When William Hoy was a minor league baseball player, opponents would try to get an advantage by pitching to him when he wasn’t looking.

Hoy was deaf, so he had to turn around and read the lips of an umpire to see if each pitch was a ball or a strike. He worked out a system of hand signals with his third-base coach so he could learn if pitches were balls or strikes without turning away from the pitcher.

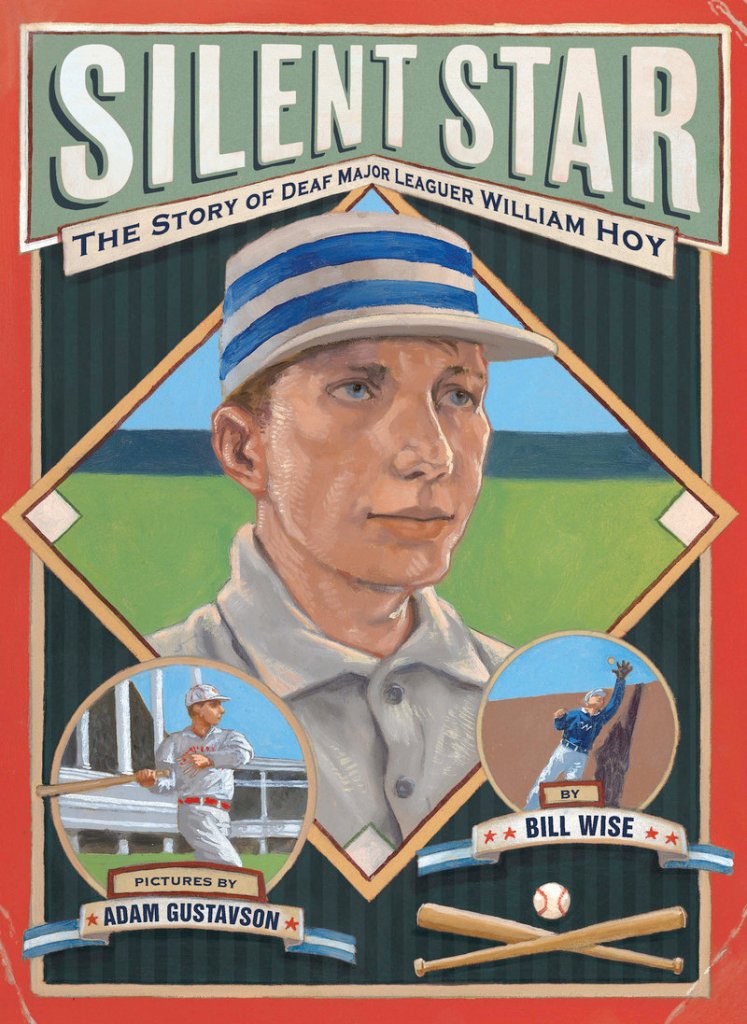

Hoy went on to have a long career in professional baseball, playing in major leagues from 1888 to 1902. His determination and success inspired Gorham writer Bill Wise to pen a children’s book about him, “Silent Star: The Story of Deaf Major Leaguer William Hoy” (Lee & Low Books, $18.95).

The book, which was illustrated by New Jersey artist Adam Gustavson, is Wise’s second book on a baseball player of the past. His first was about a Mainer: “Louis Sockalexis: Native American Baseball Pioneer.”

Wise, 54, teaches eighth-grade math and language arts, and writes during summer vacations and on weekends.

Q: How did you become interested in writing about old-time baseball players?

A: I’ve been a huge fan of baseball since I was a kid. I love the rich history, the great moments, the great players. Being someone who has lived my whole life in Maine, Sockalexis was always interesting to me. Both he and Hoy were inspirational people, people of great determination and great courage.

Q: How did you hear about Hoy, and what made you think he’d be a good book subject?

A: As a kid I remember hearing about him, but a few years ago, I decided I wanted to do some research and find out a little more about him. I found out that he was really an outstanding player who deserves to be in the Hall of Fame.

When you compare him to other people of his era, he definitely deserves it. (Hall of Famers from the 1800s) Hugh Duffy and Billy Hamilton had higher batting averages, but he compares to them in every other statistic.

And he was considered if not the best, one of the best, defensive outfielders of his day. When he retired, he was the record holder for total putouts and total chances.

Q: How did his hearing loss affect his playing?

A: When you’re playing outfield, you yell, “I’ve got it” to let other players know you’re going to make the catch. He had to have signals worked out with the other outfielders to communicate that.

When he was in the minor leagues, pitchers started quick-pitching him. He’d have to turn to the umpire to read his lips, to see if the pitch was a ball or a strike, and pitchers would quick-pitch him. So he worked out some signals with his third-base coach: Right hand up for a strike, left hand up for a ball.

Some people say the idea of umpires using hand signals began with Hoy, but hand signals weren’t used by umpires until about 25 years later.

Q: How did Hoy become a major league ball player?

A: He was from a very small town in Ohio, and he went to the Ohio School for the Deaf through high school. At that time, a lot of deaf young men were becoming cobblers, shoemakers, and that’s what he did. He ended up buying the shoe shop he worked in, and made a baseball diamond out back.

In the summer, in those days, a lot of people didn’t wear shoes, so it was a slow time and he’d play a lot of baseball. A barnstorming team came through his town, and the coach was just amazed by him. That led to him playing in the minor leagues, and then the major leagues.

Q: What are some of the other elements of Hoy’s story that appealed to you?

A: He was also very successful after baseball. He ran a 60-acre dairy farm in Cincinnati, then was the personnel director for Goodyear in Akron, Ohio. He was really inspirational in a lot of ways.

Staff Writer Ray Routhier can be contacted at 791-6454 or at: rrouthier@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.