While we tend to focus on the comings and goings of art exhibitions, even at museums, one of the reasons the word “museum” resonates with such authority is the sense of permanence. With galleries, what goes up must come down. With museums, what goes in should never come out.

And unlike museums, galleries themselves tend to come and go – always a painful process, largely because we come to know and love the venues we visit but haven’t yet connected with the new ones.

It’s easy for me to lament, for example, that Pho Pa Gallery in Portland is now mounting its last show. It’s been one of the Portland area’s best galleries for the past few years, and I have found many of their shows worth reviewing. It’s harder to explain my growing appreciation for Portland’s Able Baker Contemporary and Speedwell Projects, Cape Elizabeth’s Ocean House and Rachel Walls Fine Art, or Brunswick’s Frank Borofsky Gallery and its reboot under director/painter Mark Little. And then there are the new venues I haven’t yet visited, such as Portland’s Border Patrol and others around the state. I was able to get to the pleasantly impressive reboot of Joel LeVasseur’s Backroads Gallery, which I will discuss later. First, an exciting permanent addition to the Maine art scene – appropriately, at a museum – needs acknowledgment.

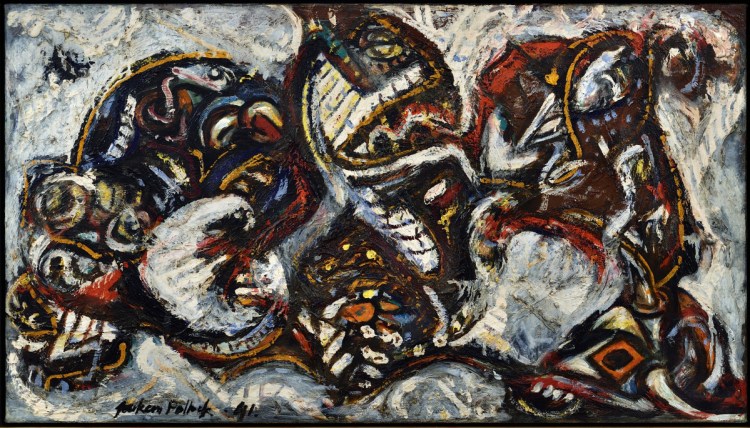

The most impressive step forward in Maine so far this summer is the acquisition of a single painting by the Colby College Museum of Art as part of its incredible Lunder Collection: Jackson Pollock’s 1941 “Composition with Masked Forms.”

In short, Pollock is arguably America’s most consequential painter and “Composition with Masked Forms,” a work that long remained out of sight in a private collection, is one of his most critical pieces. I think it is not only one of Pollock’s best works, but that there may be no work of art that does more to unpack Western culture’s shift from European to American painting.

“Composition with Masked Forms” is a horizontal painting just over 4 feet wide. It features the swirling forms of Inuit and Tlingit (Native Americans of the Northwest) masks. While the white background might appear like fog in print or on a screen, it is materially substantial in person. In fact, the work’s physical build-up of paint is what truly propels its energy, more even than the imagery. The substance and energy of the paint are applied with such force and ability – almost in writhing currents – that I can think of no work that makes a better argument for Pollock as a painter. His mature works, the ones that have sold for upwards of $200 million, were largely made in his famous “drip” style: He would dip sticks into buckets of paint and drip it onto his canvases laid out on the floor.

Formally, Pollock’s mature works accomplish several things at once: They get beyond the figure/ground distinction (to see a figure, it has to stand out from the background), they free lines from the job of describing shapes, and the paintings achieve the idea of the “allover” composition, rather than a balance of this shape against that, etc.

“Composition with Mask Forms” touches on all of these subjects. With its roiling rhythms, interaction of positive and negative space and built-up physicality of the paint, Pollock has come far in dissolving the figure/ground distinction. Some of the lines in the painting describe shape and make recognizable forms, but not all. Many of the dark and white lines are more dedicated to enforcing the swirling sensation: They are more about motion and rhythm than shape. And finally, the sense of the allover bubbles up through the ever-churning energy and physicality of the surface. There is a sense of margin, but as surprising as it sounds, we see this in the majority of Pollock’s later works as well.

In terms of content, Colby’s excellent label copy connects “Composition with Mask Forms” to both Picasso and André Masson. The connection to Picasso follows his Cubist-era focus on masks as well as later mirror paintings. Masson, on the other hand, was the consummate Surrealist, the official definition of which was “automatic writing” as opposed to the scripted alternative reality of Salvador Dali or René Magritte. This connection to authentic surrealist practice blends extremely well with Pollock’s interest in Jungian psychology with its focus on the unconscious mind and archetypes.

Masks, of course, are a great marker for the Jungian archetypes. They also find shared space with the “Indian Space” painting movement that had been growing in New York since the 1930s, a connection that has not been sufficiently examined.

Another under-investigated connector is the fact that Pollock went to see the Mexican artist José Clemente Orozco as he was painting “The Epic of American Civilization,” a seminal mural series in what we now know as the “Orozco Room” in Darmouth College’s Baker Library.

Whatever the specifics of his inspiration, it’s clear Pollock was hardly operating in a void. But what matters most is where Pollock took his painting practice, since the current American myth of art (which only came about after WWII) generally follows precisely what Pollock was up to with “Composition with Mask Forms,” which is the common understanding of Abstract Expressionism: The artist wrestles with the materials to express their own inspired thoughts, unconscious and otherwise, and establishes authenticity from the extent to which the ideas and feelings are personal and original to the artist.

To be sure, this is a flawed model, but it’s pervasive in America among both artists and the public.

“Vacationland,” by Joel LeVasseur

However difficult he was as a person, I consider Pollock to be one of the 20th century’s greatest and most influential artists. And, frankly, I would rather have a great turning-point painting like “Composition with Masks” in Maine over just about any major drip painting. It might not have the aura and scale of Pollock’s most iconic works, but it offers far more in terms of mystery, content and Pollock’s personal presence as an artist. Its presence is a coup for Colby and the people of Maine.

BACKROADS GALLERY is a different kind of reboot. The Damariscotta gallery run by painter Joel LeVasseur has re-opened after nine years. It’s a small space off the beaten track (albeit a particularly picturesque part of the world), but the quality of group show there featuring 11 invited artists is excellent, most notably the work of LeVasseur, Alex Rheault, Rachael Eastman, Joan Freiman, John David O’Shaughnessy and co-curator Krisanne Baker.

The charming grounds expand the scale of the gallery and provide an excellent setting for the steel sculptures of Duncan Halm. Visiting, I was charmed, pleased and impressed.

In many ways, the petite gallery could hardly be more different than the Colby Museum of Art, the largest college museum in America, but they are both reminders that even in these (politically degraded) times, good things are taking root as well, small and large.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.