The art connection between Maine and New York City is obviously deep and yet surprisingly elusive.

But Maine is more than some satellite of the American art capital. Along with Santa Fe, the Bay area and New York City, Maine has been one of the most significant American art centers with their own authentic identities.

Exhibitions around the state this summer poignantly illustrate the Maine/NYC connection with works on view by artists such as John Marin, Edward Hopper, Marsden Hartley, George Bellows, Winslow Homer, Paul Strand, Alex Katz, William Wegman, Richard Estes, Will Barnet and many other great artists with roots in both places.

One of the summer shows that addresses NYC/Maine distinctions is Thomas Connelly’s “Scenes I’ve Seen.” Rather than a New Yorker who summers in Maine, Connelly is a Mainer who often visits NYC. His paintings largely follow traditional modes of place: cityscapes, seascapes, landscapes and interiors. His focus on tonally consistent luminosity and handling of atmospheric and linear perspective reveal a respect for old-school technical challenges.

Connelly’s primary goal is to make good paintings. His work reveals sensibilities honed by a range of art from Vermeer and the Nabis to the photorealists and contemporary Maine landscape painting, but it also parses several conceptual distinctions between traditional and contemporary art. Connelly’s traditionalism is a conscious tool rather than a default mode, and he wields it well.

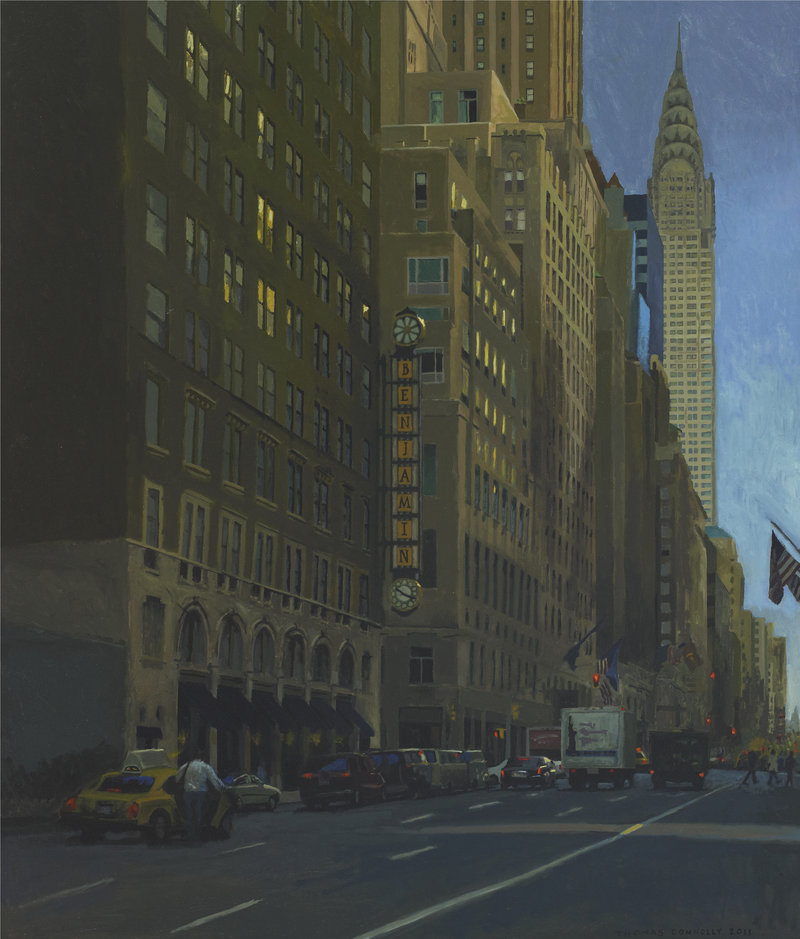

His “Benjamin Hotel” is a New York street scene over which towers the Chrysler Building. It’s commendable for the effort alone, because more than 500 windows had to be painted one by one. Its deft composition rides the perspective of the buildings’ setbacks down to the lower right of the painting.

