Every now and again, a painter comes along who forces you to reconsider everything.

Lesley Vance is that painter.

Vance, who has no ties to Maine — or had none until Bowdoin College invited her to show her paintings — was born in 1977, graduated from the University of Wisconsin in 2000, and earned a master’s from the California Institute of the Arts in 2003.

The Whitney Museum of American Art included her in its 2010 biennial, and things have been a bit crazy for her ever since. She is considered a rising star in the contemporary art world. Critics love her, and her work is making its way into prestigious private collections.

But Vance has lacked the splash of a solo museum show. Until now.

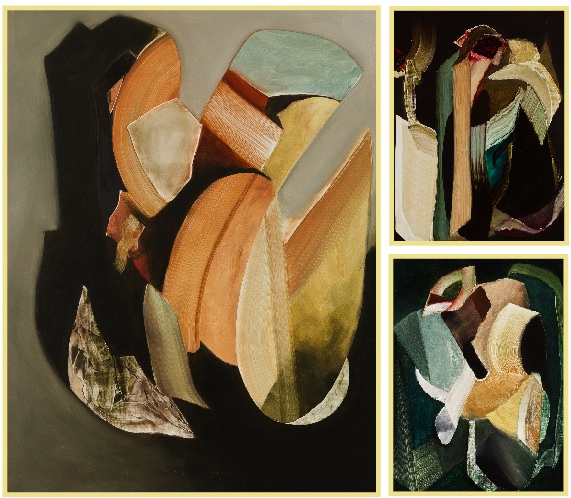

A series of her paintings — mostly smallish oils that exist somewhere on a trajectory between classical still lifes and surrealist excursions — is on view at Bowdoin College Museum of Art through July 1.

When Bowdoin curator Diana Tuite saw Vance’s paintings at the Whitney biennial, she wondered aloud, “How has no one done a show yet?”

“So many people had that same feeling coming out of the biennial, that this was work that would be sustaining,” Tuite said. “It was amazing how people remember seeing it. It really stood apart. We felt strongly about it, and wanted to get involved.”

Tuite called Vance to pitch the idea of a solo show, and the artist’s response was predictable: Where’s Bowdoin?

We can forgive a Californian for not knowing about this gem of a museum in Brunswick. But rest assured, she knows about Bowdoin now.

Vance was on campus for a mini-residency recently, meeting with students and doing a Q&A and discussion of her work with art professor and painter Mark Wethli — who rightly observed that walking into a gallery of Vance’s paintings somehow feels like walking into a gallery of work by the Old Masters. Her work reads like a 17th-century still life with saturated colors and glistening surfaces.

But the images themselves are non-specific. They are not flowers, fruit, portraits or anything remotely recognizable. They are abstract images, finely constructed.

This show is getting attention because her paintings are so unusual, Tuite said. They are old world and modern. They are exercises in abstractions that look like realism.

They might be meditations on floral arrangements or stalky vegetables, but they’re not. They are textured, developed and highly refined paintings that are full of gesture and all about color, form and emotion.

They are, in essence, collages of paint upon paint, though some look as if they are accented with ribbons of twisted fabric.

“She is invested in creating a painting that is enigmatic and self-sufficient, in a way,” said Tuite.

Vance starts her process by collecting objects and arranging them as if to create a still-life composition. She controls the lighting to cast shadows and beacons. Instead of sitting down to paint, she then takes photographs of her arrangement.

It is then, from her photographs, that she begins her painting process. She often will spend two days preparing her canvas surface, applying layer upon layer of gesso to create an ivory-like base.

The painting comes quickly after that — wide sweeps of color with her brushes, hard-cut surfaces with a palette knife. Her lines are clean and rigid, and almost architectural, although her paintings are entirely two-dimensional.

In an interview with Tuite published in a small catalog that accompanies this show, Vance described her paintings as being “in a constant state of transformation — almost as if the painting has stopped in this moment and has been suspended there. It is one of the reasons why a painting in general is so impossible to describe, because it possesses its own peculiar quality of time.

“I am always thinking about the plasticity of form. In my work, many actions lead to the final image, and yet when I look at my paintings, I can imagine them existing in a different way at a future point, so they somehow exist in a few dimensions of time at once — if that makes sense.

“And although there are many erasures, many moments of completely irrational periods of frustration leading to destruction that go on over the course of my making a painting, in the end, it must feel like it made itself.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.