Robert Evans, the Paramount Pictures executive who presided over a remarkable range of hits – notably “The Godfather,” “Chinatown,” “Rosemary’s Baby” and “Love Story” – and whose rakish and erratic personal style embodied the remarkable rise, fall and rise of a Hollywood player, died Oct. 26. He was 89.

Monique Moss, a spokeswoman with the Integrated PR Agency, confirmed his death. Other details were not immediately available.

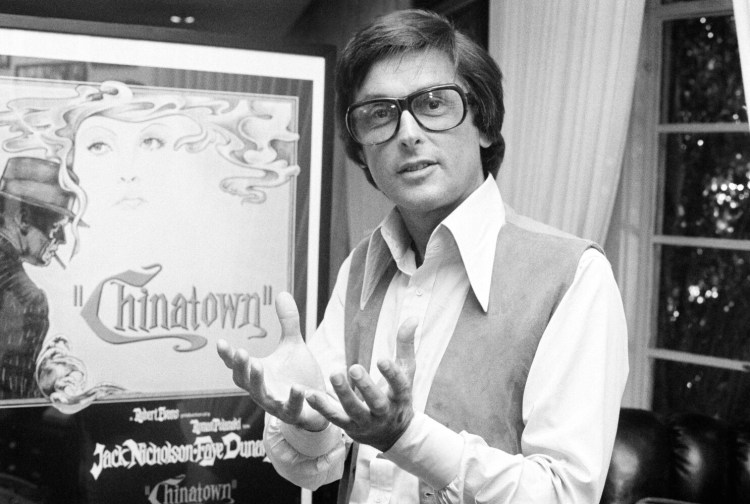

With his gravelly voice, large-framed designer glasses, perpetual tan and fondness for gold chains and suede jeans, Evans brimmed with a rakish confidence and showmanship that propelled his career in the 1960s and 1970s. He was long considered one of the savviest production chiefs in Hollywood, but cocaine abuse gradually derailed his career.

He pampered his stars, paid his writers generously and created – except for rare occasions of explosive conflict with temperamental filmmakers – an atmosphere where the art of moviemaking seemed to matter more than the bottom line. But eventually the profits came.

As Paramount’s head of worldwide production from 1966 to 1975, his commercial choices and hunch for talent were credited with helping lift the company’s sagging fortunes with a staggering variety of popular and often critical hits.

They included “The Odd Couple” (1968), “Goodbye, Columbus” (1969), “True Grit” (1969), “Love Story” (1970), “The Conformist” (1971), “Serpico” (1973), “Paper Moon” (1973), “The Great Gatsby” (1974), “Death Wish” (1974), “The Longest Yard” (1974) and three celebrated Francis Ford Coppola dramas, “The Godfather” (1972), “The Godfather, Part II” (1974) and “The Conversation” (1974).

Evans and one of his lieutenants, Peter Bart, came to champion directors other studios wouldn’t hire – and who worked cheaper. Roman Polanski was considered a young wild card from Europe when he was entrusted with the adaptation of Ira Levin’s Gothic novel “Rosemary’s Baby.” The 1968 film made a movie star of Mia Farrow.

Hal Ashby had been working mostly as a film editor when Evans hired him to direct “Harold and Maude” (1971), a dark comedy about a suicidal 18-year-old boy (Bud Cort) and the life-affirming 80-year-old Holocaust survivor he befriends (Ruth Gordon). The film drew a devoted following over the years.

“My business is gambling,” Evans once told Esquire. “It’s the gambling instinct that makes me tick.”

He often claimed to have no idea what many of the scripts were about but maintained that the right talent packaged together (actor Jack Nicholson, director Polanski, writer Robert Towne) could make for a dazzling success (“Chinatown”).

“That’s the problem with today’s business,” Evans told the Los Angeles Times in 2002. “It’s not an art form, it’s a barter form. The studios are run by committees of MBAs, but I’ve never seen an MBA who knows how to make people cry.”

Above all, Evans was a throwback to an earlier age in the movie capital, when the public and private lives of moguls such as Darryl F. Zanuck and Jack Warner could often be as compelling as the movies they made.

