BIDDEFORD — Both of Meredith Roberts’ “very civic-minded” parents – William and Sylvia Searle of Saco – donated their bodies for medical training at the University of New England. The Searles lived into their 90s, and it was their final act of selflessness after a lifetime of volunteering.

“My parents felt that when it was their time to pass away, they felt strongly that if their bodies could be used for the common good, that’s what should be done,” Roberts said. The couple died nine years apart, and their remains are now buried in a family plot in Salem, New Hampshire. Roberts, of Cape Elizabeth, said she believes her parents made the decision together about 20 years before her father died in 2008. Her mother died in 2017.

“They were big supporters of the community and they felt it was very important to assist in medical research,” she said. “They also had a deep faith.”

While whole-body donations are an after-life decision that few make, cadavers are a crucial tool for medical education, and UNE officials say the need and demand for whole-body donations is increasing.

The need for cadavers has gone up and there will be an even greater demand in future years, UNE officials said.

UNE HAS ROUGHLY 80 ON HAND

The university’s College of Osteopathic Medicine now has about 80 cadavers on hand for training, compared with about 40 two decades ago and about 60 five to 10 years ago. It’s the only licensed medical school in the state that operates a whole-body donation program.

“The more we have, the more we can do,” said Dr. Jane Carreiro, dean of the medical school at the Biddeford campus.

UNE is taking out a first-ever advertisement thanking people who previously donated and raising awareness about the program, for those interested in donating their body to science when they die.

Meredith Roberts of Cape Elizabeth with a photo of her parents, William and Sylvia Searle. The couple made a whole-body donation to UNE’s medical program. “They felt strongly that if their bodies could be used for the common good, that’s what should be done,” she said.

“We are the only program in the state with a whole-body donation program. We have a very generous population in this state of people who want to give back,” Carreiro said. “There is no greater donation. You are donating yourself.”

UNE has partnerships with Husson University and Northeastern University and provides continuing education for Maine doctors, dentists, optometrists and nurses. Many times the medical professionals will come to UNE to do training on cadavers, and sometimes the university will send cadavers to medical facilities to be worked on.

There don’t appear to be any official statistics on how many whole-body donations for medical training occur in the United States, but a 2016 National Geographic article estimated the number at fewer than 20,000 per year. That compares with 120 million registered organ donors, many of whom sign up to be organ donors when getting their state driver’s license.

Some medical schools in recent years have reported a surge in whole-body donations – such as the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester – while others struggle to receive enough donations for their programs’ needs.

‘BOOKWORK DOESN’T DO IT JUSTICE’

Carreiro said the demand for whole-body donations is only expected to grow, driven in part by increasing enrollments at UNE’s medical school, where class sizes have increased from 120 to 165 in the past five years.

“As professions continue to advance, they need more intense anatomy training,” she said. “Getting it from books doesn’t work.”

Whole-body donations are similar to but more involved than organ donations. Potential donors must sign forms and not be receiving hospice care, and the university can decline to accept a donation for a number of reasons, such as if the body is too badly decomposed or has infectious diseases, including hepatitis or tuberculosis. A 1960s-era state law guides the process at UNE, but a donor must be at least age 18 and a resident of Maine.

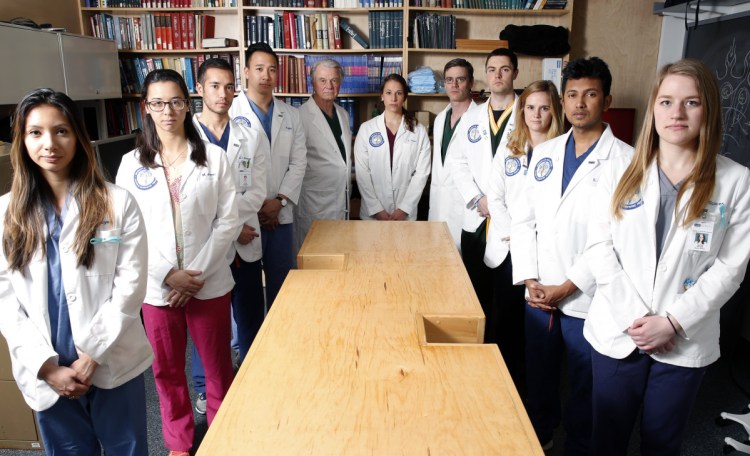

At the medical school, a cadaver is assigned to a team of four students. Sarae Sager, a Caribou native, said she and her classmates appreciate the donations and become emotionally attached to the cadavers they work with.

