During times of national economic erosion, arts nonprofits tend to be like canaries in a coal mine. Yet over the past few years, the Harlow Gallery — founded as a community artists cooperative in the 1950s — has consistently stepped up and forward in the quality of its programming and presentation.

The Harlow’s “One of a Kind” is a handsome show of about 50 framed monotypes and monoprints by six Maine artists. It is interesting and enjoyable for the professional, the practitioner and the public.

A monotype is an unrepeatable print made from a plate inked or painted without any repeatable matrix. A monoprint might also be run through a press, but it uses at least one repeatable element.

I was drawn to works by all of the artists and found few that I disliked. My favorite pieces were by Margo Ogden, a retired art educator who was a founding member of Praxis, an artist-run gallery in Freeport.

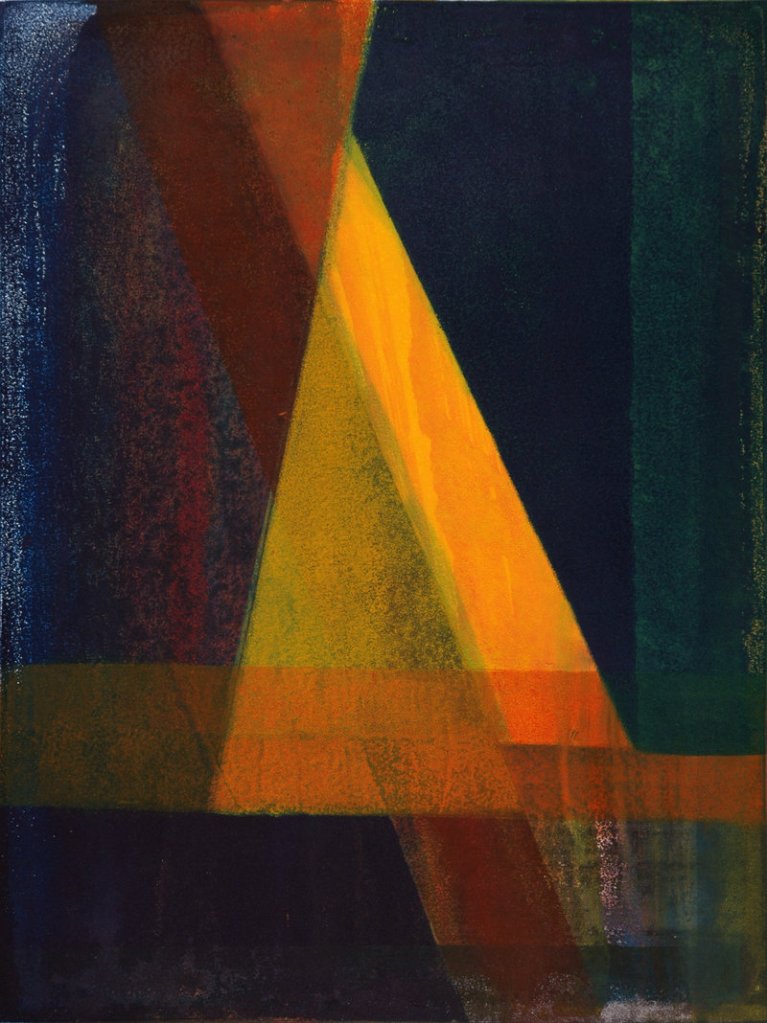

Her “Angle of Tranquility” is a deeply layered and saturated geometrical abstraction based on an apparent yellow triangle on a field of dark blues and greens. Yet there is no lower right corner to the triangle: as your eye follows the subtle bands of color through the composition to parse the logic of the form, rather than resolving, the ostensibly simple composition unfurls. It is a stunning piece that turns on a hidden kernel of brilliance.

Ogden’s “Autumn Tones” reveals her awareness of Diebenkorn’s layered geometrical strategies, and her “Madras” again follows subtle logic — this time of colorfully decorative textiles — and delivers a striking compositional coup by emerging from the left side of the image. It is subtle, attractive and very, very smart.

