In her debut novel of psychological suspense, Christine Mangan takes her readers back to an era when questions of identity couldn’t be answered by a quick Google search, nor danger averted by a handy cell phone.

A graduate of University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast MFA program and a recipient of a Ph.D. from University College Dublin, Mangan opens “Tangerine” with a cryptic but gripping prologue, told from the point of view of an unnamed patient in what seems to be a hospital or sanitarium. The institution is in Spain, but the patient’s memory is focused on Tangier, in Morocco.

The woman says, “Most times, the city appears as a fevered dream, a sparkling mirage I can just about convince myself was real once, that I was there and that the people and places that I recall were tangible and not translucent ghosts that my mind has conjured up.” By then, the reader knows the novel is really set in the Land of the Unreliable Narrator.

The narrative’s primary action takes place in Tangier in 1956, just as Morocco is negotiating for independence from France. The chapters ping-pong between the perspectives of two women in their early 20s, Alice Shipley and Lucy Mason. Both women have a slippery relationship with the truth, April more forgetful and tentative about her memories, Lucy prone to embellishment and fabulation. Mangan quickly hints that either might eventually become the patient in the Spanish retreat.

Newly married, unaccustomed to Tangier’s oppressive heat and fearful of its crowded streets, Alice finds herself holing up in her flat while her husband, John McAllister, is off conducting business during the day, the details of which are extremely vague. Alice is shaken out of her incipient agoraphobia by the arrival of Lucy, her roommate from Bennington College in Vermont. Alice and Lucy were once the closest of friends, but something bad happened there about a year ago, an incident neither wants to speak about.

Comfortable in her skin and not at all shy about her ambitions, Lucy rapidly insinuates herself into John’s and Alice’s life and apartment, even though no explicit invitation has been extended for her to move into their spare bedroom.

Alice can’t understand why Lucy has suddenly arrived in Morocco, and Lucy can’t see why her former roommate is reluctant to pick up their friendship where they left off. “Tangerine” gradually reveals that both young women are keeping secrets, not only from each other but from themselves.

Not intimidated by Tangier’s public spaces and hidden alleys, Lucy makes the acquaintance of Joseph or “Youssef,” a somewhat sinister figure who may be a grifter and who offers visitors to the city the chance to see the sites only the locals know about. For reasons she can’t quite explain, Lucy tells him her name is Alice.

Later, he gives her advice about the dangers of Tangier: “‘If you are not smart at home,’ he said, tapping his head, ‘you will not be smart here. If you run into trouble at home, do not be surprised to run into trouble here. You are still the same person. Tangier can be magic, but even she is not a miracle worker.'”

As the real Alice frets about when Lucy plans to leave Tangier, Lucy does a thorough job of irritating John, questioning his intelligence, reminding him of his difficulty in starting a family with his wife, and pushing for information about the trust fund checks that arrive regularly from Alice’s controlling aunt in England and that seem to be all that keeps the family afloat. Lucy also notes the interest John takes in another woman at a local jazz club, and files that data away for use at a later time.

To relate more of the plot would be to rob the novel of its many pleasurable twists and turns. “Tangerine” is likely to remind mystery buffs of the work of Donna Tartt, author of “The Secret History,” and of Patricia Highsmith, author of “Strangers on a Train” and “The Talented Mr. Ripley.” Mangan’s plotting has the crackling unpredictability of Ruth Rendell, especially when Rendell wrote under her Barbara Vine pen name.

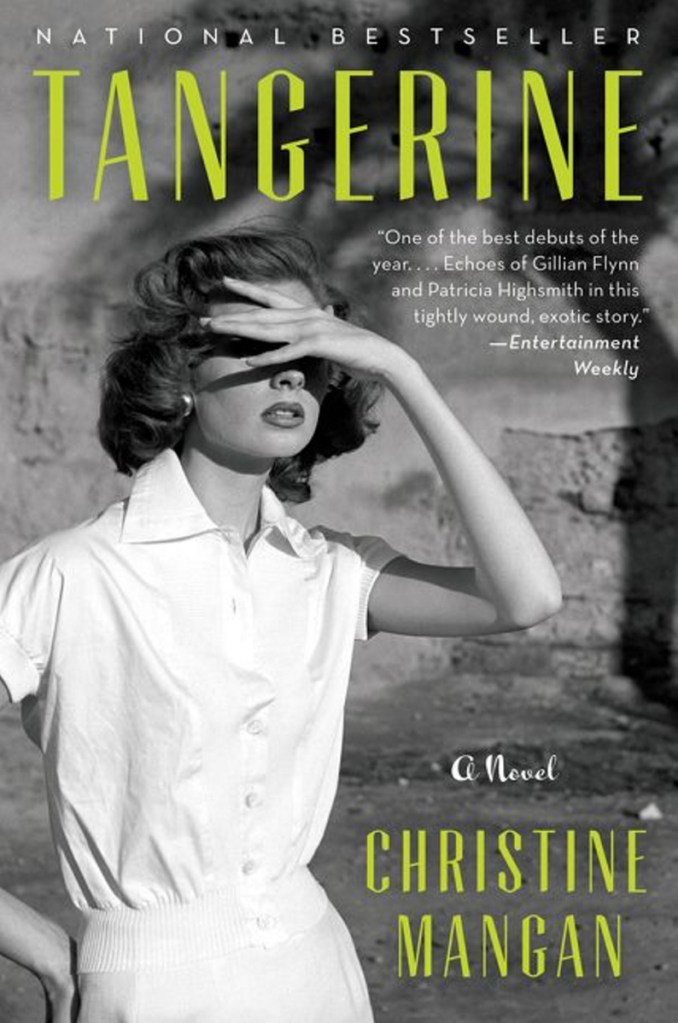

“Tangerine” is meant to be consumed at a rapid pace, so no time is left over to poke at the plausibility of its reversals. Reportedly already being adapted into a film for Scarlett Johansson, the novel has an intensely cinematic quality, conjuring scenes that might easily play upon the mind’s eye in crisp black-and-white.

Mangan plays with familiar tropes, but she deploys them with wit, insight and precision. She hides some literary Easter eggs in her prose, including tips of the hat to the Brontes, to Shirley Jackson (penning tales of paranoia back in Vermont), and to expatriate writer Paul Bowles, author of “The Sheltering Sky.”

Youssef tells Lucy that naive European visitors to the city are called “tangerines,” after the thin-skinned citrus fruit. With its tantalizing themes of obsession and the fluidity of identity, “Tangerine” is a welcome and refreshing burst of literary tartness, a deliciously juicy summer read.

Berkeley writer Michael Berry is a Portsmouth, New Hampshire, native who has contributed to Salon, the San Francisco Chronicle, New Hampshire Magazine, the Los Angeles Review of Books and many other publications. He can be contacted at:

mikeberry@mindspring.com

Twitter: mlberry

Send questions/comments to the editors.