Will Barnet threw his head back and laughed.

“Magic magic. That was a wonderful time in my life,” he said of his 50s. “You’re in good health. At 50, I was all over the country. Fifty was a very important time for me.”

Barnet relished turning 50, and enjoyed an additional half-century of a well-lived life. The prominent painter and artist died in November at age 101.

He tops a too-long list of prominent artists from Maine or with significant ties to Maine who died in 2012. That list also includes a young musician whose brilliant career was cut short by cancer, a carpenter-turned-poet who inspired youngsters to write, and an outspoken art critic.

Today, we pay tribute to them and remember that even though they are gone, the work that they left behind and the lives they touched along the way endure.

WILL BARNET, 101

BY AGE and accomplishment, Will Barnet lived as full a life as any of us could hope. That he died peacefully at home in his beloved New York City seemed somehow appropriate.

Barnet was born in Beverly, Mass., in May 1911. He studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston before moving to New York in 1931, determined with absolute certainty that he would make his life in the visual arts.

Over the next eight decades, Barnet exceeded his dreams.

He taught at the Art Students League in New York for many years, and at Cooper Union, Yale University and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. His works are in the collections of museums across the country.

In 2011, President Obama awarded him the National Medal of Arts, the highest honor for an individual artist in the United States. Before his death this year, France recognized him with the insignia of Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters.

Barnet lived in New York but spent his summers in Maine, and drew inspiration from his time on the coast of Maine. One of his most important series of work, which presented itself in paintings, drawings and prints, was based on a glimpse of his wife standing alone on their porch at dusk, her figure silhouetted against the sea. He called it “a moment to remember. I made a sketch of the scene and began a series of paintings of women and the sea.”

As much as people appreciated Barnet’s work, his friends and colleagues loved the man. He was gracious, generous and accommodating. He would discuss his art with anyone, and at every opportunity encouraged others to pursue their passions.

Barnet never stopped working. He was in a wheelchair in his later years, and painted from a seated position for as long as his energy sustained him. That amounted to about two hours a day, he told the Maine Sunday Telegram in July, during his annual summer trip to Phippsburg.

“It’s like life itself,” he said. “To be a painter and not paint is impossible. Painting is an inspiration.”

B.K.

HOWARD HOPKINS, 50

HOWARD HOPKINS may not have the most name recognition in Maine, but that is only because he wrote 31 Westerns under his pen name, Lance Howard.

Hopkins, who wrote more than 70 novels, died in January at age 50. His Westerns, which included “The Dark Riders,” “Pistolero” and “Coyote Deadly,” mixed Wild West action with modern issues, true-to-life characters and original storylines.

Hopkins wrote his first Western, “Blood on the Saddle,” in 1993. He wrote at home with books stacked floor to ceiling, and among posters of Captain America and Doc Savage.

Hopkins was also known for his children’s series, “Nightmare Club” and “The Chloe Files,” about a character derived from his novel “Grimm.”

B.K.

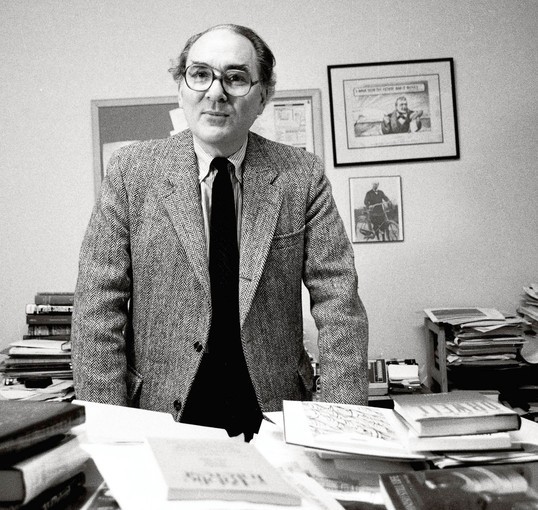

HILTON KRAMER, 84

HILTON KRAMER looked like an art critic is supposed to look — professorial with a perfect bow tie, bushy eyebrows and a head of wavy hair. His voice was weathered with authority, and when he used it, either in print or in person, the former chief art critic at The New York Times commanded attention.

He died in late March at age 84 in Harpswell.

Kramer became an art critic in the 1950s, and joined the Times in 1965. In addition to his tenure there, he was founding editor of The New Criterion magazine, a monthly journal that critiques the arts. He and his wife, Esta, began coming to Maine in the early 1960s, and bought a home on the midcoast in 1987.

