AUGUSTA — Gov. Paul LePage’s two major opponents in the 2014 governor’s race say they would nix the A-F school grading system if they are elected, casting doubt on the future of the program if LePage doesn’t return to office.

From the start, the report card system unveiled in May provoked backlash from educators, Democratic legislators and many parents, who said the grades were an unfair and incomplete depiction of school quality. That sentiment is shared by Democratic U.S. Rep. Mike Michaud and independent Eliot Cutler, who both say they will run for governor next year.

In an emailed statement, Michaud said the system is deeply flawed and undermines public schools.

“Like most people, I think it’s extremely important to hold schools accountable, but we need a better approach that includes parents, teachers and administrators,” Michaud said.

Cutler, who finished a close second to LePage in 2010, said that instead of school quality, the grades represent inequities in resources across the state, both in students’ homes and in the system of state aid for schools.

“It’s not clear to me where the A-F grading takes us,” Cutler said. “It tells us something we already know, and that is that our funding formula in Maine and our distribution of resources in Maine is problematic.”

When the grades were first released, staff at the Department of Education had to “hunker down” and ride out the criticism for a couple of weeks after the grades were released, but since then they’ve seen acceptance of the system, spokeswoman Samantha Warren said in July.

“Very quickly the conversation shifted from, ‘Should they be doing these grades?’ to ‘What do we include in these grades?’ to ‘What do we do about these grades?'” she said. “Now schools are in a position to engage with us in a conversation about what this was all about.”

Questions raised nationally

On the national scene, however, a new round of debate has erupted about the validity and usefulness of A-F grading for schools, which could affect the drive to implement it in more states. And without a place in statute or federally mandated reporting, Maine’s system could be vulnerable to changes in the political environment in Augusta.

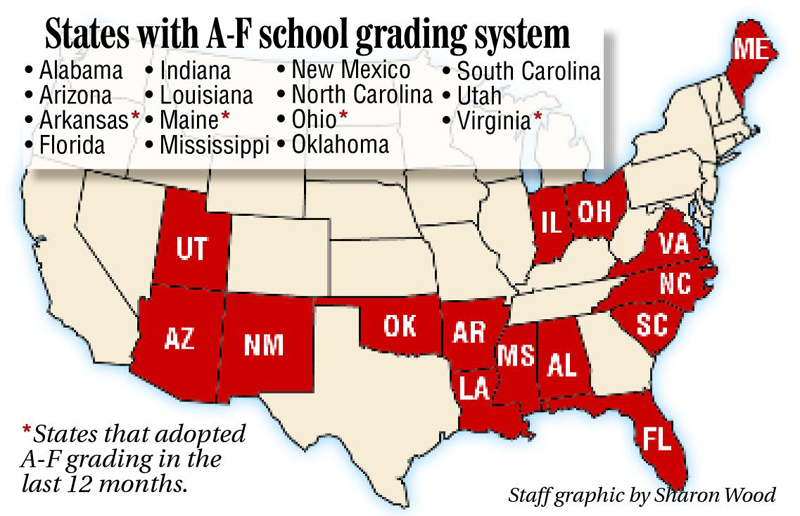

There are 15 states with A-F grading for schools, with Maine as one of four states to join the trend just in the last year. Maine’s system is far less entrenched than the others, and not just because of its newness.

In most states, the systems were adopted through legislation, but Maine’s is an initiative of the LePage administration. There’s nothing in statute to require the Department of Education to calculate and publish grades if the next governor decides against it.

In addition, at least half of the states with letter grades incorporated them into the plans that have freed them from some requirements of the federal No Child Left Behind act. To comply with the terms of the waivers, those states must continue to apply letter grades to schools.

By contrast, the waiver that the U.S. Department of Education recently approved for Maine is based on a different school rating system, with labels such as “priority,” “focus” and “meeting.”

Maine Department of Education officials have said they will continue to use A-F because it’s clearer for the public, but there’s nothing in Maine’s waiver that requires the state to use the letter grades.

