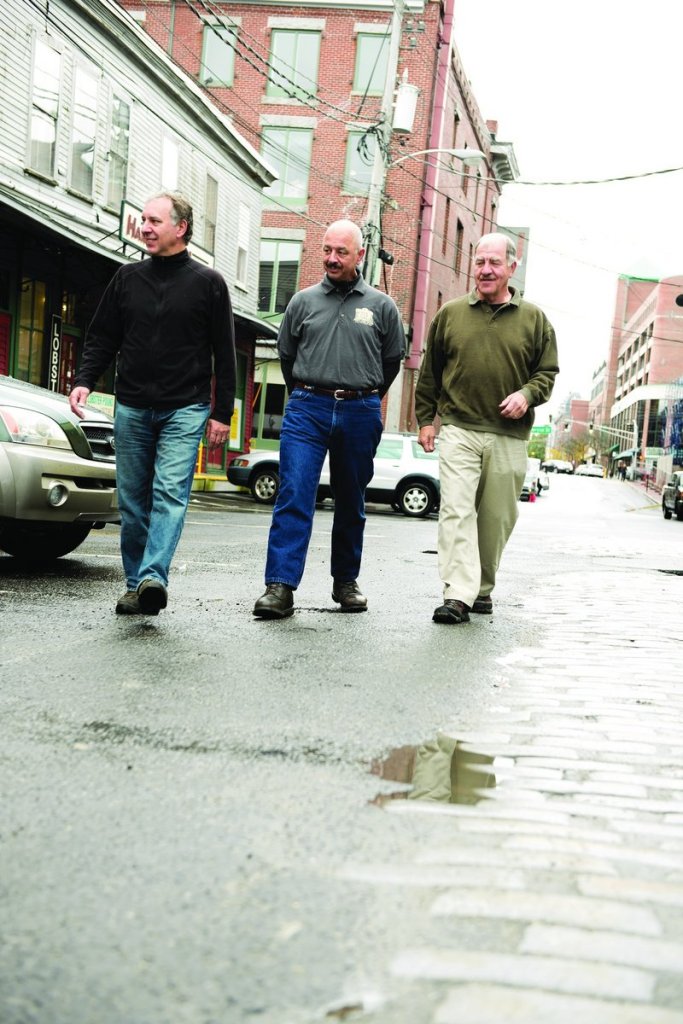

Nick Alfiero, one of the three brothers who own Portland’s Harbor Fish Market, says that whenever anybody talks about their 47-year-old family business these days, they always throw out the word “iconic.”

How does that make him feel? Good, right?

“Old,” he said with a wry smile. “Old, to tell you the truth.”

If you don’t know Harbor Fish and its (sorry, Nick) iconic red storefront on Custom House Wharf, you either don’t like seafood or you’ve been living under a big Maine granite rock.

Nick, Ben and Mike Alfiero are the fishmongers who are responsible for mussels being on practically every restaurant menu in Portland.

And if you’ve ever tucked a couple of live lobsters underneath your airplane seat, you have the brothers to thank. They helped design the box.

The front of their store has been photographed and painted so many times that in the mid-1990s they had the image trademarked.

Julia Child visited once, and celebrities from Billy Joel to Patrick Dempsey have stopped by to purchase seafood.

