“Drawing: Marks, Traces & Imprints” now on view at the University of Maine-Augusta is the most handsome show I have seen at UMA’s Danforth Gallery — and the quality of the works lives up to the installation.

The curators of “Drawing” (MECA illustration department chairman Alex Rheault and Danforth Gallery director Karen Adrienne) visited many studios over the summer with open eyes rather than a predetermined polemic. Their intuitive approach paid off with an excellent exhibition of drawing-based works by 10 Maine artists.

We have recently seen works by many of them: Larry Hayden’s “continuous drawing” work has been at June Fitzpatrick; Stephen Burt has works at UNE; Lucinda Bliss, Lisa Pixley and Yeshe Parks have been shown this year at Whitney Art Works; and I juried Jo?LeVasseur into “Black and White” at River Arts earlier this year.

What I like most about this show is its combination of range and quality — though a few artists do stand out for me.

Pixley’s two engravings get backup from her excellent charcoal drawing of a porcupine seen from behind. The marks, rhythms and composition all sing in chorus of his spiky boldness.

The engravings are notable as much for their quirk as their technique. One shows a pheasant, brilliantly rendered and colored, that breaks down on closer inspection. For all its detail, it has no head or wings, so it leaves you with unexpected questions. The wit is uncanny.

Pixley’s ax has a similar effect: for all its mark-making and tonal virtuosity, the head of the otherwise plain ax is covered with decorative scrawls and the word “FIN” (French for “The End”). It’s hard not to conclude this might be the favorite tool of a murderer.

This show offers much to like. Bliss’s tree covered in green velvet is draped with yards of strung green beads, whose linear interplay is beautiful. And though the plastic sheet looming above pretends — badly — to be a cloud, it has the clear effect of turning the piece from a monolithic sculpture into an exquisite installation.

Ling-Wen Tsai’s smartly jaunty aluminum squares are partially painted with linear grids and exuberant rectangles that pulse with dancing organic rhythms.

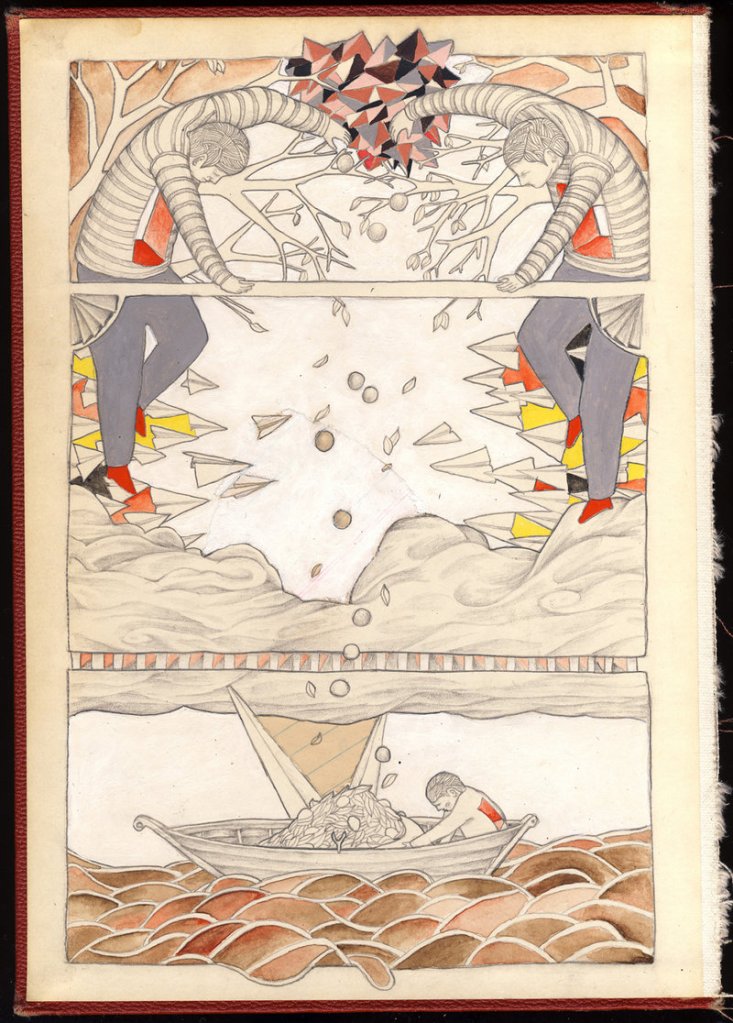

Parks’ tight little scenes are like tiny triptychs with strange and complex narratives. They are oddly human despite their surreal language.

Andrea Sulzer’s small collages jangle brightly between the logic of landscape and still life. Their visual wit is pressed further by Sulzer’s larger drawings of a dunce cap and a piece of hard candy on a white, textured page. She reminds us that fun and desire can be more complex than we admit, though sometimes simpler than we realize.

This excellent exhibition underscores the widely varying roles of drawing in Maine art. It is particularly accessible because it doesn’t try to define or limit the idea of drawing. It doesn’t lecture — it illustrates.

Alex Rheault’s small exhibition of her own drawings opened on Friday at Art House in Portland. Her charcoal life drawings on gessoed panels bristle with sexuality. Each features multiple and often fractured images of a single female model. Rheault not only has a great eye, but a strong hand. She can draw.

My favorite is “beautiful crisis.” In the upper right, we see the model’s face. On the left, she is prostrate with her face down (similar in style and pose to Egon Schiele’s “Forward Bent”). In the lower right, the model — barely dressed in panties, bra and heels — lies on her back with her garter-stockinged legs spread wide.

The drawing ebbs and flows oddly because the element that, by size, should be closest is rendered most lightly, while the most prominent should be the farthest away due to its scale. And it works.

Rheault’s mark-making delivers some tremendous passages (particularly the feet, buttocks and crotch). There is no other way to say it: this is a steamy drawing. Yet it feels neither awkward nor confrontational, because the sexuality seems that of a confident and mature woman.

“Collapsing, being” is similar, and soars on some particularly strong passages in the doubled-image of the model. In this work, Rheault posits several brilliant pairings of positive and negative forms in addition to her wonderful sense of body gesture: she pairs the shape of the right breast above the bra against the stump of the right arm (cut off by an absent article of clothing we fill in ourselves).

As well, the relationship between the shape created by the outside of the legs and their internal space is virtuoso not just in mark and metaphor, but form.

While Rheault’s larger works are a bit jumbled and less taut in comparison, they came earlier in this series. Considering the strength of the progress, I am looking forward to what she does next.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.