Kramer had an international reputation, and did not suffer fools. In its obituary about Kramer, the Times cited the critic’s “imperious judgments” and uncompromising standards:

“He was a passionate defender of high art against the claims of popular culture and saw himself not simply as a critic offering informed opinion on this or that artist but also as a warrior upholding the values that made civilized life worthwhile.”

Dozier Bell, a midcoast Maine artist, knew Kramer personally and considered him a friend. She admired him on many levels, personally and professionally, and always learned something when she read his column.

“His impressive erudition came across with remarkable clarity, style and often humor, making his summaries of the art historical precedents and contemporary art world context for a given show a welcome educational opportunity,” she told the Portland Press Herald after Kramer’s death.

“That alone might have been enough to make me keep reading him. But it was his insistence on art as a worthy and serious spiritual endeavor, a way of connecting to who and what we are, that sold me on his criteria and got me enthusiastic about being an artist again.”

B.K.

NICK CURRAN, 35

WHEN HE was just a teenager, Nick Curran was already turning heads among Maine musicians with his dynamic guitar playing and singing.

By the time he was 19, Curran had left his home in Sanford for Austin, Texas, where he began touring with rockabilly veteran Ronnie Dawson. He spent much of his career in Austin, a hot-bed of the Americana and roots-based music that Curran so deeply loved.

Curran was just 35 when he died in October after a three-year battle with oral cancer.

Curran played in a band headed by his father, Mike Curran & The Tremors, as a teen before heading to Texas. After his stint with Dawson, he toured and recorded with rockabilly singer Kim Lenz.

He was a member of several bands, including the well-known blues-rock group The Fabulous Thunderbirds, from 2004 to 2007, and performed four songs for the HBO TV series “True Blood” in 2008.

Longtime Portland musician Matthew Robbins of King Memphis remembered Curran as someone whose talent and ability to learn were evident right away.

“Nick was like a sponge. He could see someone play something and play it right back,” Robbins told the Press Herald at the time of Curran’s death. “He was pretty amazing.”

R.R.

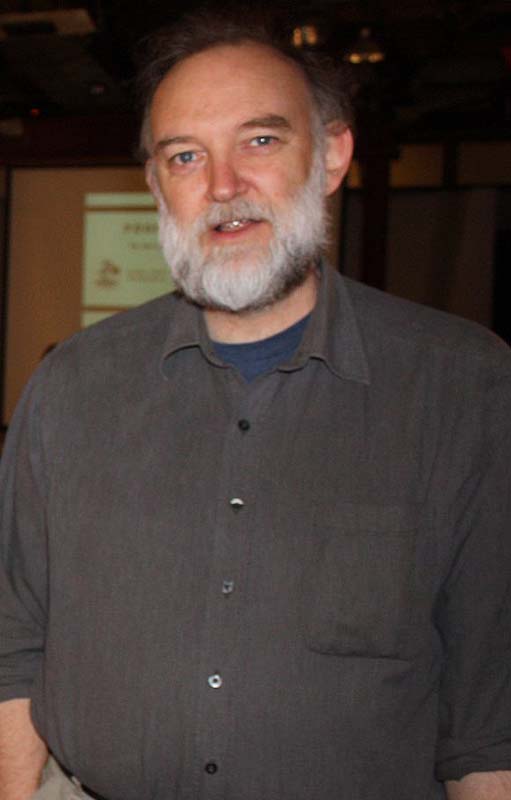

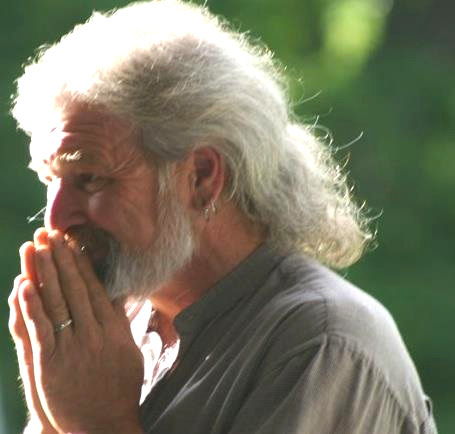

RUSSELL LIBBY, 56

MOST PEOPLE knew Russell Libby for his work as executive director of the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, or MOFGA. And well they should: Libby and MOFGA became such institutions in Maine that Gov. Paul LePage ordered flags flown at half-staff following Libby’s death from cancer at age 56 in December.