“It’s really important. The bookwork doesn’t do it justice,” she said. “It gives you further appreciation of how complex the human body really is, and how much we still have to learn about it.”

As required by state law, the bodies are “de-identified,” so the students know nothing about who the person was. Some teams give nicknames to the cadavers, although Sager said her group didn’t do that.

Carreiro said the cadavers are considered “part of the team.”

She said over the course of a year of study, the students can unlock some of the mysteries of what happened to the person, sometimes revealing a cause of death or other medical conditions.

“You can see if someone had arthritis or had a hip replacement or had a pacemaker,” she said.

After the bodies can no longer be used for medical training – usually in a year or two – they are cremated and the remains are either returned to families or buried in a plot at the university. UNE hosts a ceremony every September honoring the families. As the sun sets, a bugler plays taps and rose petals are placed at the site, where an undated plaque honors the donors.

“Here lies those in death who gave of themselves that others might learn and still others might live,” the plaque reads.

Carreiro said her stepmother, Ellie, decided to be a whole-body donor after visiting UNE several years before her death in 2017.

“She joked that it was the only way she would get into medical school,” Carreiro said.

SEARLES’ GIFT CAPS OFF LIFE OF GIVING

William and Sylvia Searle discussed the decision to donate with their children to ensure everyone was supportive. They chose to have a memorial service at a church after they died, even though their remains weren’t present.

For the Searles, the whole-body donations culminated a lifetime of giving to the Saco-area community. They were heavily involved in volunteering for the Foss Street Methodist Church, the Saco library, Meals on Wheels, Saco Food Pantry, Maine Home for Boys, Webber Hospital, the PTA and many other local causes.

They married in 1946, after William returned from serving in the U.S. Army Air Corps in World War II. William is now buried at the family camp in Salem, New Hampshire, near where the Searles grew up before moving to Saco in 1955, when William got a job at the Pepperell Manufacturing Co. When they lived in Saco, they would return to the family camp in New Hampshire often during the summers.

Roberts, 67, said that when her parents made the decision to donate their bodies to UNE, they talked to their children, herself and brothers William and Gregory, to make sure the family was at peace with the decision. She said they all supported the idea, and her parents only occasionally referred to the donations, usually to remind them of what needed to be done when they died. They had the signed paperwork and instructions for the funeral home for the body donation when they died.

Roberts said her parents chose to have a memorial service at a church after they died, even though their remains were not present because they had been sent to UNE. At the service, both had giant photos displayed where the casket would have been. William’s service was at United Baptist Church in Saco, and Sylvia’s was at St. Martin’s in the Field Church in Biddeford Pool. The Methodist church they went to for many years had closed by the time they died.

Roberts said that when her dad’s remains were returned to the family two years after his death, they held a private graveside ceremony in Salem at their camp. Her mother’s body is still being used by the medical school, she said.

She said the graveside ceremony was much happier than in the immediate aftermath of William’s death at age 92, when the family was mourning his passing and somewhat shocked despite his age.

Sylvia, who died at age 93 in September, will be buried next to him when her remains are returned.

“It was joyous, because time had elapsed, and we were all happy knowing that his wishes were granted,” Roberts said. “We said, ‘Here you are, Dad. We’re all with you at camp now.’ ”

Joe Lawlor can be contacted at 791-6376 or at:

jlawlor@pressherald.com

Twitter: joelawlorph

Send questions/comments to the editors.