LAC-MEGANTIC, Quebec – Canadian authorities said they have opened a criminal investigation into the fiery wreck of a runaway oil train in this small town as the death toll climbed to 15, with dozens more bodies feared buried in the burned-out ruins.

Quebec police Inspector Michel Forget said Tuesday that investigators have “discovered elements” that have led to a criminal probe. He gave no details but ruled out terrorism and said police are more likely exploring the possibility of criminal negligence. Provincial police spokesman Sergeant Benoit Richard said no arrests have been made.

The death toll rose with the discovery of two more bodies Tuesday. About three dozen more people were missing. The bodies that have been recovered were burned so badly they have yet to be identified.

Investigators zeroed in on whether a fire on the train a few hours before the disaster set off a deadly chain of events that has raised questions about the safety of transporting oil in North America by rail instead of pipeline.

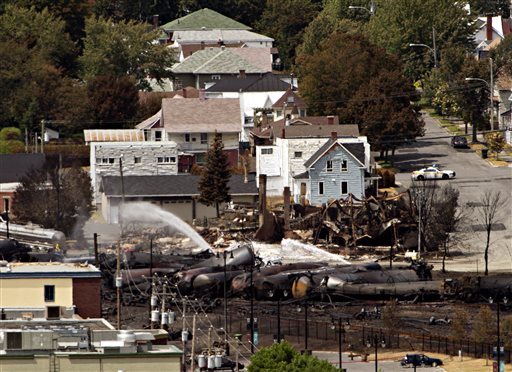

The unmanned Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway train broke loose early Saturday and sped downhill in the darkness nearly seven miles (11 kilometers) before jumping the tracks at 63 mph (101 kph) near the Maine border. All but one of the 73 cars were carrying oil. At least five exploded.

Rail dispatchers had no chance to warn anyone during the train’s 18-minute journey because they didn’t know it was happening themselves, Transportation Safety Board officials said Tuesday. Such warning systems are not in place on secondary rail lines, said TSB manager Ed Belkaloul.

The derailment and explosions destroyed about 30 buildings, including the Musi-Cafe, a popular bar that was filled at the time, and forced about a third of the town’s 6,000 residents from their homes.

Resident Gilles Fluet saw the approaching train.

“It was moving at a hellish speed,” he said. “No lights, no signals, nothing at all. There was no warning. It was a black blob that came out of nowhere.”

He had just said goodbye to friends at the Musi-Cafe and left. “A half-minute later and I wouldn’t be talking to you right now,” he said.

“There are those who ran fast and those who made the right decision. Those who fooled around trying to start their cars to leave the area, there are probably some who burned in them,” Fluet said. “And some who weren’t fast enough to escape the river of fire that ran down to the lake, they were roasted.”

The same train caught fire hours earlier in a nearby town, and the engine was shut down — standard operating procedure dictated by the train’s owners, Nantes Fire Chief Patrick Lambert said.

Edward Burkhardt, president and CEO of the railway’s U.S.-based parent company, Rail World Inc., suggested that shutting off the locomotive to put out the fire might have disabled the brakes.

“An hour or so after the locomotive was shut down, the train rolled away,” he told the Canadian Broadcasting Corp.

Lambert defended the fire department. “The people from MMA told us, ‘That’s great — the train is secure, there’s no more fire, there’s nothing anymore, there’s no more danger,'” Lambert said. “We were given our leave, and we left.”

Burkhardt was expected to visit the town on Wednesday. The train’s engineer, Tom Harding, has not commented publicly on the incident.

Transport Canada, the government’s transportation agency, said Tuesday there are no rules against leaving an unlocked, unmanned, running locomotive and its flammable cargo on a main rail line uphill from a populated area. Officials also said there is no limit on how many oil-filled, single-hull tank cars a train can pull.

Transportation Safety Board investigator Donald Ross said the locomotive’s black box has been recovered but cautioned that the investigation was still in its early stages.

The tanker cars involved in the crash were the DOT-111 type — a staple of the American freight rail fleet whose flaws have been noted as far back as a 1991 safety study. Experts say its steel shell is so thin that it is prone to puncture in an accident.

The derailment also raised questions about the safety of Canada’s growing practice of transporting oil by train, and is sure to support the case for a proposed oil pipeline running from Canada across the U.S. — a project that Canadian officials badly want.

Efforts continued Tuesday to stop waves of crude oil spilled in the disaster from reaching the St. Lawrence River, the backbone of the province’s water supply. Environment Minister Yves-Francois Blanchet said the chances were “very slim.”

Lac-Megantic’s mayor said about 1,200 residents were being allowed to return to their homes.

A sense of mourning had set in among the survivors.

“Everybody that is gone — we’re a close-knit community — they are my friends’ children, they’re former workmates, they’re elderly people that I know, I knew them all,” Fluet said. “I’m on adrenaline and not doing too badly, but I know that when the names come out and the funerals take place it will be another shock.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.