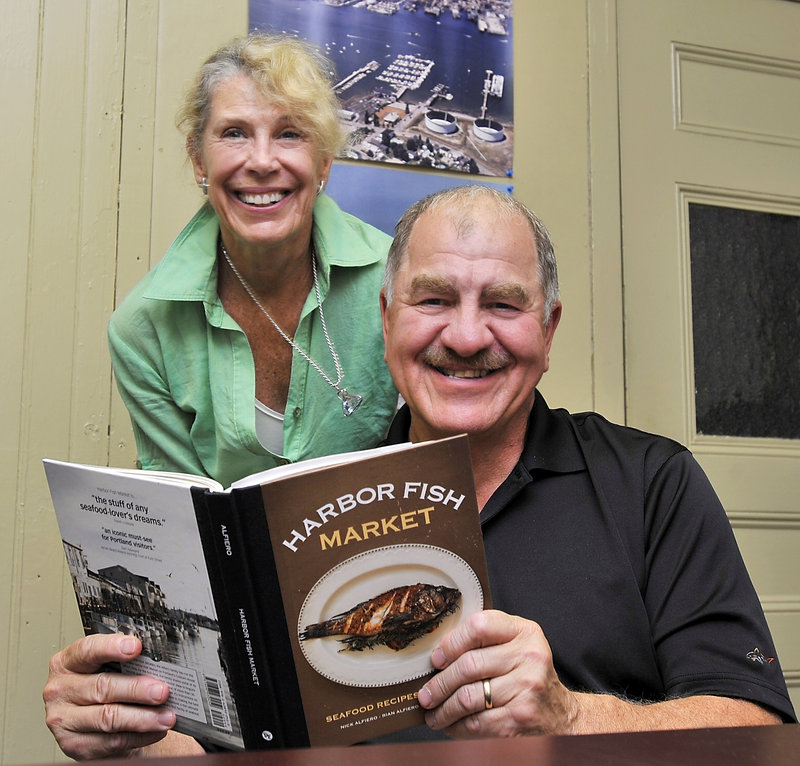

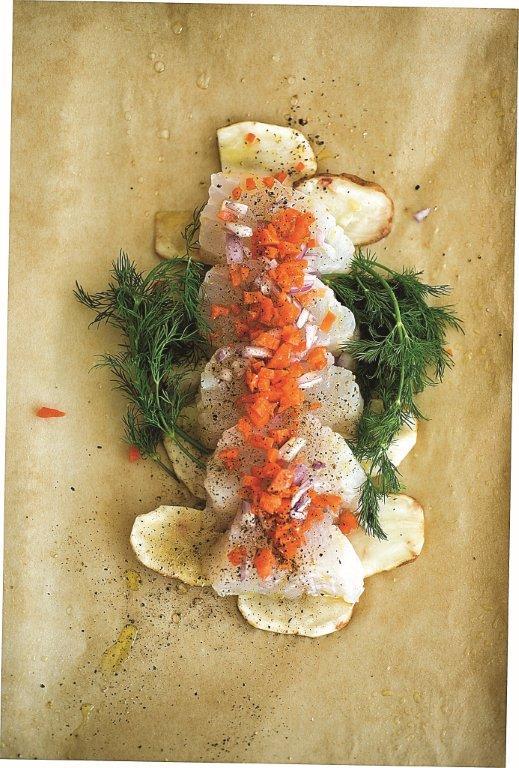

Now the Alfieros have published their first cookbook, titled simply, “Harbor Fish Market” (Down East Books, $29.99). It is filled with tips on buying, storing and cooking seafood, but also with recipes like Nick’s lobster shortcake, which he is convinced is going to be the next big thing.

Everyone in the big Italian family loves to cook and eat, but they rarely follow recipes themselves.

“We’ve had relatives and friends forever say, ‘How did you do that?’ ” Kathleen Alfiero said of her husband Nick’s creations in the kitchen. “And he says, ‘I don’t know.’ They think he’s just being secretive, but he never made the same (recipe) twice.”

To record his family’s favorite dishes for the book, Nick Alfiero cooked every day for six months, with Kathleen sitting at the counter documenting everything he did on a computer. (When it came time for photos, he churned out 27 recipes in just three days.)

“We tried to make a good balance of stuff,” Nick Alfiero said. “We tried to keep them simple. I didn’t want to go into 38 different ingredients, because most people I know work and don’t have time, except on weekends maybe, to develop stuff.”

‘PACE LIKE NO OTHER’

At the fish market, Alfiero and his brothers work in close quarters out of a small, paper-strewn office where Nick takes or makes at least 200 phone calls a day, just steps away from the lobster tanks and the branzini, black sea bass, ocean perch, flounder and other fish chilling on beds of ice.

