My childhood ended at 9:45 a.m. on June 26, four days before my 50th birthday.

That was the moment when my dad fought for his last breath and slipped away from the world.

And that was the moment I stopped being someone’s child, beginning my travels through the disorienting and surprising world of grief.

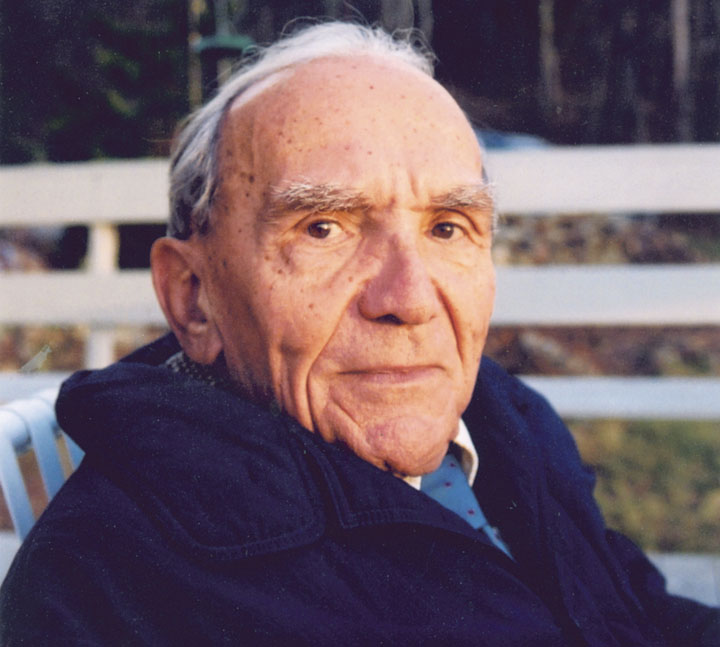

His death was not a surprise. My father was 91 years old and in declining health. He’d had a long and productive life — mostly happy, but he’d outlived his hearing, his ability to get around and my mother. He was ready for the end, and I thought that I was, too.

But I was not. And that was a surprise.

We live in what we like to think is an orderly world, where things happen when they are supposed to in predictable patterns, like a student moving through the grades at school. But the world doesn’t always make sense even when the patterns are predictable. Grief is a powerful emotion, whether you think you are ready for it or not.

I’ve always thought that a dignified death after a long and full life, where there is enough time for everyone important to say goodbye, was nothing to cry over. Finding out the opposite was true was Surprise No. 1.