Libby was much more than a farmer, activist and farm advocate, though. He also was a writer — a poet, to be precise.

“Libby was an iconoclast,” wrote Joshua Bodwell, executive director of the Maine Writers and Publishers Alliance. “Not many poets can claim to having their poetry published in FEDCO Seeds Catalog, but there it is on the acknowledgments page of Libby’s 2007 collection, ‘Balance: A Late Pastoral.’ “

In that collection, Libby wrote, somewhat prophetically, the following:

“My last breath will still carry hope

for the future,

and love for the present, and you,

though many dark days may yet pass.”

Gary Lawless of Gulf of Maine Books of Brunswick published that collection. In his blog, Lawless wrote of his last reading with Libby at the Common Ground Country Fair at Unity in September.

“This year a scheduling error put Russell in two places at once, but at the last minute, he decided that we should read together, saying that he would do it because he really wanted to do it,” Lawless wrote. “His body was weak, his vocals were diminished, but his voice, his voice was still strong, his spirit, his grace.

Will the apples miss him now,

will the bees?

Will the hayfields know he’s gone,

will the trees?

We love you Russell. Thank you. Travel well.”

B.K.

MICHAEL MACKLIN, 62

IN MAY, the Waynflete School mourned the death of Michael Macklin, a beloved poetry teacher who died at age 62 while on a trip with students to the New England Young Writers Conference in Vermont.

Waynflete hired Macklin in 1997 to work in the school’s facilities department. His interaction with students inspired him to pursue his own writing. At age 50, he returned to college and earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in creative writing at the Vermont College of Fine Arts.

Soon after, he began teaching poetry, and served as a mentor to hundreds of students.

“Wherever he was, when he walked away, he walked away as a friend,” said Peter Piattoni, a family friend. “He always left having met a new friend.”

Joshua Bodwell, executive director of the Maine Writers and Publishers Alliance, memorialized Macklin in an Alliance newsletter.

“One of the first times I ever met Michael, a couple dozen people had gathered in Biddeford for an intimate reading during National Poetry Month,” he wrote. “In what I would soon discover was his typically egoless self, Michael began his reading not with his own poems but by sharing poems he loved by other poets. He read Adrienne Rich, and then he read Phillip Levine’s masterful ‘What Work Is,’ one of my favorite poems of all time, and that’s how I’ll always remember him: there in that small room, sharing his love.”

B.K.

THOMAS CORNELL, 75

THOMAS CORNELL, a nationally known artist and longtime art professor at Bowdoin College, died at age 75 in December after a long battle with cancer.

Cornell began his career at Bowdoin in 1962, and established the college’s visual arts program. He worked his way up from assistant professor and associate professor, and was named a full professor in 1975.

In 2001, Cornell became the Richard E. Steele professor of studio art. He was named the Richard E. Steele artist-in-residence in 2008, and retired this past June.

Cornell’s legacy in the visual arts extends far beyond Bowdoin and Maine.

He was an early member of the Union of Maine Visual Artists, and had about 30 solo exhibitions and more than 100 group exhibitions throughout his career. The New York Times reviewed his work, and his art was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, the National Museum of American Art, in Paris and elsewhere.

His final show as a living artist was held this past summer at Aucocisco Galleries in Portland.

B.K.

SONNY GOOGINS, 72

CARROLL “SONNY” GOOGINS shared his passion for music with students at Brunswick High School for 40 years.

He also shared that passion by playing piano for Maine theater productions and by serving as music director for more than a dozen musicals at Portland Players and Portland Lyric Theater in South Portland.

Googins died in June at age 72 after a long battle with Alzheimer’s disease.

In the 1970s, Googins was active in the Brunswick Music Theater, now known as Maine State Music Theater, playing piano in the orchestra. At Brunswick High School, he taught music theory, music history, music fundamentals and choir.

“Music was in his blood,” Ron Trell, Googins’ longtime domestic partner, told the Press Herald after Googins’ death. “Every day of our 43 years together, there was music. Usually, it was him at the piano. It was beautiful, absolutely beautiful.”

R.R.