Selling fish from the Gulf of Maine is different from a farmer selling produce, Alfiero says. A farmer knows how much lettuce there is in his field, but who knows how much fish a boat will catch on any given day?

“On a typical day, I might be pushing hard to sell cod, or pulling in because there’s no cod coming,” he said. “It’s sort of like the stock market, in a way. The pace is like no other. Every day is different.”

On the market floor, Alfiero points to two posts about 20 feet apart and says that was the sum total of the original store his father and uncle started in 1966.

“We cut fish back there,” he said, pointing to the back of the market. “There was a lobster tank over there. It was an old wooden tank that had glass in it.”

Spending time with Alfiero and his family is like getting a firsthand lesson in Portland history.

Ben Alfiero Sr. took over control of the family business from his brother John in 1969. At the time, his only experience in the seafood industry had been lumping fish — unloading them off of boats on the waterfront.

Ben Alfiero Sr. also owned Pine Tree Paper Co., which was located where Spread restaurant is now, and his brothers owned a meat market on India Street, where Coffee By Design is now located.

Nick was 16 at the time and already going out with Kathleen. Ben was 10 or 11, and Mike was 6.

“Me and some friends would ride our bikes down here, we were 10 or 11 years old, and we would hang out back and catch eels,” Mike Alfiero said. “Then my uncle and my dad would put us to work for two or three hours sweeping whatever, and we’d get five or six bucks at the end of the day.”

Eventually, Ben Sr. fell in love with the business, and he started trying to convince Nick, who had left Maine for a corporate job that kept him moving around, to come home and help him run it.

So, in 1976, Nick and Kathleen left New York City and returned to Maine.

As Nick puts it: “Gray suit, briefcase. Back to boots and mud and fish guts.”

The Alfiero brothers say that if you work in seafood long enough, immersed in what Mike calls “the wetness, the fishiness, the smells, the culture in and around it,” it all becomes second nature.

Even the stink.

Nick remembers going into a Falmouth record store a year after he moved back to Maine. He had just come from work.

“I walk in the store and I’m kind of flipping through the vinyl, and the next thing you know this big golden retriever comes up, and he’s starting to lick my shoes, and he’s licking my leg and he’s smelling me and I know what it is,” he recalled. “So I kind of push him away. The next thing I know, I hear the owner — it was a couple — I hear the woman say ‘Jim! I’ve told you a hundred times to clean that dog. It stinks like crazy.’

“I’m standing there going, ‘Oh, no.’ “

Alfiero turned around and walked out the door. He said the experience taught him a lesson about changing clothes before going out in public.

‘GRITTY WAS 40 YEARS AGO’

Back then, the Portland waterfront was a seamy place that could be a little scary. There were none of the little boutiques, tony shops and fine dining restaurants that fill the Old Port today. Harbor Fish saw its share of shady characters wander in the door off the rough-and-tumble streets.

“I remember people walking in here and they’d open up their coats and have all kinds of things you could buy,” Kathleen Alfiero said, laughing.

“Guys were fencing stuff,” her husband added. “You know when they say ‘the gritty waterfront?’ This isn’t gritty. Gritty was 40 years ago. It was very colorful.”

Nick recalls his Uncle John as a big, burly guy, hard drinking, married five times, and “waterfront smart.”

“He befriended all of the wrestlers who used to come down to the Portland Expo,” Alfiero said. “They had wrestling and boxing every week, and he knew them all. They would come in and he would flip over 15 wooden boxes (filled with fish) out back and he would start cooking lobsters and they’d all sit around. Big guys.

“At the end of it, this guy would pass my uncle a wad of green bills, like, thanks, you know, and here’s some tickets to tonight’s show.”

One story in the new cookbook is likely to make both environmentalists and sushi lovers gasp in horror. In 1969, two brothers came into the market with two bluefin tunas they had harpooned offshore, weighing 500 to 600 pounds each. John Alfiero told them he couldn’t sell that much tuna, but he would cut them into steaks and get what he could for them.

