CALAIS — Celia Geel’s second child is due in October, and she will be making the 95-mile trek from her Calais home to Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor for the delivery.

Geel, 30, hopes she makes it to the hospital in time. Geel and other women in Calais of childbearing age no longer have easy access to obstetrics services. Calais Regional Hospital delivered its last baby in late August – aside from an emergency room delivery – and has closed down its maternity wing.

Her worst-case scenario would be giving birth at 3 a.m. on the side of Route 9 – the “airline” on the way to Bangor – a pitch-black, remote stretch of two-lane highway where cellphone service is spotty at best.

“It’s such an unknown. Will I be waking up in the middle of the night for a two-hour drive?” Geel said. “I try not to dwell on it. I have zero control over it now.”

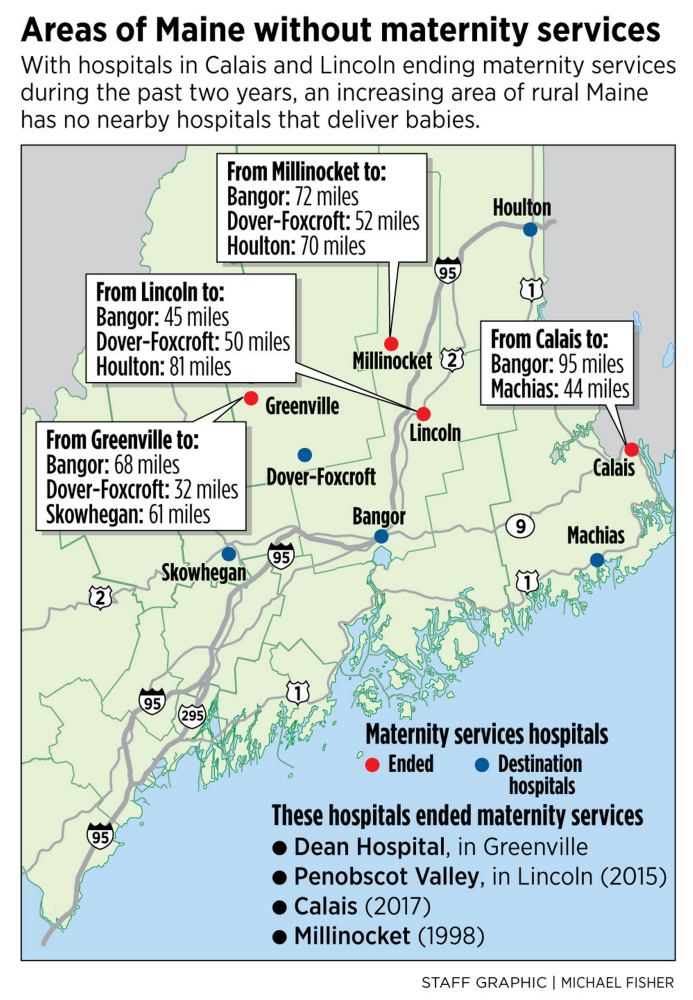

Calais, which closed its obstetrics services in late August, is the latest hospital in Maine to end its maternity services, citing financial pressure. Penobscot Valley Hospital in Lincoln ended those services in 2015 and Millinocket Regional Hospital and Charles A. Dean Hospital in Greenville stopped delivering babies even earlier, in the 1990s.

That has led to pregnant women in some areas of remote Maine – where there are hundreds of births every year – driving an hour or longer to the nearest hospital with maternity services, putting the health of women and infants at risk. The danger grows even more in the winter, when travel times can easily double and be treacherous. The loss of services also makes it even more difficult for rural areas to attract experienced doctors and nurses to live and work there.

MAINE REFLECTS NATIONAL TREND

The trend in Maine is mirrored nationally, where research has shown that about 9 percent of rural counties in the United States have lost maternity services over the past decade and about 54 percent of rural counties have no hospitals with obstetric services at all, according to Health Affairs, a scholarly magazine.

Geel is worried about several possible scenarios stemming from being so far away from a hospital, even though she tries not to fret. For instance, what if she believes she’s in labor, but it’s a false alarm?

“What are they going to do, send me back down Route 9?” Geel said. She also has to travel weekly to Bangor for prenatal appointments during the last several weeks of her pregnancy.

Had Geel’s due date been in July or early August, her baby would have been one of the last deliveries in Calais.

Cora Geel, 2, smiles as Dr. Hatem Hatem talks to her at her mother Celia Geel’s last appointment at the Women’s Health center at Calais Regional Hospital.

