PORTLAND — John Marin loved Maine for many reasons. The architecture of the built-up villages along the coast thrilled him. The rugged, unruly sea captivated his imagination. The language of the fishermen tickled his ears.

But the sunsets were something else altogether. They held Marin’s imagination as little else could. He told his New York art dealer, Alfred Stieglitz, that the Maine sunsets were made to order, “the kind no artist can paint.”

Marin got it. He understood Maine better than most of the artists who came before him, and those who have come after have spent better than half a century trying to find the secrets that he held close.

This summer, the Portland Museum of Art offers an exhibition that begins to hint at Marin’s uncanny relationship with Maine. “John Marin: Modernism at Midcentury” presents the first museum-scale Marin exhibition in 20 years and the first comprehensive examination of the latter phase of his life and career.

The Portland show focuses exclusively on Marin’s artistic production from the 1930s to the end of his life in 1953. Not coincidentally, that roughly 20-year period corresponds precisely with the time Marin settled down at Cape Split on the far Down East coast of Maine. Previously, he had been an itinerant Maine painter, showing up each summer with his wife and young son from their home in New Jersey and staying in different spots along the coast.

Marin wandered about from Cape Small at the eastern edge of Casco Bay on up to Stonington. But in the early 1930s, he bought a home at Cape Split on Pleasant Bay and began spending half the year in a single place.

Maine not only gave Marin his artistic voice, but the transient quality of the natural world — most notably, the insistent sea — changed him and his painterly instincts. In this exhibition, Boston-based guest curator Debra Bricker Balken demonstrates how Marin’s time at Cape Split influenced his work, and how his embrace of modernist sensibilities served as a precursor to the abstract expressionist ideas of Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock and others.

Working in a remote part of the world and largely out of communication beyond a flurry of letters to and from New York, Marin developed a modern visual language that focused on landscape and place at a time when much of the art world was preoccupied with abstraction, Balken said.

“He is as much a cousin of Winslow Homer as Jackson Pollock, and that is the point of this show,” said Thomas Denenberg, the museum’s chief curator.

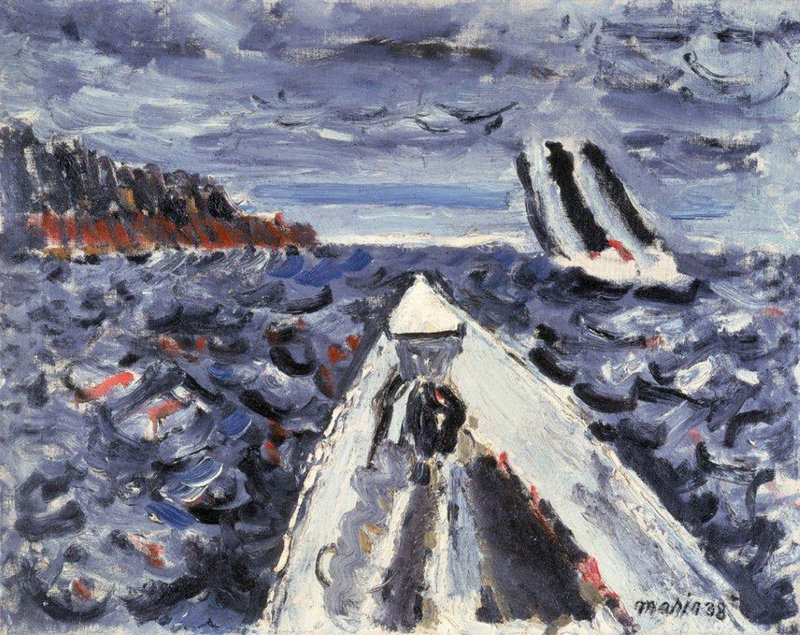

No painting in this exhibition better details Marin’s place in the larger art world than the showpiece, a dense oil-on-canvas painting called “Lobster Boat” from 1938. Marin presents the bow of a boat — no details beyond the inverted “V” jutting up from the bottom of the frame — cutting through the choppy sea, which is represented by a repeating series of squiggly lines. He portrays an island with straight, short brush strokes and a vessel under sail with slightly angled lines.

Interestingly, Marin chooses to represent the sail with black lines and the hull of the boat with a blob of white. With the exception of one solid blue line along the mid-horizon, his sky is punctuated with dark clouds, suggesting a threatening storm or at the very least an ugly day.

It’s an evocative painting, and one that immediately places us on the water off the coast of Maine. Indeed, it puts the viewer not only on the water, but at the helm of the boat. But this is hardly a representational piece of work. We know what we are seeing and where we are going, but Marin insists we use our imagination.

“It is an iconic painting for his late career,” Balken said as she glided through the gallery for a pre-opening tour. “It’s important to include it in this exhibition because it’s a painting that begins to underscore his preoccupation with abstract elements. The correspondence with the later work of Jackson Pollock becomes especially apparent. These kinds of developments were predicted in a painting like ‘Lobster Boat.’ “

The exhibition includes both oil paintings and watercolors. Oils helped Marin capture the impact of natural elements, as well as their intense colors. Watercolors served his whimsical ideas, and gave his work immediacy. Balken suggests each medium informed the other.

“Modernism at Midcentury” is not strictly a Maine show. The state is well represented here; indeed, most of the work originates in Maine, and we are treated to dozens of sea paintings. But Balken’s examination also includes many pieces from New York and elsewhere, including several urban landscapes and the hills and rivers of New Jersey. We also see many paintings in which Marin made his frames an extension of the painted surface, some with more success than others.

Balken assembled the exhibition with loans from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; as well as other museums and private collections throughout the country.

The Portland museum collaborated with the Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass., to put the show together. After closing in Portland in early October, the exhibition will travel to the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, for a November opening and then to the Addison in January 2012.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Follow him on Twitter at:

twitter.com/pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.