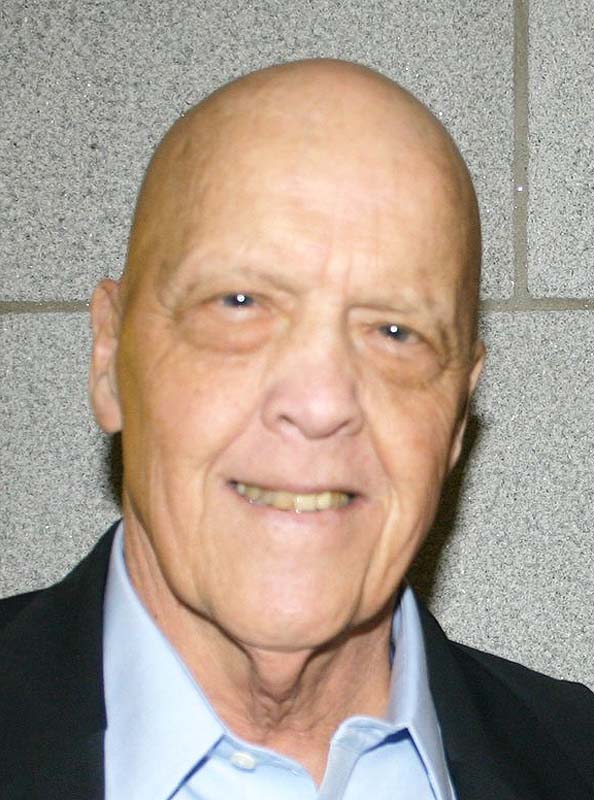

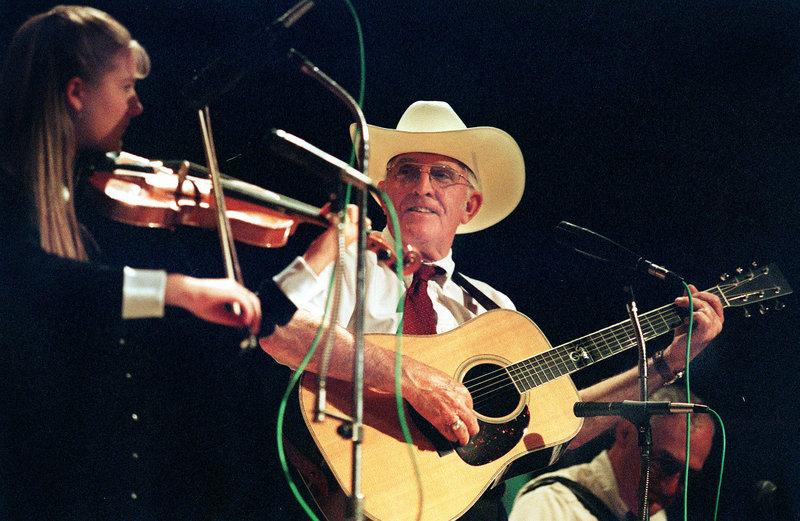

MAC McHALE, 80

ALLAN “MAC” McHALE grew up in Bangor with one ear glued to the radio. In the 1930s and ’40s, he loved listening to the country music of local performers such as Hal Lone Pine and Gene Hooper.

McHale went on to play old-time country music himself for some 60 years, both in Maine and around the country. He was still performing in November when he suffered a heart attack, which led to his death at age 80.

McHale started playing banjo at 18, and also played guitar and mandolin. In the 1960s, he played throughout New England with the Larkin Hill Singers.

In the late 1970s, he started a band called Northeast Winds with longtime friends Emery Hutchins and Paula McHugh. That band lasted 18 years, and played traditional Irish music all over the eastern U.S.

McHale formed the Old Time Radio Gang in 1986, playing the country music of his youth.

His final performance was at the Bangor Grange Hall — the same place where his music career started.

R.R.

RICHARD LAWLOR, 59

IN THE LATE 1990S, drag shows were hardly mainstream culture in Portland. Thanks to Richard Lawlor, they are well on their way to becoming that now.

Lawlor, who lived in Portland for most of his life, died in October at age 59.

He may have been better known for his work with the Maine Festival, New Year’s Portland and concert series at Congress Square. But his passion was Portland’s drag culture, said his friend, Chris Busby.

“Richard’s work many years ago organizing drag shows was key to emergence of the scene. He laid the groundwork for those sorts of troupes to become popular today,” said Busby. “Back then, it wasn’t nearly as easy to find venues for these sort of performances. He had to win some people over that way.

“Within the drag community, there are strong personalities. The scene could be fractured. He was able to negotiate all of that and get everyone on the same page.”

Lawlor was active in the local gay community in other ways as well. He published and edited “The Companion,” which covered news and entertainment in Portland’s gay community, and began a website about gay nightlife in Portland.

B.K.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Staff Writer Ray Routhier can be contacted at 791-6454 or:

rrouthier@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.