Frank Brockman Gallery in Brunswick has been around for a while, but it’s kept a low profile. More recently, however, the gallery has sparked with energy under the curatorial directorship of painter Mark Little. The third floor space is one of the more handsome galleries in Maine, and it finds its mark with an exhibition of paintings and drawings by Tom Flanagan, whose studio is only yards away in Fort Andross – one of the leading studio centers in Maine.

Flanagan’s paintings are dynamic and complex hard-edge abstractions. I have followed his work for years, and the newest pieces have attained a scale and ambition that is rare for abstraction in the region, despite the ascendancy of abstraction in Maine.

Flanagan’s paintings go deep into modernist logic. They are bold with color and contrast. The forms are dynamic to the point they seem to be ever-swirling with clockwork logic. Yet, instead of the emotional writhings of Baroque or Romantic art – an effect championed not only by Bernini, Tieoplo and El Greco, but by the great American painters of Abstract Expressionism such as Pollock and de Kooning – Flanagan’s works breathe with a sense of living logic, of poetry that looks not to play on our emotions, but to let our eyes lead us around something like a gameboard of formal (design) intelligence.

“Just Close Your Eyes,” for example, is a 4-foot-square canvas. Surrounded by a white margin, the painted forms quietly become a figure on the white page-like ground. The complex set of trapezoids and geometrical forms coalesces to give an easy appearance of something like a boldly colored quilt made of folded colored paper. And while the general feel is lively, approachable and unified, it leads the viewer’s eye to its details. These create different types of systems within the large – and quite effective – compositional structure. A form in the lower right corner is 3-D. A black lattice in the lower middle expands space by both its openness and its apparent print technique. This drags our eye to nearby print-system passages, such as the gray Ben-Day dotted cube edge just above it.

Flanagan’s shift from surface to interior logic is like architecture. Imagine the Portland Museum of Art, designed by the great Henry Cobb. The facade presents itself immediately as the face of the PMA, but it’s the inner workings that ultimately matter most to us: function, flow, form, egress and so on.

Not to imply any literal intent on Flanagan’s part, but “Just Close Your Eyes” and his other works act like museums of Modernist chops. To be clear, this is precisely how I understand the late Cubism of Picasso and Braque – and Flanagan’s work certainly looks and acts like late Cubism – but the wit and play of Cubism unfurls itself more like an encyclopedia than museum architecture. It is jumpy, pointy, sly and deceitfully clever. Flanagan’s paintings are more attuned to putting his painterly process on the same page as our viewing process. His choices, his decisions, his intentions are saddled in plain view, and we get the sense that his ultimate standard is not radical or conceptual but cultural. In the end, his sensibility-soaked choices are made in the spirit of creating a good painting. The work has to satisfy him. And he wants us to come to the same conclusion.

As far as I am concerned, Flanagan is absolutely successful.

“Wave After Wave” is one of Flanagan’s more visually complex canvases. It, too, uses a white margin that also underlies much of the painting, which opens it up spatially but also makes the work feel more like a drawing. The work begins with a picture-frame-like rectangle in the upper left corner. These forms morph and break down throughout the work (yes, “deconstruction,” but I advise against trying to apply Derrida too literally), and from them we get other painterly systems. There are wispy witticisms of form, such as a protractor-like shape and a diagrammed cone form (perhaps a Cezanne reference). There is a black form with a brick-like grid on it. And pushing in from the right is a large geometrical section that feels like a playful introduction to single-point perspective. If you want to, you can see this work as a history of painting. But Flanagan is neither didactic nor so literally metaphorical. I see this piece connecting to the rest of his work more in terms of systems play and visual satisfaction.

