WESTBROOK – Al Hawkes figures he’s not getting any younger. If he doesn’t tell this story now, it might never be told.

Now 81 and 11 years deep in his battle with Parkinson’s, Hawkes is in the process of putting his life and legacy in order. His own personal story is widely known. He’s received more than 25 state, regional and national awards for his music and is regarded — in some circles, revered — as a bluegrass pioneer both in Maine and on the national scene.

And rest assured, Hawkes remains active, musically and otherwise. If the disease shows its effects on his movements, it has yet to diminish his ability to perform and sing, or his enthusiasm. His fingers remain nimble, and he is entering this challenging phase of his life with dignity and grace.

This particular story has nothing to do with the guitar, mandolin or his standing up to Parkinson’s. It is a story about the heroic love of family, a brother’s protection of his sister and an enduring zest for art and creative expression against all odds.

Lately, Hawkes has been thinking about his great aunt, Julia M. Hawkes, who was born before the Civil War and died in 1934 at age 80. She lived on the family farm in Westbrook, a stone’s throw from Hawkes’ home today.

Al Hawkes was just a lad when his father’s aunt died, and he has no memories of his Great-Aunt Julia. Growing up, what he knew of her he learned mostly through his father’s stories.

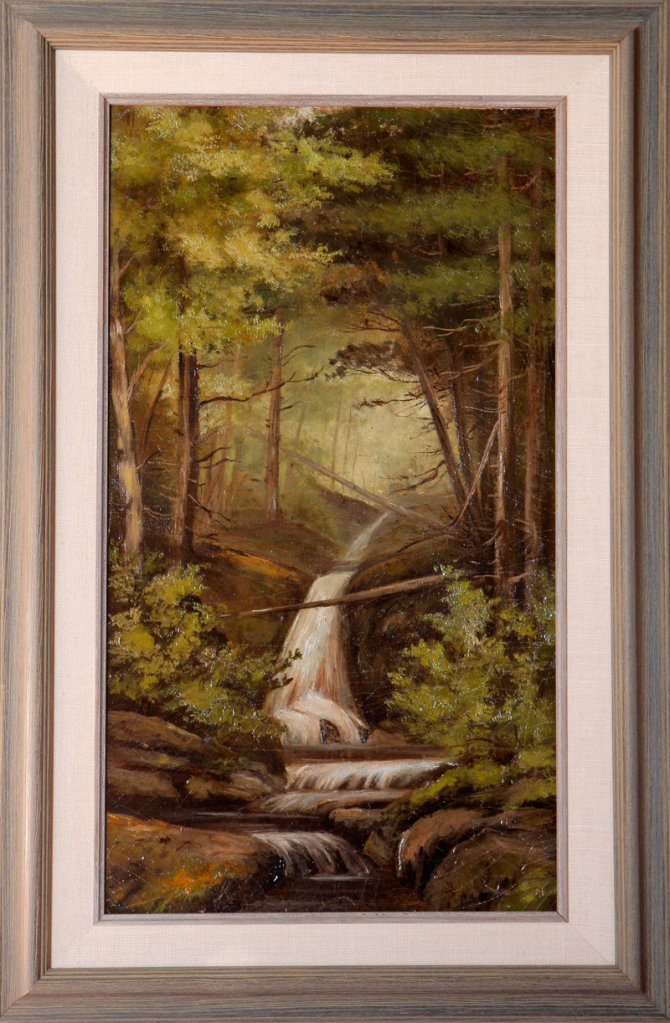

But all his life, Hawkes has been exposed to his aunt’s creativity, and perhaps even shared her expressive genes. She was a dedicated painter, working mostly in oils and also in watercolors. She painted lush scenes of the Maine landscape and barn scenes in and around Westbrook, of Highland Lake and other local spots. She had a keen eye for flowers and executed many well-done still lifes of peonies, lilies and other colorful flowering plants.

Though they have never been shown publicly, her paintings have hung in the Hawkes’ household for many years, and in his parents’ house before that. Hawkes always appreciated the paintings, but barely gave them a second thought.

Now that he has begun pondering his own life in a deeper way, he finds himself thinking more about his great-aunt.

“As I get older, I appreciate what she did. I walk through this house and I see the pictures that she painted, and I think about the lengths she had to go to do what she loved,” he says.

Hawkes’ great-aunt painted in secrecy. Her Quaker religion discouraged creative expression, and Julia never fully celebrated her artistic gift. Indeed, she kept it hidden most of her life, and only after her own father died did her paintings come out of hiding.

Her father would not have approved, Al Hawkes said. “She was not supposed to create. The Quakers believed that God created everything,” he explained.

Great-Aunt Julia had the courage to paint because her brother, James Frank Hawkes, gave her a private place to work and provided a cover to account for the time she dedicated to her art. He was a blacksmith and serviced the stage coach that came from Portland. Frank bought his sister her paintings supplies, and secreted her away in the loft of his barn. He paid her to do bookkeeping, but gave her the means to paint.

Whatever money she made, she sent away for mission work overseas.

“All she wanted to do was paint,” Al Hawkes says, sitting in the living room of the house he shares with his wife of 60 years, Barb. “The family was very strict. They were very religious, and painting was a sin. It was considered blasphemy, and she would be punished. But her brother protected her. He provided her paints and easels and the wood for her frames.”

Hawkes and his wife, with the help of a family friend, Eileen Grant, are in the process of documenting his aunt’s work. He’s not sure how many paintings she completed — somewhere around 200, most likely. Many were lost in a fire in the late 1970s, and many among the surviving paintings were damaged by the fire or suffered from years of attic storage.

But more than 100 survive, and many are in good or great shape. Al and Barb have cleaned and framed several, and they recently consulted with Bonnie Mattozzi, director of the Maine Project for Fine Art Conservation in Portland, about the best way to proceed with the rest. They would like to conserve as many paintings as possible, and arrange an exhibition or sale.

Mattozzi spent several hours with the Hawkeses recently, and came away impressed — with the story of Julia and her brother, but also with the work itself. While many of the paintings are in rough shape and beyond conservation, many more are worth saving, she said.

“Some of the pieces are really beautiful,” Mattozzi said. “They were just pulling out paintings, one after another. They knocked our socks off. Several paintings were really well-executed. Some were primitive, some were very beautiful and very heartfelt. They are very honest paintings.”

For Hawkes, this effort represents the opportunity to preserve a small piece of Maine history, as well as a family legacy. His great aunt never married, and might easily be forgotten if not for the gravestone that marks her final resting place in the family cemetery close by. Preserving these paintings ensures that her story will be told for generations to come, he said.

Hawkes’ own legacy is secure. He’s made many records, has been the subject of a documentary, and his fans from Maine to Tennessee and beyond will listen to his music long after he’s gone. He will be remembered.

But as he ponders what his great aunt accomplished in absolute anonymity and with the expectation that her work would never be seen, he wonders what influence she had, however remote and perhaps in a genealogical way, on his decision to make music.

“I’m absolutely fascinated by what she did,” he says. “I look at her paintings and I say, ‘I’m not a painter, but I am an artist.’ I think it’s in my blood. I think I had what she had. She had a driving force to paint. I had a driving force to make music. I write songs now, and they just come to me in a flash. I think she was the same. I think she saw something and said, ‘I’ve got to paint that.’ “

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.