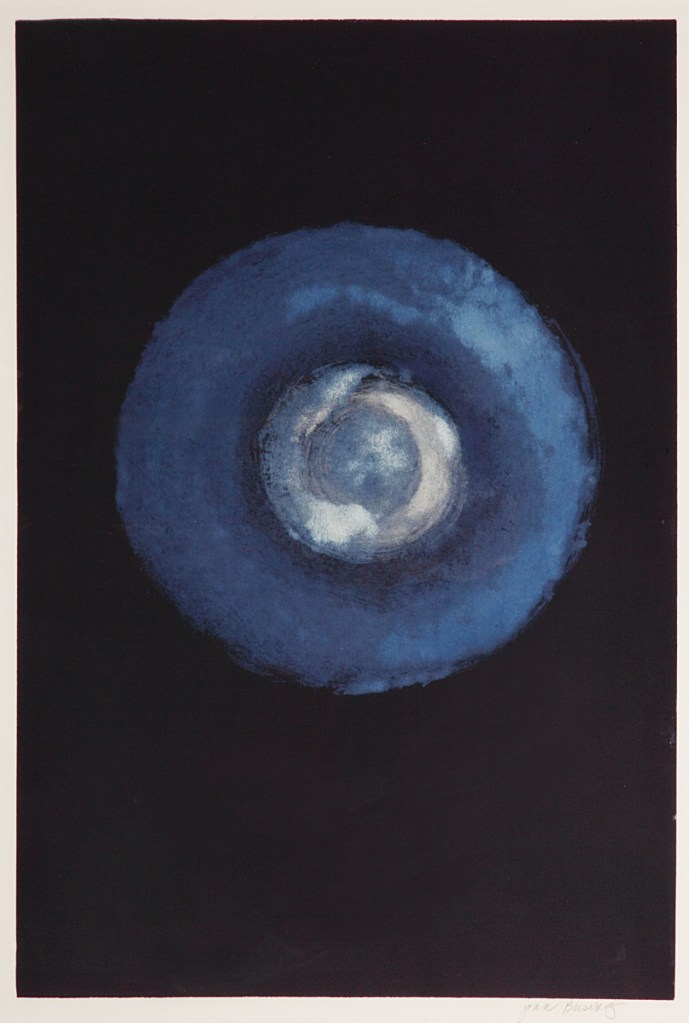

The two solo exhibitions now on view (but soon ending) at the Maine Jewish Museum are connected with astonishing directness: Virtually all of the works by both artists feature a single circle. Joan Busing’s works are monoprints of full moons. Sara Crisp’s works are encaustic paintings based on Eastern sacred geometry, and many feature inclusions from the natural world, such as bird bones, leaves or insect wings. Based on a circular form on a square panel, they are mandalas.

That both artists work with the circle has a resonating effect that forces the viewer to really think about the circle as a thing in painting. And, yes, it is a thing. In some ways, it could be seen as the most truly basic issue of painting: The circle can be seen as a face, maybe, but it is as a figure on a ground that is ground zero for Western painting. “Squaring the circle” goes back thousands of years: It’s a geometrical challenge to create a square with the same area as a circle with only a compass and a straightedge in as few steps as possible. A mandala is a Hindu or Buddhist representation of the universe. It is a spiritual symbol and often used for meditation. Not all mandalas have a circular structure, but that is the most recognizable format. When I say Crisp’s panels are mandalas, I mean they clearly can be used for meditation. They are beautiful objects and succeed as paintings, but the works themselves make a strong argument for spiritual practice.

As a group, these circles on rectangular or square supports have the feel of fine craft akin to, for example, the vessel tradition. Some art fans might look down on fine craft as bereft of content, but that’s just laziness posing as snobbery. Most craft doesn’t rise to the level of “art,” but let’s be honest, most painting doesn’t either – it is kitsch. And while painting is my thing, I contend that fine craft, which requires skill as well as refined technique, has a much better batting average for success than painting. What we’re talking about here are Crisp’s exquisitely crafted wax paintings and Busing’s repetitions of the same structure with some variation. When Busing’s work succeeds, it does so on the strength of the materials, their colors and variations in textures. And because the work is printed, it relies on a mechanical technique for its textures. (Monotypes are paintings made on glass or plexi and then printed once – or sometimes twice – on paper. Monoprints are unique prints; they might include a monotype, but then typically something is painted by hand or printed separately with a matrix or stamp. Busing identifies her works as monoprints.)

“Red Moon,” by Joan Busing.

As craft, the work of both artists hails its relations to their repeated forms as well as to its own craftsmanship. This is particularly effective for Crisp because her sense of detail and rich (and ritualized) use of the ancient wax medium sets her work apart from other mandalas, Celtic patterns, Arabic design, Christian stained-glass and illuminated manuscript decoration and so on, while expanding her content.

Crisp returns repeatedly to an overlapping circles grid (e.g., the “flower of life”) so that it forms something like her baseline, however complex and detailed. And she isn’t afraid of showing her work in groups which, for the smaller squares in particular, makes them appear almost irresistibly as Persian tiles.

While Crisp invites broad and widely shared references, what underlies her imagery is not the hypothetical machinations of geometry, but the natural world and its actual mathematical systems. Crisp will make a circle of bird bones – and it’s beautiful. Sometimes she simply includes natural objects in uncolored encaustic (largely beeswax, its default color is organic white) like a pair of dandelions or dragonfly wings. But for the most part, she maintains the circle as her mantra. After a while (and it’s easy to get lost in Crisp’s paintings for a long while), the logic of the work shifts from being circle-based to meditations on the fundamental geometrical order of the natural world. We start to see leaf logic proliferating among the work. One of my favorite of her pieces, for example, features a chunk of real lichen standing out from a background painted with stylized leafy small plants … or they might be real. Whichever it is, the feel of ancient decorative painting is uncanny – like what you would find in an ancient Roman house. (And the Romans, by the way, painted their bronze copies of Greek sculptures with encaustic – which must have been freaky in its organic realism.)

Untitled, by Sara Crisp.

Crisp’s most impressive work is an outlier. To be sure, it’s a circle on a square panel. But it’s very large and velvet green so dark it looks black. And the circle is represented as a sphere covered in tiny circles (not unlike a beaded bead). It’s quiet and subtle but visually rich. It’s like a luxurious armchair for your eyes.

The common quality of the simple circle on a square in painting is spiritual, whether we’re talking about mandalas or Malevich. And that is the shared space of Crisp’s and Busing’s handsome and thoughtful work.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.