A few details, however, say a great deal about what could otherwise be a scene from the 1930s: the cars are recent models, and a flicker of paint travels well out of a taxi’s brake light — hailing a debt to photorealism’s vocabulary of camera lens effects. As well, a campy image of the Statue of Liberty on the back of a van is a witty (if subtle) salute to postmodernism’s self-referencing.

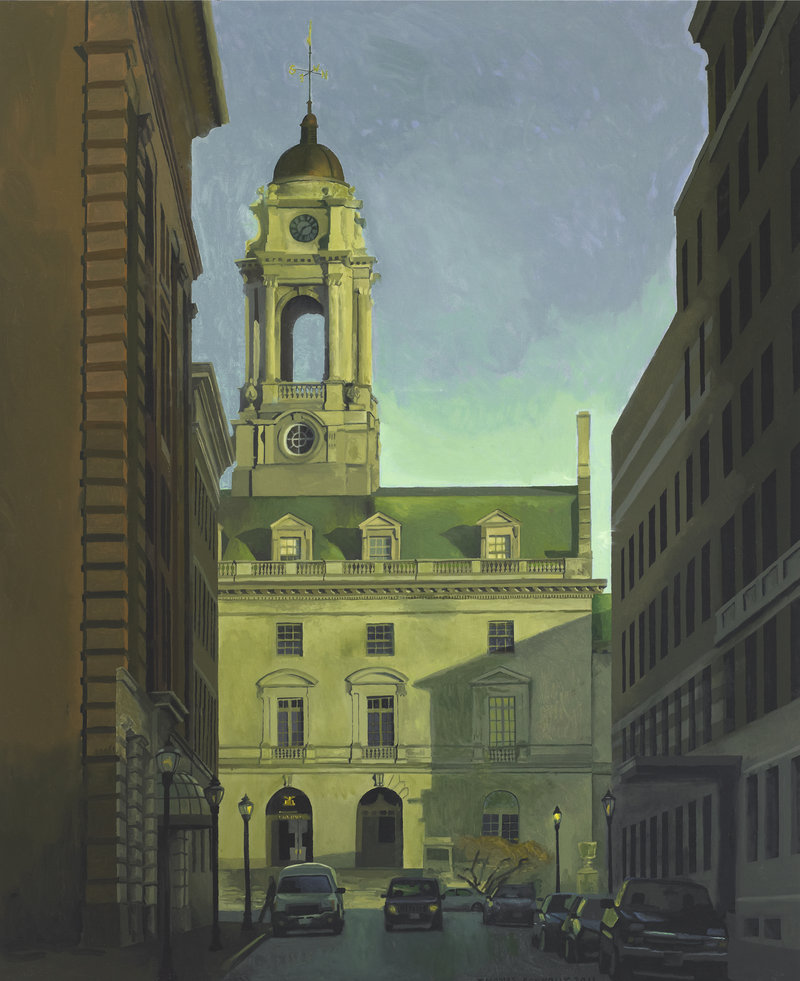

Portland gets similar treatment in “City Hall,” which peeks at the Beaux Arts structure through a tight street corridor. The similarly aged building on the left is a respectful repoussoir, but the ugly, contemporary office building on the right melts into a darkened mishmash that, seemingly embarrassed, wants to hide in the shadows. City Hall’s dashing cupola pulls our eyes from the heavy corridor up into the lofty light of open sky.

In short, Connelly seems to be using traditional painting as a vehicle to criticize some contemporary aesthetics (especially architecture) — something postmodernists would claim is the stuff of postmodernism itself.