In Calais, the hospital is a few blocks away from the city’s narrow downtown that overlooks St. Stephen, New Brunswick. The one-stoplight downtown showcases a three-screen movie theater, thrift store, a shoe store and the Wabanaki Cultural Center, where there’s a display about puffins.

But while Calais boasts many stunning natural views, it lacks people and jobs in this 3,000-population city near the Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge.

Geel said it’s galling to think that just a few months ago, she would have had to drive less than a mile to give birth in the hospital. Now she has to travel two hours. She said she could have gone to Down East Community Hospital in Machias, about a 50-minute drive, but if there were any complications with the delivery, they would be sent to Bangor anyway, so they decided to just have the baby in Bangor.

STAFF SHORTAGE COMPOUNDS WOES

The same holds true for towns like Greenville, Millinocket and Lincoln. Rural Maine faces a combination of factors that have proved challenging for its hospitals: an aging population, young people leaving, people bypassing the local hospital for elective surgery and difficulties attracting experienced physicians and nurses.

Marie Vienneau, CEO of Mayo Regional Hospital in Dover-Foxcroft, said she headed the Millinocket hospital when it closed its obstetrics unit for financial reasons in 1998. She said “cost pressures” are a driver for rural hospitals in deciding what services to terminate or offer.

Rural hospitals are more reliant on government reimbursements from Medicaid and Medicare, which pay hospitals less than private insurers for the same services. A national study showed that 63 percent of rural hospitals’ patients were Medicare or Medicaid on average, compared with 49 percent for urban hospitals.

A delivery room sits empty in August at Calais Regional Hospital, the latest in Maine to end obstetrics services.

Rural hospitals also see more uninsured people, and the hospitals end up absorbing the costs for those unable to pay.

“It’s a horrible, gut-wrenching decision. Every hospital wants to provide these services to their communities, so when you have to give that up, it’s very difficult,” Vienneau said.

Dee Dee Travis, a vice president at Calais Regional Hospital, said the decision was “very painful” but the hospital had to close its obstetrics unit because of ongoing financial problems the hospital had been facing for several years.

The Calais hospital has seen more than $12.8 million in operating losses since 2010, and hospital officials said the hospital itself, which employs about 250, is in danger of closing altogether. The hospital’s annual revenues are about $30 million and it has lost an average of $1.8 million per year over the past seven years. Closing obstetrics will save the hospital about $500,000 per year, officials said

“We’re still in a lot of danger,” said Rod Boula, Calais Regional Hospital’s CEO. The administrative offices keep a running tally of rural hospitals – 81 nationally – that have closed since 2010. “We don’t want to be one of those numbers,” he said.

Boula said if the hospital doesn’t turn around its financial situation, Calais Regional Hospital could close within two years. Other medical services that Boula declined to disclose also could be closed or scaled back in the coming years as the hospital attempts to stay open.

