Investigators hope the electronic data from the Amtrak train and tractor-trailer that collided Monday will provide clues about what caused the fatal crash on Route 4 in North Berwick.

Amtrak authorities recovered recorded data from the locomotive that should reveal its speed leading up to and immediately after the crash. The train typically runs at 70 mph through the at-grade intersections in North Berwick, officials said, and the gates are designed to close at least 20 seconds before the train arrives.

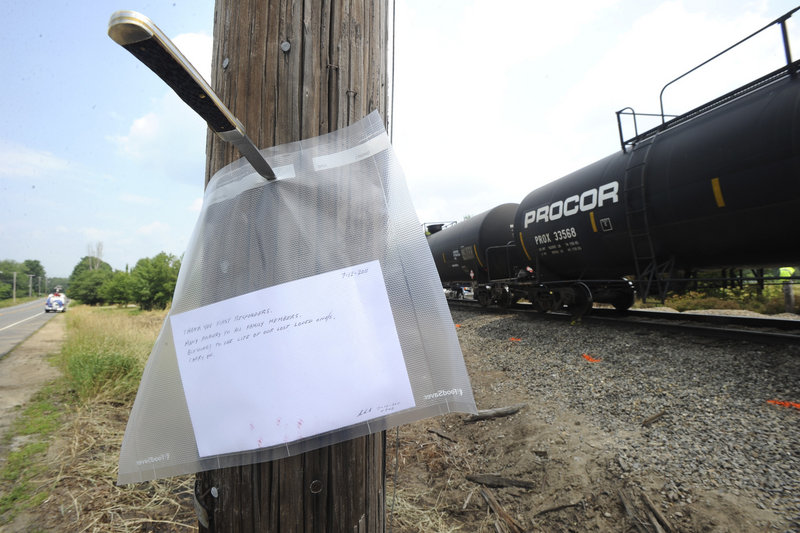

State police are trying to determine why the trash-hauling truck failed to stop before the gates and skidded into the path of the train. The collision sparked a huge fireball and killed the truck driver, Peter Barnum, 35, of Farmington, N.H.

The truck, a 2009 Kenworth trash compactor, had been inspected by the state in December and cleared for service, state and company officials said.

Skid marks that stretch more than 200 feet heading into the intersection may provide clues to how fast the truck was going. Police also are collecting cellphone records to determine whether Barnum was using one just before the crash.

The truck had a global positioning system, and police hope GPS records will shed light on the crash, said state police spokesman Steve McCausland.

Barnum drove for Triumvirate Environmental, a Massachusetts company that has a facility in Eliot. Barnum was driving 23 to 25 tons of trash from Kittery to the Maine Energy incinerator in Biddeford.

Barnum had worked for the company since April and was familiar with the route, said company spokesman Hugh Drummond.

Barnum had a clean driving for the past two years, Drummond said. The company has an above-average safety record, according to the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration.

The company’s drivers typically use secondary roads in the summer to avoid traffic jams on the Maine Turnpike, Drummond said.

The collision ignited a fire in the locomotive, and flames seared the coach immediately behind it as smoke filled passenger compartments. There were 112 passengers in four coaches and a cafe car.

Once the train stopped, a conductor and an assistant conductor helped evacuate the cars. A food service employee gave passengers water while they waited to be driven from the area.

The collision badly damaged the locomotive, whose engineer is lucky to be alive, said Patricia Quinn, executive director of the Northern New England Passenger Rail Authority, which operates Amtrak’s Downeaster service.

“Once he got back on his feet again and was able to see and find his way to the back, after he leapt out of the burning locomotive, his concern was, ‘What do we do to help the passengers,’” Quinn said. “The engineer was extremely fortunate to get out alive.”

She said the train “was broken apart by the impact,” and the separation between the locomotive and the coaches kept the fire from spreading.

Cliff Cole, an Amtrak spokesman, said the railroad does not plan to release the names of the workers who were on board at the time of the crash.

The road remained closed Tuesday while state and railroad workers cleaned up trash that littered the intersection and lined the tracks.

Amtrak personnel were checking to make sure the railroad’s equipment operated properly and its staff followed procedures. Springfield Terminal Railway, which maintains the track, was checking to make sure the crossing equipment worked as intended. State police focused on the truck and the driver.

“There’s been no determination of an estimate of speed,” said McCausland. “It’s unclear why he didn’t stop in time. The truck cab was split in four pieces and some of it burned, so I don’t know what we have to work with.”

The destruction of the train engine isn’t expected to affect service. The Northern New England Passenger Rail Authority contracts with Amtrak to provide equipment and staffing for the Downeaster. That means it is Amtrak’s responsibility to replace the coach, Quinn said.

“This is a loss for Amtrak. The equipment is tough to come by. It’s in demand,” Quinn said. “Right now we have enough to get by. If something breaks down, we don’t have a spare.”

Officials are working to determine whether the warning lights and gates at the intersection operated as intended.

Warren Flatau, a spokesman for Federal Railroad Administration, said his agency sent investigators to Maine to interview the crew and signal maintainers, and to inspect the safety systems.

Flatau said the flashing lights and gates at railroad crossings are controlled by a system that maintains an electrical current in the tracks. The system engages when a train trips the circuit. The lights at the crossing start flashing, and the red-and-white gates drop.

Flatau said federal regulations require at least 20 seconds from the time the gates extend to when the train crosses the road. He said the interval is long enough for drivers to stop, but short enough that they don’t take the signals for granted.

Federal rules require the operator to blast the train’s whistle 20 seconds before the train arrives at a crossing.

The crossing in North Berwick had a “constant warning time” system, which ensures that motorists have the same amount of notice regardless of how fast the train is going. Freight trains on the line go much slower than the passenger trains.

David Davis, who lives one house away from the intersection and saw the crash, said he wasn’t timing it, but 20 seconds seems a fair estimate of the time between when the crossing gates closed and the collision happened.

“I heard the bells and I knew the train was coming down shortly afterward, and then I heard the squeal of the tires and there was smoke coming out from under the trailer,” Davis said. “Then the train was right there and I saw he couldn’t stop.”

Some Amtrak passenger cars weigh 148,000 pounds, and locomotives can weigh 250,000 pounds, said Flatau.

The Downeaster trains, which typically have three or four coaches along with a locomotive cab car and a cafe car, take about a half-mile to stop, Quinn said.

Flatau said he doesn’t believe that the warning system failed in Monday’s crash. Warning system failures are rare, accounting for only one or two accidents a year, he said.

The Federal Railway Administration oversees the safety of freight and passenger trains, including Amtrak and about two dozen commuter rail lines.

The warning systems are maintained and tested by the owner of the track, Springfield Terminal Railway, an affiliate of North Billerica, Mass.-based Pan Am Railways.

Rob Culliford, Pan Am’s senior vice president and general counsel, would not answer questions about the crash or the track maintenance at the site.

Staff Writer Ellie Cole contributed to this report.

Staff Writer David Hench can be contacted at 791-6327 or at: dhench@pressherald.com

Staff Writer Jonathan Hemmerdinger can be contacted at 791-6316 or at: jhemmerdinger@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.