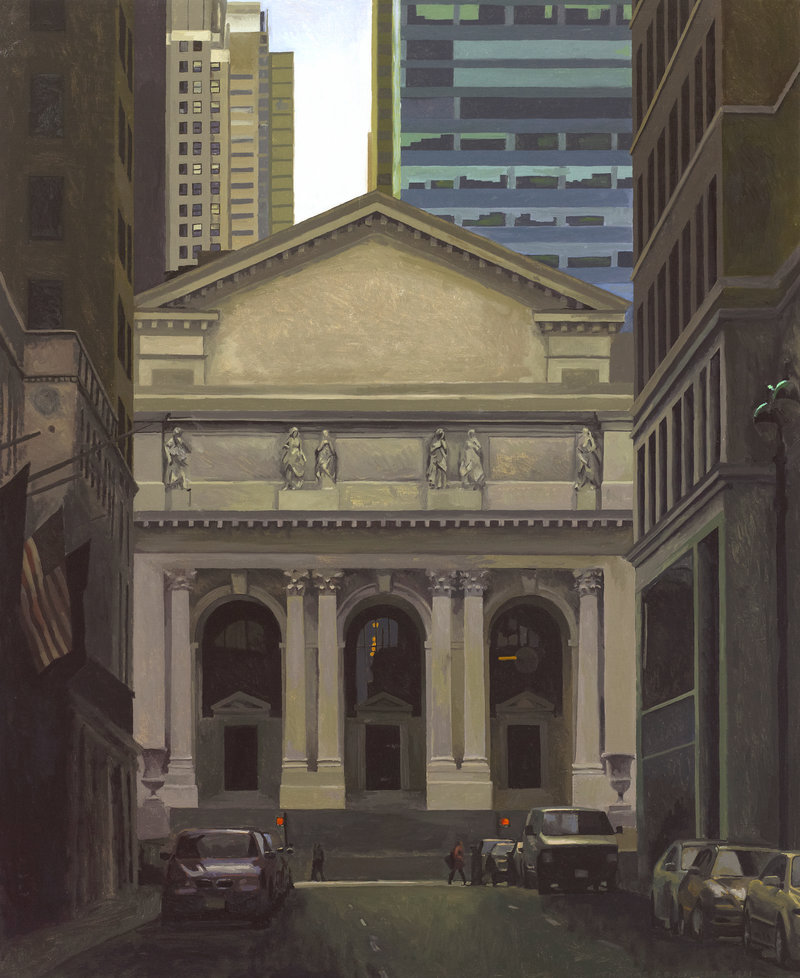

We also see this in “Warm Library,” in which a 1970s building rendered in a cold ’70s palette looms awkwardly over a wing of the elegant and charmingly rendered New York Public Library.

Another toast to the art of the past is a detail of a Vermeer painting in “Red Brick House.” The interior is calm, cool, casual and a bit flat, while the detail of the painting pops with dynamic contrast — the exact opposite of how images of paintings are usually depicted.

There are plenty of uncomfortable passages in Connelly’s paintings, but I don’t hold this against him. They actually reveal quite a bit about his decisions, his challenges and his revisions. As well, they prove he isn’t slavishly copying a photograph.

You could read “Wallpaper,” for example, as a painting that frustrated and eluded Connelly — or as a playful tribute to Vuillard. Considering how the wallpaper flatly circumvents a sharp corner and how the dining-room table plays geometrical games with the door and reflected grids, Connelly makes a clear case that the struggled elements of line, negative space, pattern and design make this a work about painterly devices and decisions.

The surprise component of “Scenes I’ve Seen” is a set of 12- by-14-inch landscapes Connelly painted in plein air. The landscapes flicker with a lively spontaneity simply not possible over the course of the month or so spent on each of the larger, detail-driven works. While they lack the tonal discipline of the studio paintings, they reveal Connelly has the talent to let his brush fly with unbridled energy. Compared to the severe sophistication of the NYC pictures, these are joyously unmediated.

Connelly says he is drawn to NYC because it’s America’s ultimate “man-made landscape.” Maybe it’s that New York is the peak of American culture, while the Maine landscape shows us what the New World looked like when Europeans first landed here. Connelly’s show certainly doesn’t fully answer the NYC/Maine question, but it casts some worthy light on this interesting issue.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.