As a young man, Evans was blessed with pretty-boy looks and conveyed a sex appeal that won him many female admirers who happened to be the wives of very influential men. Actress Norma Shearer, the widow of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer mogul Irving Thalberg, launched Evans’ brief but inauspicious career as a movie actor after spotting him poolside in 1956.

He soon set his mind on producing – “the guy who makes the decisions,” he told The New York Times, “not the guy who has the decisions made for him.”

Yvette Bluhdorn, the French-born wife of industrialist Charles Bluhdorn, smoothed Evans’ path to run one of her husband’s smaller properties, Paramount Pictures.

“He’s gorgeous,” Yvette Bluhdorn was reported to have told her husband, according to Peter Biskind’s film history book, “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls.” “We’ve got to get a good-looking guy, real sexy, to run the studio.”

So in 1966 Evans catapulted from obscurity to one of the most powerful jobs in Hollywood. At the time, American cinema was on the verge of an artistic renaissance after years of making expensive flops such as the musical “Dr. Dolittle.”

Influenced by a new generation of adventurous European filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard, young directors like Coppola, Peter Bogdanovich and William Friedkin would shrug off convention and create a vogue for grittier material and more experimental filmmaking.

Evans managed both to placate the money men at Gulf & Western, who wanted to sell Paramount because of its wan revenue, and become a peer of Hollywood’s rambunctious talent.

More than the studio, it was Evans’ home in Beverly Hills that served as his most effective place of doing business – where business leaders cavorted with sumptuous starlets, where Jack Nicholson and Warren Beatty partied, and where Henry Kissinger and Dustin Hoffman could be found on the tennis courts.

Evans was married seven times to a succession of models and actresses, including “Love Story” star Ali MacGraw and former Miss America Phyllis George. His fifth marriage, to “Dynasty” actress Catherine Oxenberg, was annulled after nine days in 1998. Information on survivors was not immediately available.

His marriages could seem like interruptions to Evans’ rollicking bachelor life, around which legends grew. It was reported in “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls” that when his housekeeper delivered his breakfast of black coffee and cheesecake in the morning, she included a note under a plate with the name of the woman sharing his bed, in case his memory needed jogging.

There was a darker tinge to Evans’ personal affairs. He struggled with a cocaine addiction for many years. And he drew unwanted headlines when Coppola’s 1984 film “The Cotton Club,” which Evans produced, was linked to a real-life kidnapping and murder case.

The ensuing court case – and many bridges burned – left Evans a Hollywood pariah. Exhibiting a Gatsby-esque skill for reinvention, he returned to favor as the grand old man of the entertainment colony when his 1994 memoir, “The Kid Stays in the Picture,” became a bestseller. A documentary film, narrated by Evans, followed in 2002.

Capitalizing on the attention, Comedy Central aired a short-lived animated series based on Evans’ life. It was called “Kid Notorious.” In the cartoon, as in life, Evans had his English-accented butler, a starlet in his bed and an air of cheerful decadence.

Robert J. Shapera – the J “standing for nothing I knew of,” he once wrote – was born in New York on June 29, 1930. He described his father as a frustrated pianist who went to dental school and ran his practice in Harlem. He was 10 when his father changed his children’s last name to Evans, in tribute to their dying paternal grandmother, whose maiden name was Evan.

Evans managed to finish high school while chasing (and catching) Broadway showgirls and, by his 20s, had drifted into modeling menswear. He became a partner and salesman for the women’s clothing line Evan Picone, which had been co-founded by his brother Charles.

In 1956, Evans was in Los Angeles on a sales trip when he was spotted beside the Beverly Hills Hotel’s pool by Shearer, who thought the young sunbather resembled her late husband. As it happened, MGM needed someone to play Thalberg in the Lon Chaney biopic “Man of a Thousand Faces.”

He got the part, but Evans’ acting career was brief and forgettable. During filming of the 1957 adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises,” nearly everyone involved rebelled at the casting of Evans as Mexican bullfighter Pedro Romero.