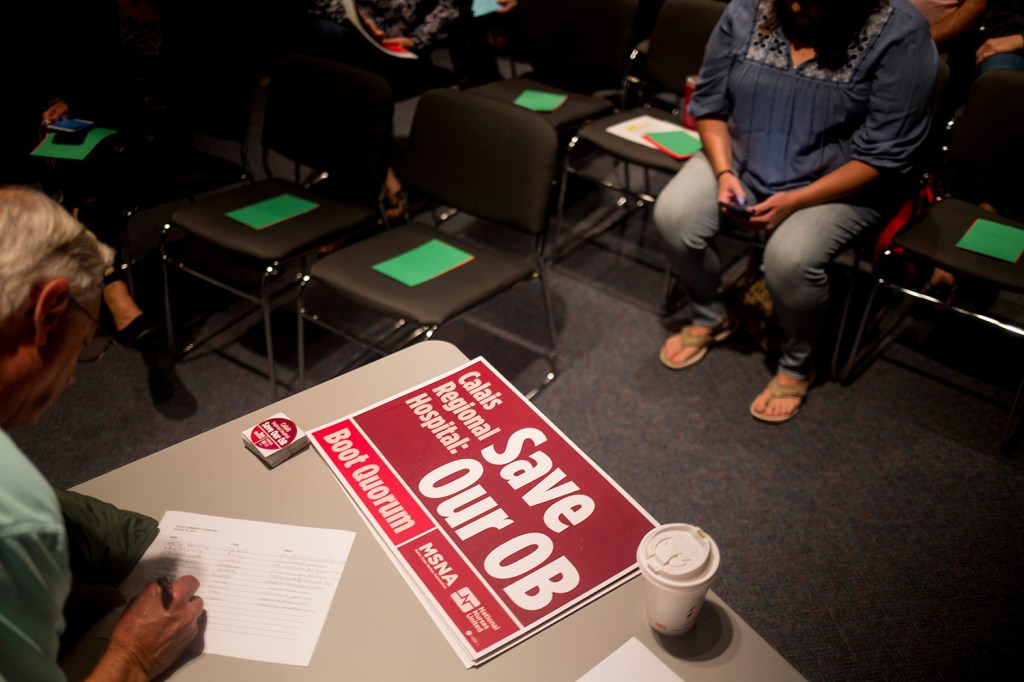

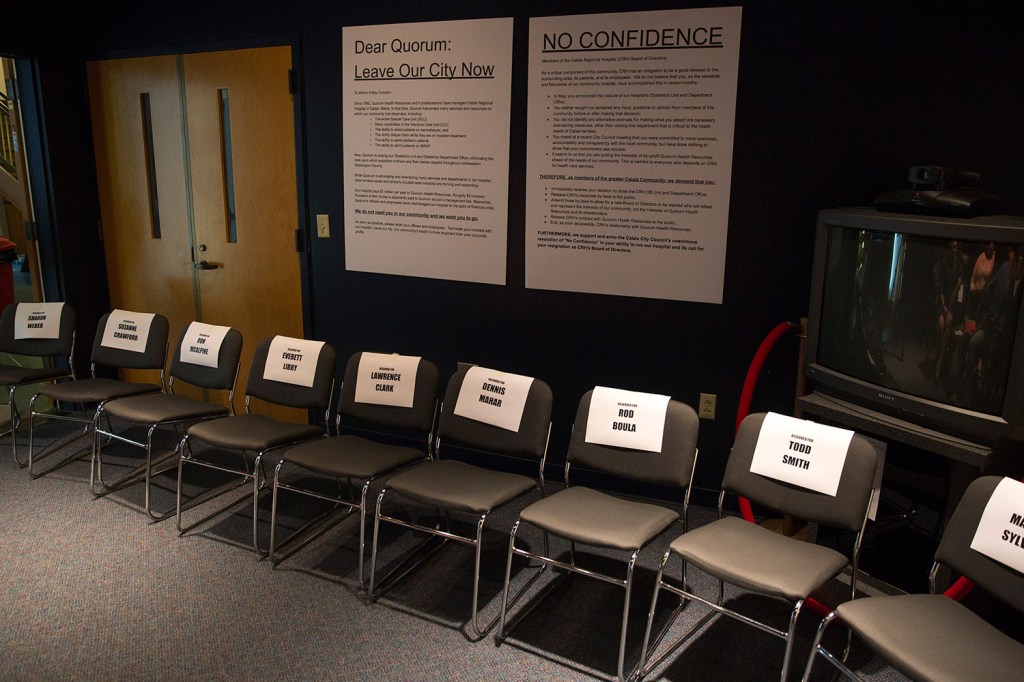

The hospital is working with Eastern Maine Medical Center and Down East Community Hospital to have obstetricians accept prenatal appointments in Calais to ease the traveling time for expecting moms. Still, the hospital’s decision to close its obstetrics unit has touched off a community controversy, including candlelight vigils, protests from the nurses’ union and a prickly relationship between hospital officials and the City Council.

Calais Councilor Mike Sherrard said that while city councilors were upset with the hospital for not informing them or the community that the hospital had been contemplating closing the maternity ward, he acknowledged that the city overall is having a difficult time. The number of paper mill jobs, once a staple in the area, is a fraction of what they once were. He described Calais as a quiet bedroom community where Canadians stop to shop at the Wal-Mart.

“We’re struggling to get by,” Sherrard said.

A woman holds a letter that the Coalition for Healthy Washington County sent to the Calais Regional Hospital’s Board of Directors asking them to get rid of Quorum, the consulting and management firm that CRH pays to run the hospital.

OBSTETRICS UNITS INSPIRE LOYALTY

Dr. Michael Pinette, a MaineHealth obstetrician who travels the state, has visited all of the obstetrics units, saying that the financial problems for obstetrics services at rural hospitals are acute, and he sees no change in the future.

“Many of these hospitals are just barely hanging onto their OB services,” Pinette said.

Andrew Coburn, a public health professor at the University of Southern Maine, said that while there are many underlying financial reasons why obstetrics is on the chopping block at many rural hospitals, it’s considered a crucial medical service and hospitals want to hold onto it if they can.

“It’s a huge reputational problem,” Coburn said of a hospital that ends maternity services. “Historically, obstetrics is the gateway for younger people into the hospital.”

