Those of us of a certain age likely had an intimate relationship with the vinyl record.

Remember slicing the thin plastic wrapper with your thumbnail, peeling it off and turning the album jacket over and over to look closely at the artwork and peruse the song titles? We would slide out the dust cover and devour the liner notes and musician credits. Some of the really cool albums had a poster or other surprises inside.

We’d remove the vinyl record from its the jacket, place it on the turntable — taking care to not smudge the grooves with our fingers — drop the needle, listen for that hiss and crackle, and then finally the first notes of the record.

“There was a ceremony that we had with an album,” says Maine artist Amy Ray, 51, who co-curates a new exhibition that uses the vinyl record as the primary medium. “I never felt that kind of closeness to CDs, and certainly not with virtual music. It was almost a ceremony to open that album and handle it oh so carefully.”

The exhibition, aptly titled “The Vinyl Show,” opens with a reception from 5 to 8 p.m. Friday at Engine in Biddeford and remains on view through Oct. 20.

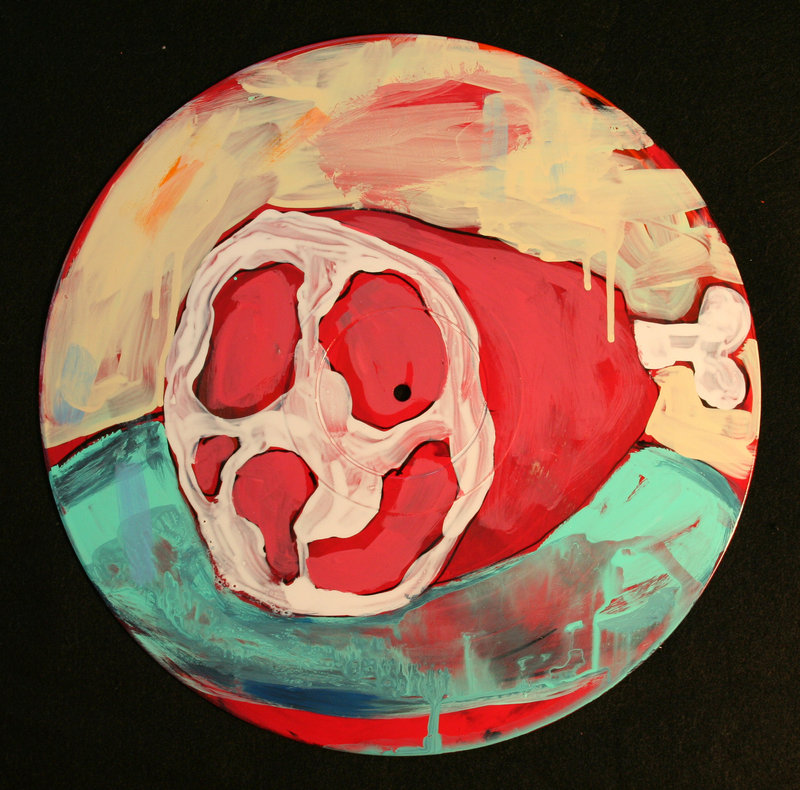

Two dozen Maine artists participate in the exhibition. They had few rules, other than one: The record itself — not the jacket — had to be the primary material. “I really wanted people to focus on the vinyl itself, just that black orb,” Ray said.

Sculptor Patrick Plourde turned his vinyl into colorful, three-dimensional flowers. Kimberly Convery used the vinyl as a surface for drawings. Rachael Eastman broke apart her vinyl and created a spine-like vertical piece, using the bits of the record, painted gold, to resemble a bone-like structure.

The project attracted some well-established Maine artists, including Mike Libby of Insect Lab, Lin Lisberger, Abby Shahn, James Chute, Johanna Moore of Artifacts Restoration and others.

As each new piece came to her, Ray delighted in the artists’ creativity. “People are drilling holes, people are melting, people are cutting,” she said. “Some are using it as a surface, and others are treating it as a round canvas. Some seem to be responding to a specific music memory or an album memory. Others are responding to the physicality of the vinyl itself.”

The genesis of this idea began in a thrift store. Ray, who lives in Monmouth, ran across a stack of old records while browsing The Vestry in Monmouth. It was not a stellar collection, and the pile had been there for months. She figured there were at least 1,000 albums.

One day when she visited the store, they were being offered for free. Those that did not get claimed were bound for the local dump.

“It haunted me to think they would end up in the landfill if no one claimed them that day, even if they were mostly just crap,” she said. “I was in my studio later that day and thought, ‘Wow, they would be a great material.’ So I went back and filled my truck.”

Ray put out the call casually, mostly through her Facebook connections. At Engine, executive director Tammy Ackerman also recruited artists.

People responded immediately. “Artists had this intimate feeling that it would be a good material to handle and work with,” Ray said.

Curiously, many artists chose albums that had meaning to them — a favorite artist or album. It’s curious because the album title and musician or band name are not apparent in the final pieces. Everybody seemed careful about what they picked from the pile, Ray said.

“There is just such a spirit to them, such a reverence. It’s just so different now,” Ray said. “You had to use two hands. You usually had to crouch down on your knees and place the record carefully on the turntable.

“Virtual is great. New is great. But back then, there was an intimacy associated with handling an object.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.