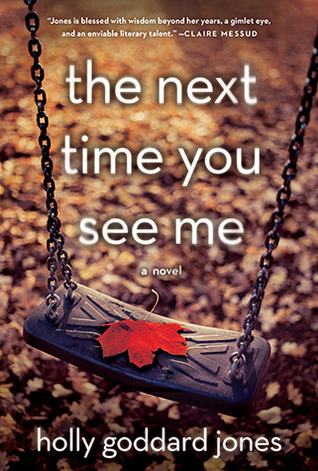

The small-town setting of “The Next Time You See Me,” Holly Goddard Jones’ debut novel, is no place for the faint of heart. The more we see of the people who live here, the easier it is to understand what one character means when he says it’s best to lay low and live “a small life, a sad life.”

Especially if you’re different. Because Roma, Ky., circa 1993, is a place where cruelty is “the way of the world” and kindness “an anomaly.” Where taunts and pranks aren’t limited to the schoolyard, and no one is “too old to be bullied … too old to need a rescuer.” Jones, who grew up in Russellville, knows this town all too well.

Roma is the fictional factory hub — “neither a bad place nor a nice place” — that Jones wrote about in her first book. A taut, shimmering short-story collection called “Girl Trouble” (2009), it captured a generation of young women and the dangers they faced growing up: predatory teachers, teen pregnancies, romantic triangles and violence at the hands of young men.

Jones brings some of those same themes and emotional depth to “The Next Time You See Me,” a densely populated literary thriller that begins when a hard-drinking, bar-hopping local woman named Ronnie Eastman disappears, and her body is found in the woods by a 13-year-old girl who decides to tell no one.

Within weeks, the search for the missing woman touches everyone in her tightly knit community. Rotating between multiple points of view, Jones unveils an intricate network that connects them all. Among them are Emily, the young girl who finds the body; Christopher, the new boy in Emily’s class and object of her helpless crush; Susanna Mitchell, the dead woman’s sister; Tony Joyce, the detective assigned to the case; and Wyatt Powell, the hapless factory schlub whose encounter with Ronnie may have been her last.

Ostensibly a murder mystery, “The Next Time You See Me” steers clear of the standards associated with the genre. No crackerjack detective or brilliant amateur sleuth appears at the crime scene. No coldblooded psycho lurks “out there” waiting to kill again. The new cop assigned to the case has yet to even use his gun.

Nevertheless, the story that slowly unfolds, as we peer into these lonely lives, is as suspenseful as any mystery. What drives it isn’t what happened to Ronnie; it’s how it happened and what happens to everyone as a result. It’s a story of how a small-town mentality can contribute to an untold number of small disappearances, and Jones skillfully catalogs the combination of casual cruelty, conformity and fears that make those possible.

Susanna, the product of an abusive home, decides against a risky boyfriend and makes a safer choice, only to realize 15 years into her marriage that they’re “settling into a lifetime of unkindness toward one another.” Her sister’s disappearance offers a chance to resurrect a crush from high school that all too briefly provided “the most romantic moment of her life.” Introspective, troubled Emily should be daydreaming about a boy other than the one who once helped her with a school project — he’s become a bully and her worst enemy. But as she wanders the woods behind her suburban back yard, a chance to win him back beckons: She has a better experiment he should find irresistible.

Detective Joyce, his minor-league baseball career cut short by a back injury, has returned to Roma to face the same outsider role he played growing up there, “black in a white town and a white sport.” It’s different now, but he knows that even if he runs for sheriff, “it would be high school all over again.” Then there’s 50-ish, overweight Wyatt, the butt of his co-workers’ jokes. After years of trying to fit in, Wyatt is pretty sure he’s gone “too long in loneliness, too long in disappointment” to hope for anything better — any true shot at happiness might practically kill him.

More damning than hours of cruelty or bullying are times when neither make a difference, when invisibility does the job. After a heartbreaking chapter in which Ronnie describes the loss of the one hope she held out for love, it’s not hard to see the real killer in Roma — compassion, which the characters lunge at like starving animals. In an environment where everyone’s heart seems to be made of cement, the kindness that springs up between the cracks triggers an almost unbearable yearning. For all its futility, the world of “The Next Time You See Me” is never entirely dark. Like Emily’s watch over her gruesome secret science project in the woods, — “each day it was different — scary, yes,” but it makes her feel “fully alive” — Jones’ steady gaze at her fictional universe lays bare a similar metamorphosis, in which the worst that could happen might even be for the best.

Send questions/comments to the editors.