Coburn said when hospitals lose traditional service lines like obstetrics, people will drive farther for elective surgery because they start losing confidence in the abilities of the local hospital. Or they simply stop thinking about the local hospital as an option for their medical needs.

“You don’t want to be known as the hospital with lots of financial problems,” Coburn said.

In contrast, Coburn said families often become loyal to the hospital where their baby was delivered, and will choose the same hospital for other health care services.

Coburn said that’s why hospitals, despite obstetrics being a money loser, invest heavily in maternity wings if they can. The money they lose in obstetrics can be made up in other surgeries, but only if people go to that hospital for the services that make money for the hospital or its system, such as orthopedics.

Katy Kozhimannil, associate professor of health policy at the University of Minnesota and a leading national researcher on the disappearance of maternal care in rural America, said hospitals consider obstetrics a “loss leader,” in a manner similar to a store pricing a popular item low and losing money on it in order to draw customers into the store, where they will also buy other, pricier items.

Kozhimannil said the reimbursement system does not favor obstetrics.

“In health care, we tend to pay more for things that are high-tech, or technology-intensive. We also tend to pay more for things people don’t want to do, or for things that are new and cutting-edge,” Kozhimannil said. “Birth is none of these. It’s as old as time, and it is a service that clinicians in hospitals genuinely want to provide. It brings joy to families and communities, and in most cases, it is very low-tech.”

Kozhimannil said the low number of babies born in a rural hospital can accelerate its financial problems, as a hospital’s expenses are about the same even when births plunge.

“You’re paying for a very expensive service for people to be on standby,” Kozhimannil said.

Volume was one of the major reasons why Calais closed its obstetrics unit, with births declining from more than 100 several years ago to 64 last year.

Kozhimannil said that when births number fewer than two per week at a hospital, staff members also don’t get as much practice delivering the babies.

The birth rate in Maine has remained steady over the past decade, hovering at about 54 births per 1,000 women ages 15-44, according to U.S. Census statistics, but it’s far below the national average of between 63 and 66 births per 1,000 women. The birth rate in rural Maine also tends to be lower than in the more populated areas of the state.

LOSSES IMPERIL INFANTS’ HEALTH

Kozhimannil said more studies need to be done on the impacts on a community when the local hospital loses obstetric services. But she said what researchers have discovered so far is not promising for the health of the babies.

“Loss of hospital-based obstetric services in rural communities usually prolongs travel time, and increased travel time may result in decreased prenatal care utilization, worse maternal outcomes, and adverse infant outcomes such as, admission to (intensive care), preterm birth, or even infant mortality,” Kozhimannil said.

Kozhimannil said the long drive to the hospital to deliver a baby may be memorable, but it’s far from ideal.

“The story of the mom delivering the baby in the parking lot because they can’t make it to the hospital, these stories become part of family lore, unless something really bad happens,” Kozhimannil said.

Caroline Coleman of Calais said she and her husband moved from Portland to Calais several years ago and, knowing they wanted to have more children, checked out the local hospitals. They were happy with Calais Regional Hospital, and Coleman has given birth to two of their three children in Calais, including a boy born six months ago.

“That literally went into our decision-making on where to live,” Coleman said.

Sherrard said losing hospital maternity services is just yet another disincentive for young people to move to or remain in the region.

“When people decide where they want to live, they look and see if you have good schools, good jobs and good health care,” Sherrard said.

Gordon Smith, executive vice president of the Maine Medical Association, which represents physicians before the Legislature, said the lack of services in rural Maine will likely lead to more home births. The number of home births in Maine has increased since 2000, but only slightly, from about 150 births per year in the early 2000s to about 200 to 250 per year in recent years.

Smith said home births are more risky than in a hospital, which can handle most complications that arise from delivery. And if the hospital can’t resolve a serious problem, it can quickly transport the infant to a hospital that can.

Hospital officials in Calais and other rural parts of Maine point to the shrinking workforce as another issue. Just as other employers in rural Maine can have difficulty attracting workers, the same applies to rural hospitals. If they can’t recruit physicians and nurses, paying for traveling doctors is cost-prohibitive.

Vienneau said traveling doctors and nurses cost three times as much as a staff position. So while Mayo is “committed” to maintaining obstetrics, Vienneau said it’s always evaluating the program’s finances.

“It’s very precarious,” Vienneau said. “There’s no magic number, but if we lose volume or staffing, it could force our hand.”

Joe Lawlor can be contacted at 791-6376 or at:

jlawlor@pressherald.com

Twitter: joelawlorph

Send questions/comments to the editors.