Warren said in a year or two, school leaders will come to expect and even welcome the grades.

“Schools will be calling for this, especially for schools that are making progress,” she said. “They’re going to keep wanting that annual opportunity to show off what they’re doing.”

Rachelle Tome, the state’s chief academic officer, said being in statute wouldn’t necessarily protect the A-F system because a future Legislature could always repeal it.

“Does the state want its own accountability? Do we want some level of understanding of how our schools are doing?” Tome said. “I think those are the questions.”

The first attempt to create a rating system in state law failed. Shortly after the release of the report cards, Democrats introduced L.D. 1540 to create a task force to design a school rating system that would incorporate more years of student assessment data, college enrollment rates, interviews with parents and comparisons within regional and economic peer groups.

The bill was approved by majorities in the Legislature, but not the two-thirds majorities it required as emergency legislation, or that would have been necessary to override a likely veto by LePage.

The bill’s sponsor, Sen. Rebecca Millett, D-South Portland, said she still views the A-F system as inherently flawed, but she’s not inclined to submit a similar bill in the next regular session because it would probably suffer the same fate.

“I don’t expect that people’s positions have changed,” said Millett, the Senate chairwoman of the Education and Cultural Affairs Committee. “We want to be careful how we spend our time and make sure it’s worth our effort.”

Rep. Matt Pouliot, R-Augusta, however, said he expects more legislative action on school grades, both in opposition and in support.

“I think moving forward you’re probably going to see some legislation to stop what’s there,” he said. “I think you’re going to see some legislation to make it part of statute.”

Pouliot, also a member of the education committee, said he supports A-F grading, but he wants the system to recognize the challenges faced by schools with low-income populations and to provide more support to those schools.

The letter grades, like the standardized test scores weighted heavily in the grading formula, are strongly correlated with schools’ economic profiles.

A different approach

Some school leaders aren’t necessarily opposed to A-F grading, but want it to be recalibrated with input from educators. Greg Potter, superintendent of Newport-based Regional School Unit 19, said the development of the system seemed rushed, when it should have happened deliberately and with the involvement of the Legislature.

Potter said state officials should convene a group that includes administrators, teachers and community leaders to discuss the grades.

“I just think more work could be done in getting folks together and discussing how this is impacting schools and how meaningful the data is and how effectively the schools can use the data,” he said. “It seems like that would be the next step for the state.”

Maine Education Association President Lois Kilby-Chesley said she’d want to do away with A-F grading altogether. The teachers union could potentially support grading school performance if the measures went beyond the standardized test results and graduation rates now fed into the formula, Kilby-Chesley said — measures that give a more complete picture of individual schools.

“Although the state may have dubbed some of the schools Fs, they are in fact highly functioning schools, and I think a lot of teachers were highly offended by the grading system and how it was used,” Kilby-Chesley said. “Now, of course, we can see in other states how the grading system has not worked very well.”

Kilby-Chesley was referring to the scandal surrounding Tony Bennett, who stepped down as Florida’s education commissioner on Aug. 1 after the Associated Press reported that when Bennett was Indiana’s state superintendent, he quietly changed Indiana’s A-F formula last year.

The change ensured that a charter school run by one of Bennett’s most prominent campaign donors received an A rather than a C. It also boosted grades for 165 other schools, according to an analysis by a public broadcasting outlet in Indiana.

Even before the controversy arose in Indiana, both supporters and critics of Florida’s A-F system were questioning its validity after it was adjusted at Bennett’s recommendation to blunt the impact of tougher standards on school grades.

While in Indiana, Bennett led the charge for A-F grading and other reforms similar to ones LePage has pushed, and Bennett headlined LePage’s education conference at Cony High School in March.

After Bennett’s resignation, Education Commissioner Stephen Bowen released a statement calling Bennett a “trailblazing education leader” and reaffirming his support for the types of reforms Bennett advocated.

Bowen is resigning to become director of innovation for the Council of Chief State School Officers, an association of state education commissioners. His last day is Sept. 12.