“Now, no one else anywhere in this country probably sold tuna,” Nick said. “No one knew what tuna was.”

The market ended up selling about 400 tuna steaks from one of the fish. The price? Three pounds for a dollar. In today’s market, because the bluefin tuna population has been so depleted, that one fish probably would have gone for at least $15,000.

“You don’t want to know what we sold the toro for — the fatty toro, which today would be worth a fortune,” Mike Alfiero said. “We were selling it for, like, 59 cents a pound or something.”

What happened to the other fish? They had to throw it away, and it became chicken feed.

When he hears a groan, Nick adds, “I know. But to sell 400 pounds of tuna steaks in Portland in those days was a huge accomplishment, even at 3 pounds for a buck.”

TASTES, AND TIMES, HAVE CHANGED

The Alfieros have seen many trends come and go, in both public tastes and in what restaurants want to put on the plate.

“In the early days it was a few species,” Nick said. “It was haddock, lobsters, clams, lobster meat, a few basic things at that time. There might have been Atlantic salmon at a certain time of year — there was no farm-raised salmon — so the consumer, when they came into the store, really only had 10 or 12 choices. So we started searching out other things, outside of the local area, to bring in.”

Restaurants started asking for fish from Florida or the West Coast, and for more exotic things, like flying fish from Tasmania.

“From a restaurant’s perspective, they are constantly searching for new ideas — a new trend to follow or create,” Mike Alfiero said. “The public sort of follows that, and the public in the Portland area certainly has become more knowledgeable around the different foods and cuisines, seeking a little variety. But we’ve been responsible for a lot of that, too. I feel like our operation here, we were way ahead of the curve. We were marketing fresh squid and mussels and all of the things that have become popular, and we were doing it years ago.”

“That was our calling card with a lot of restaurants in the very beginning,” he said. “We were doing things that our competitors were not.”

Mike remembers buying wild-harvested mussels from Chebeague Island back in the mid- to late-1970s.

“They were big, barnacles still on them, and they were beautiful,” he said. “And people were like, ‘Wow, geez, mussels? We don’t eat mussels.’ But little by little, we developed a following of people who wanted to eat them. Now you look at the mussel industry, and they’re in every restaurant. It’s become almost like a commodity.”

Today, the emphasis on local foods has refocused restaurants’ interest in things like Maine oysters, which Mike Alfiero said is today’s version of the mussel. Harbor Fish now brings in an average of 20 varieties of Maine oysters a week.

What’s the next big thing in local seafood? The brothers say it is alternatives to cod, haddock and other whitefish: hake, cusk and pollock. Some restaurants have already started serving hake and pollock, thanks to the high price of cod and haddock.

“All the big-name restaurants are doing it, but the public still isn’t buying it in quantity,” Nick said. “They’re still coming in after the haddock and the cod, which is fine, but we’re selling more hake and pollock than we ever have.”

Char is another tasty fish that restaurants are serving but the public isn’t yet buying. But Portlanders are making up for it in other ways.

“If you take canned tuna out of the equation, Portlanders eat on average 8 or 9 pounds of seafood a year,” Nick said, “and nationally it’s like a half a pound a year. So Portlanders eat an enormous amount of seafood compared to the rest of the country, and that’s including Florida and other coastal communities — Louisiana, California and Alaska.”

What about the Alfieros? Do they ever tire of eating fish?

Nick says he doesn’t eat beef anymore, and eats seafood three to four times a week. He chalks it up to the wide variety available at his fingertips. He usually grabs dinner on his way out the door.

“A clam digger will come in with some clams out of the Harraseeket and they’re nice and black and they’re beautiful, and the next thing you know I’m throwing three pounds in the back to take home,” he said. “When the shad roe first comes in and they’re beautiful, I’m scarfing those.”

Mike said his brother’s regular diet of seafood reflects the family’s longtime philosophy of not selling anything to their customers that they wouldn’t be comfortable eating themselves.

“It’s not just about selling and buying fish,” he said. “It’s about doing it with integrity and ethics.”

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Send questions/comments to the editors.