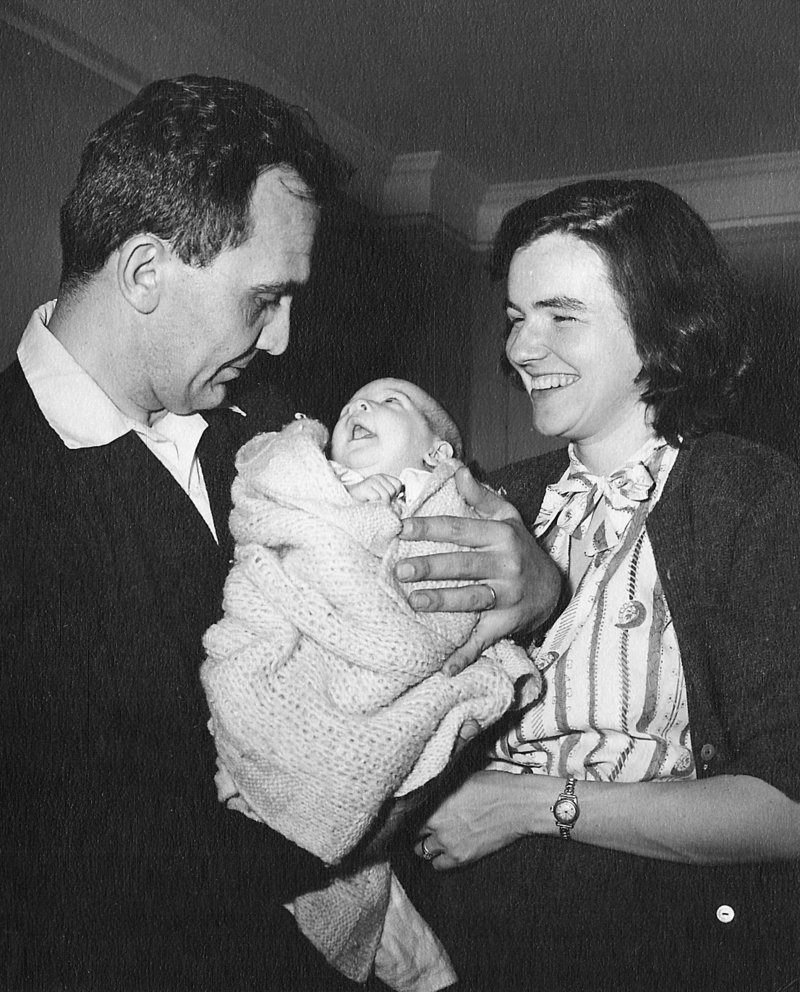

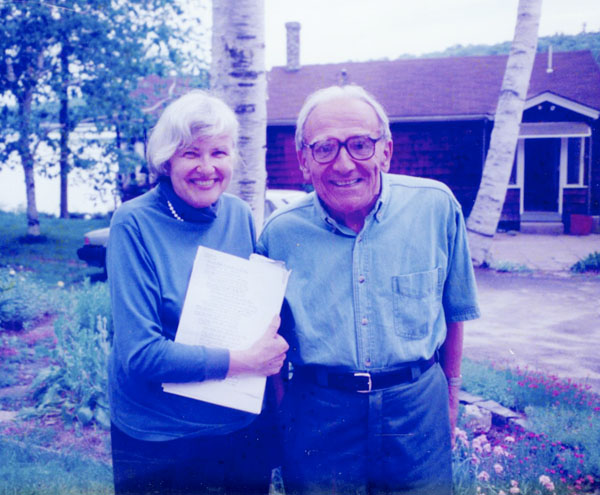

Over the years, my father had let go of many parts of the things that made him who he was. He retired and moved away from the people he used to work with. When my mother died, he lost his partner, his best friend and the keeper of his memories. Without her, he lost his interest in movies and New Yorker cartoons and his taste for a glass of wine with dinner. Gone, too, were the old friends she used to keep in touch with through birthday cards and Christmas letters.

His world got smaller and smaller, eventually coming down to a recliner, a TV with the sound off and a wall clock he used to keep careful track of his days.

Having done so much downsizing over the years, I thought we had already said our goodbyes. Surprise No. 2.

Almost as soon as he died, my father was restored in my mind to all the things he had ever been.

When I imagine him now, it’s not the sick old man that I see, but the star student, the brave refugee, the wise professor and, mostly, the guy of 20 years ago, in all his power. A career behind him, surrounded by his family, telling the old stories that could still make him laugh so hard he would actually cry.

That was the father that I lost, and he came back to me so quickly and with such force it took my breath away.

Surprise No. 3 is the disorientation that comes from suddenly not having parents.

If you think of the word “orient” to mean understanding where you are in the world (literally “to face east”), you can imagine the disorientation that comes when one of the fundamental relationships that define your life no longer exists.

If you are not someone’s child, no matter how old you are, what are you?

It’s a question that my parents, their parents and everyone who has outlived his parents has had to answer, but for me the confusion was real and spilled over into other important relationships. Like a panicked swimmer who starts drowning his rescuers, I got into fights with my wife and daughter — really stupid fights. Once you lose your parents, what relationship is safe?

I’ve heard of people who dramatically change their lives. I have a friend who underwent a male-to-female sex change in her 60s, even though she’d known from childhood that she was in the wrong body. “I had to wait until my parents died,” she explained.

There are whole libraries written about how people experience loss. Most of us can recite Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’ five stages of grief (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance) and have some idea that this is a process that needs time to work through.

But that makes it sound so much more organized than what really happens (“Here we go, depression, right on time! I should be due for acceptance this time next Tuesday …”).

A much better description of the process is one I heard when I bumped into a friend in Target six years ago, shortly after my mother died.

My friend had just lost her father and was at the funeral with her big Irish family. Her uncle took her aside and told her that grief was like eating hard-boiled eggs.

“He said, ‘To get through this, you’re all going to have to eat a dozen hard-boiled eggs,’” she told me. “‘You can eat them all at once and feel sick, or you can eat them one at a time — think about it.’“

Her interpretation of this advice was to handle your sorrow in small doses, but I think it also speaks to the solitary nature of grief. Even in a family, everyone is on his own.

One of the most touching things to happen since my father’s death is the way people have come up to me to tell me how their parents died. I could sense their sympathy for me, and also something else.

The months and years had passed and the acceptable time for public mourning was long over for them, but there is some little part of their grief that doesn’t go away.

Which is comforting, because it means that “moving on” doesn’t mean forgetting about what you’ve lost. That’s why I hope I also hold on to some of the sadness, which, I suppose, is another surprise.

Greg Kesich is the editorial page editor. He can be contacted at 791-6481 or at:

gkesich@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.