But in a display of power that impressed Evans – and which he used for the title of his memoir – Twentieth Century-Fox studio chief Darryl F. Zanuck told the crew, “The kid stays in the picture.”

By 1962, flush with cash from the sale of Evan Picone to Revlon, Evans tried to make the leap to producer. One of his methods was to buy the screen rights to books before they were published; when they became bestsellers, Evans traded the rights for a chance to produce.

A New York Times profile of Evans by Peter Bart soon caught the attention of Charles Bluhdorn. It wasn’t long before Evans was running Paramount with his new friend and confidant, Bart, as his right-hand man.

Like all the studios, Paramount was at once stuck in the past – as symbolized by the musical “Paint Your Wagon,” a costly musical that tanked in 1969 – and trying to read the counterculture moment symbolized by the biker film “Easy Rider.” And yet what saved the studio, and Evans, was a script that had been rejected all over town.

“Love Story,” a sappy melodrama written by Yale University classics professor Erich Segal, was the story of the doomed romance between two Ivy League lovers, a rich jock named Oliver Barrett IV and a working-class intellectual named Jennifer Cavilleri.

Evans threw himself into the making of the film, rejecting several scores before getting Francis Lai to pen the film’s Oscar-winning theme song. “Love Story,” which starred MacGraw and Ryan O’Neal, shocked the Hollywood establishment when it broke box-office records upon its release on Christmas Day 1970.

Flush with “Love Story’s” success, Evans turned next to “The Godfather.” Years earlier, for a pittance, he and Bart had optioned an unfinished potboiler called “Mafia” by an obscure author named Mario Puzo. Mob movies were not considered big draws, but when Puzo’s novel became a sudden bestseller, “The Godfather” was poised to become Paramount’s next big hit.

Making the film was a tumultuous experience for all involved. “Francis and I had a perfect record; we didn’t agree on anything – from editing to music to sound,” Evans later wrote of working with Coppola.

“The Godfather” (1972) and its sequel, “The Godfather: Part II” (1974), won multiple Oscars, helped launch the careers of Pacino, Diane Keaton and James Caan, and resurrected the mob movie genre.

“The Godfather” was a commercial and artistic triumph but coincided with the disintegration of his marriage to MacGraw, who left him for actor Steve McQueen.

Evans also was growing increasingly restive as a mere employee of the studio; he wanted to own a stake in his films. He got his chance by producing the 1974 L.A. noir “Chinatown,” working with pals Nicholson, Polanski and Towne, whose screenplay won the Academy Award.

But after “Chinatown,” Bluhdorn brought in Barry Diller to be the studio’s new production chief. Evans remained on the lot, producing films such as the lauded thriller “Marathon Man” (1976), starring Dustin Hoffman and Laurence Olivier. But other movies he produced – including “Black Sunday” (1977), about a terrorist attack at the Super Bowl, and Robert Altman’s live-action “Popeye” (1980) – were duds.

In 1980, Evans pleaded guilty to cocaine possession; he was sentenced to one year’s probation. Worse trouble came his way when he met a 33-year-old road show promoter named Roy Radin, who became an investor in “The Cotton Club.”

Directed by Coppola and set at a Harlem jazz club in the 1930s, “The Cotton Club” was widely panned. By that time, Radin had been found dead in a dry creek bed off a highway northwest of Los Angeles. He had been shot 13 times.

Ultimately, four people were convicted in Radin’s death, including Karen “Lanie” Greenberger, a former drug dealer and girlfriend of Evans who had introduced Radin to the producer. The notion that Evans was orbiting an underbelly of drugs and murders-for-hire made him persona non grata for years.

Eventually, Evans returned to Paramount. The movies he produced – including “Sliver” (1993), “The Saint” (1997) and “How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days” (2003) – were on a far more modest scale than before, but he remained full of the bravado that defined his heyday.

“My life reads like fiction,” Evans told the Los Angeles Times in 1998. “Cheap fiction. I was the lawless. But I came back from Jesse James-ville.”

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.