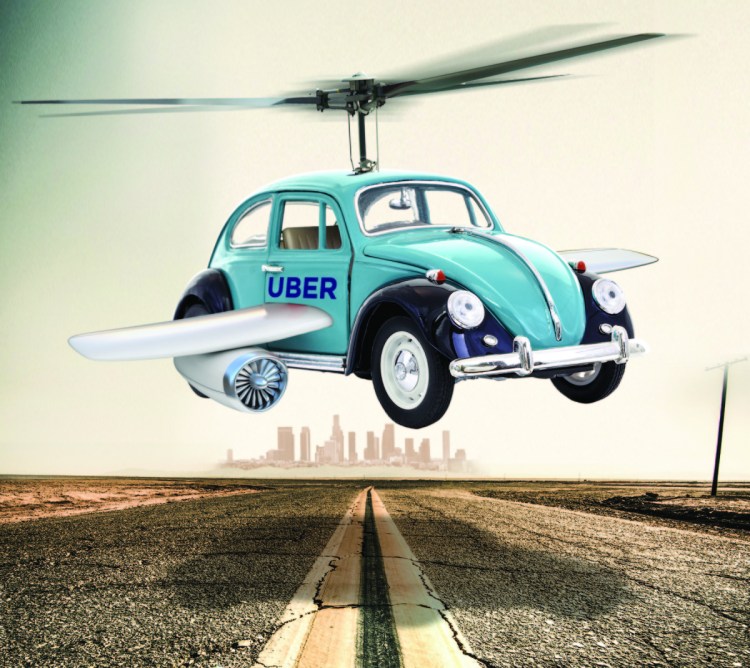

When Uber announced early this month that it was entering into partnerships – with NASA and the Army’s research wing, among other entities – to bring flying ride-share to Los Angeles by 2023, my first thought was “Blade Runner.”

The Ridley Scott science fiction film, released in 1982, takes place in 2019 and portrays a dystopian Southern California in which the urban core has crumbled into chaos and darkened skies are filled with unrelenting rain and airborne vehicles. The further we get from the 1980s, the more the film’s vision of the future seems like a reaction to its own time rather than a projection into ours. Except perhaps for those cars.

The appeal of flying ride-share is pretty clear. The drone-like vehicles on Uber’s drawing boards could mitigate the congestion on our overloaded streets and freeways, and zip us across town like VIPs.

At an early May conference in Los Angeles, Uber Elevate head Eric Allison referred to what he called “the 3-D space of the air.” What he means is multiple layers, varying altitudes, the idea that flying vehicles would not be restricted by such earthbound necessities as lanes and off-ramps.

But the skies over Los Angeles are already crowded: news and traffic helicopters, aerial tourism, police choppers, airplanes taking off and landing at LAX, Santa Monica, Burbank, Van Nuys, Long Beach, Ontario.

To its credit, Uber acknowledges these issues: “A successful, optimized on-demand urban VTOL (vertical takeoff and landing) operation … will necessitate a significantly higher frequency and airspace density of vehicles operating over metropolitan areas,” a 2016 company white paper avers.

When it comes to a solution, though, what Uber mostly has to offer is conjecture. “It may be possible,” the report continues, “for hub airport airspace to embrace ‘cutouts’ … that can dynamically open up more airspace to non-controller managed flight.”

“May be,” of course, is a long way from “will be,” or “is.”

“There are airspace questions that arise with having more than just a few rotorcraft vehicles flying around a metropolitan area,” Seth Young, director of the Center for Aviation Studies at Ohio State University, told Wired magazine last November, when Uber first publicly floated the idea of flying cars.

Even if this mix of tech entrepreneurs, NASA and the military can solve that puzzle, there is still the issue of ride sharing itself. No one doubts Los Angeles has a transportation crisis. Yet at ground level, ride sharing is almost certainly part of the problem instead of the other way around. A report produced last year at the University of California at Davis found that “services like Uber and Lyft attract passengers away from public transit, biking and walking” – by as much as 60 percent.

It is in Uber’s interest to present its model as utopian; its goal, after all, is market share.

The same is true of Elon Musk, whose ambitious Loop project received fast-track approval in April from the Los Angeles City Council’s public works committee to build a 2.7-mile tunnel under Sepulveda Boulevard. (Lawsuits against the project have been filed.) When or if it is completed, supposedly at no cost to the public, Musk’s Loop could extend from Torrance to the Getty museum, Dodger Stadium to the beach.

More science fiction? Maybe so. But less than a week after the Uber Elevate conference, Musk announced that a test tunnel in Hawthorne might open with “free rides to the public in a few months.”

In the end, should we rely on the profit-driven private sector to build our transportation future? Uber presents a troubling case.

Last year, its CEO, Travis Kalanick, and several executives resigned in the wake of allegations of pervasive gender discrimination and sexual harassment. In November, the company was fined nearly $9 million by the Colorado Public Utilities Commission for failing to put its drivers through sufficient background checks.

Around the same time, Uber admitted that a data hack had jeopardized the personal information of 57 million customers and employees.

This scandal looms as particularly disturbing when you consider Uber Elevate’s public-private relationship with NASA and the U.S. military. I’m not happy about a company that knows a lot about me – where I go, when, with whom and how I pay for the ride – sharing anything with the government.

Los Angeles is at a transit crossroads. The old model is antiquated, overloaded, and new ones have yet to fully arise. Over the next few decades in Los Angeles, we will see – at the least – the continued buildout of Metro’s light-rail and subway network, as well as the addition to our streetscapes of autonomous vehicles.

The future rarely turns out the way we imagine it will. For proof, just look at “Blade Runner.” The real city is more coherent, far less disrupted than Scott’s Los Angeles.

As for travel by corporate drone above the ground, or on a rich man’s hyperloop underneath it, that I think is dystopia by another name.

Send questions/comments to the editors.