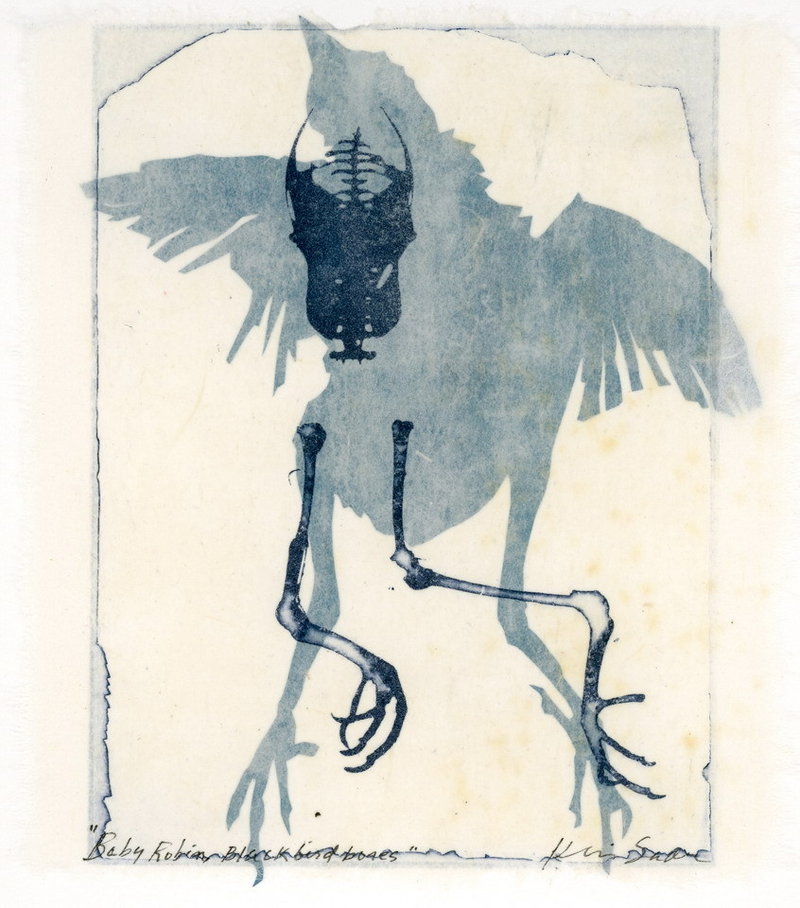

Kris Sader is a printmaker, environmental site-specific artist and printmaking adjunct at UMO. Every one of her eight pieces in the show is thoughtful and exquisite. (Galleries take note: She rocks.) Her “Baby robin, Blackbird bones” is a small piece with at least one transparent print layer laid over another image. It blends a touch of thoughtful sentiment with a wisp of scientific clarity. It is a smartly intellectual piece — but deeply sympathetic.

Sader’s “Thrush at Field’s Pond” is dense and luscious. A maroon bird is presented in full profile over a green-edged aqua ground. White circles provide a flowing and popping effervescence that makes for water rather than sky. It reminds me of the great symbolist, Odilon Redon.

I also liked Robin Brooks’ rhythmic forests — in particular, her use of collage or scratching to introduce horizontal elements to her vertical compositions.

I am split on Corliss Chastain’s two series. The “Burning Bears of Manitoba” feels unpleasantly claustrophobic to me, while I really enjoyed the pleasantly decorative calm of the four works from the “Delkon River Blues” series.

These seem to be landscapes reflected in water; all-over compositions with reflected trees, horizonless due to the vantage of looking down onto water. They are soft, rich and technically masterful. Most impressive, however, is their subtlety and metaphorical depth — they feature torn bits of pages from the Bible used to present the reflections of dimpled water.

The passages reflect time and memory as some sort of shimmering, narrative soup. They could be reflecting how many of us understand the Bible (or memory in general) as suspended passages. They could be reflecting how our culture is one of flow and reflection. I have always been squeamish about “altered books,” but these pieces are wholly free of anxiety or even a single angry edge.

The focus on the medium — monotype — holds “One of a Kind” together with visual coherency, but the content of the work and the calm confidence of all the artists give it the feel of a thoughtfully curated exhibition. It is a very good show.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.