Supporters of school accountability ratings said the allegations in Indiana have raised questions about transparency, consequences attached to school ratings and possible over-simplification in A-F systems.

Carrots and sticks?

Michael Petrilli, executive vice president of the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute in Washington, said letter grades are the best ratings for schools because they’re easy to understand, but the simplicity can also be a problem.

Single letter grades usually result from complicated, behind-the-scenes formulas, Petrilli said, and can obscure strengths and weaknesses within a school. Petrilli would prefer that schools receive separate grades for things like reading and math, or for the progress of low-performing students and high-performing students.

“I think parents could probably handle a handful of letter grades for schools,” he said. “We don’t get a student report card and expect to see only one grade. We see five or six grades on there, one for each subject.”

Marc Porter Magee, president and founder of the New York-based education reform organization 50CAN, said letter grades are a good idea, but they’re still in the experimental phase and sometimes seem to emerge from a black box.

“Translating that good idea into an actual system that’s trustworthy and that is accurate has proven to be really complicated,” he said. “And that’s not to say it’s not possible, it’s just that a lot of states have struggled to make those work, and at the same time they’ve attached consequences.”

In many states, school ratings come with carrots or sticks in the form of funding, bonuses or school autonomy. In some cases, schools with multiple years of bad grades are subject to turnaround efforts that can involve increased state oversight or the mandatory replacement of staff.

None of those things are a part of Maine’s A-F system, which Magee said may be good.

Transparency is key

Anne Hyslop, an education policy analyst with the New America Foundation in Washington, also said it may be better to use school grades just for reporting information, rather than attaching consequences. But the reporting has to be clear about what’s being measured and how it’s calculated.

“Without that sort of public trust in the system as valid and fair, it undermines the whole notion of school accountability to begin with,” Hyslop said.

Magee and Petrilli also emphasized the need for transparency, and Petrilli said the controversy around Bennett’s actions has prompted healthy conversations about what to measure and how.

Some of the data in Maine’s report cards are easy to find elsewhere, like graduation rates and the percentage of students who meet proficiency on standardized tests. But the elementary and middle school report cards also assign points for growth shown by individual students, whose results are confidential.

It’s not clear yet whether what happened in Indiana will slow or reverse the momentum for A-F grading.

Jaryn Emhof, spokeswoman for the Tallahassee-based Foundation for Excellence in Education, said adoption of A-F systems may slow as states make sure their calculations are correct and are developed in a transparent way. The foundation, founded by former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, is one of the primary proponents of A-F grading.

Emhof said Bennett noticed a flaw in Indiana’s formula and did the right thing by fixing it, though maybe it would have been better to run it by the state board of education.

“I think what we’ll probably be advocating is, take your time, don’t rush, because this is really important,” she said. “If it’s not quite right and people don’t understand it, see how quickly it becomes a big story, and it creates more confusion in the long run.”

Emhof said that transparency and the potential for problems in formulas are issues for any method of rating schools, and A-F at least gets people talking about how to measure and improve school performance.

Hyslop said it would be difficult to roll back or significantly change A-F grading in most of the states that have it because of the legislation or No Child Left Behind waivers in place, but policy makers in other states might pause or rethink the design and use of school rating systems.

“My hope is that it’s not used as a rationale to get rid of school accountability full stop but to really have a conversation about what the best systems are and what systems are most fair,” Hyslop said. “I do think there are some merits to having a simple system, but you have to be careful that the system is totally transparent and that all conversations about calculations are held in a public manner.”

Magee said he expects the debate to continue along two tracks.

“I think that in states where the state leaders really believe in the system, they’re going to have to double down to make sure that they’re building something that is accurate and trustworthy and does what we want it to do,” Magee said. “That’s going to take more work, because I think a lot of questions have been raised. Some other states that were considering it might say, ‘This is more trouble than it’s worth.'”

Susan McMillan — 621-5645

smcmillan@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.