fact that it was still alive and active,” Dente said.

Manns’ friend and fellow Camden resident J. Brian Smith calls him “America’s most accomplished living playwright.”

That’s high praise, but Dente said it’s fair. Given his background and long-ago association with the titans of American theater — however brief — Manns could write an epic tale about his own life, Dente said.

“In many ways, he has lived the American dream when it comes to theater and life,” Dente said. “Where he came from and how he has been able to work his way through difficult circumstances, it’s powerful stuff.

“It’s the great American theater story.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.