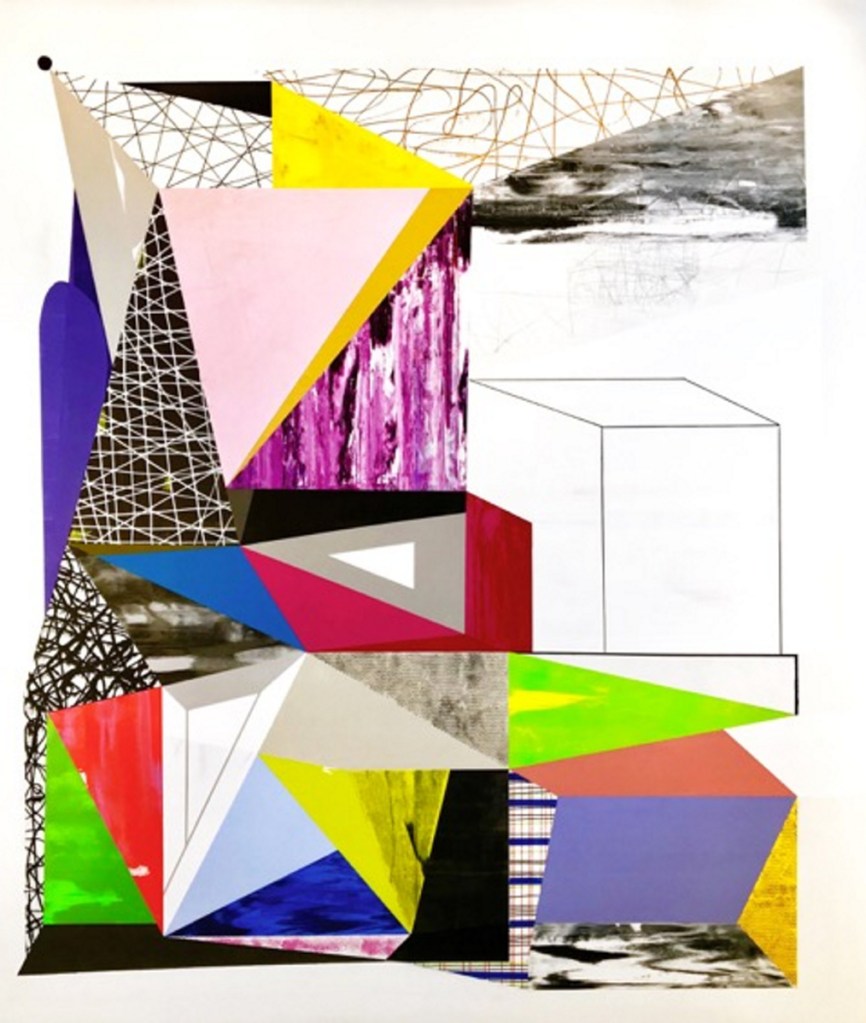

“Hopscotch” is an 8-foot abstraction of almost unsettling ambition. Much of the surface remains white, so the “figure” rises up architecturally from the left. While the title “Hopscotch” will likely lead viewers to see the drawing on the right (a simple, unpainted cube) and at the top in terms of game logic (linear, in time, and with a specific desired outcome), I think it has more to do with the way Flanagan seems to have literally built this form from the ground up. The dense masses rise above each other, finally reaching out with longer triangular gestures toward the top. It’s a painting about painting, formal play and process. This is not to say that such works are insular or hermetic, dedicating themselves only to a select audience – quite the opposite. This is the basic truth of abstraction: It’s not pretending to be something it’s not. It’s a painting. We don’t go to museums to see, say, presidents, naked ladies and fruit in bowls. Rather, we go to see paintings: portraits, nudes and still lifes. I think abstraction happened around the world a century ago because Cubism inspired many artists to realize that painting is about recognition, and it is enough that we recognize that something is a painting. It’s not art because it pretends to be something else. It’s art because of what it does out in the open.

Flanagan’s elegantly intelligent canvases are joined by a suite of handsomely framed pastels. These seem to be what Flanagan does to help the visual ideas flow with such robust urgency. (It’s one thing to let it fly with a loose brush, but his paintings are made more with trowels and tape than brushes.) Their dense excitement is palpable. They are freer and more energetic than the larger works, but in their quickness, they can’t achieve the well-considered dynamics of the paintings. They complement each other and help us see Flanagan’s process: action, decision, system, adjustment, inclusion, reversal and so on.

“Show Me the Garden” is a show of great paintings in a space that suits them rather perfectly.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.