PORTLAND – It’s unlikely that Stephen Lanzalotta’s recipes are protected by copyright laws, experts say, but the instructions for his luna bread and Sicilian Slab pizza may include trade secrets that will make it difficult for Micucci Grocery, which fired him last week, to keep using them.

Attorneys who specialize in copyright and intellectual-property issues said they have not reviewed Lanzalotta’s recipes or interviewed anyone involved in the case, so they can only speculate how the law would apply. But they can say one thing for certain: This is a confusing case with a “strange fact pattern” that leaves lots of room for interpretation.

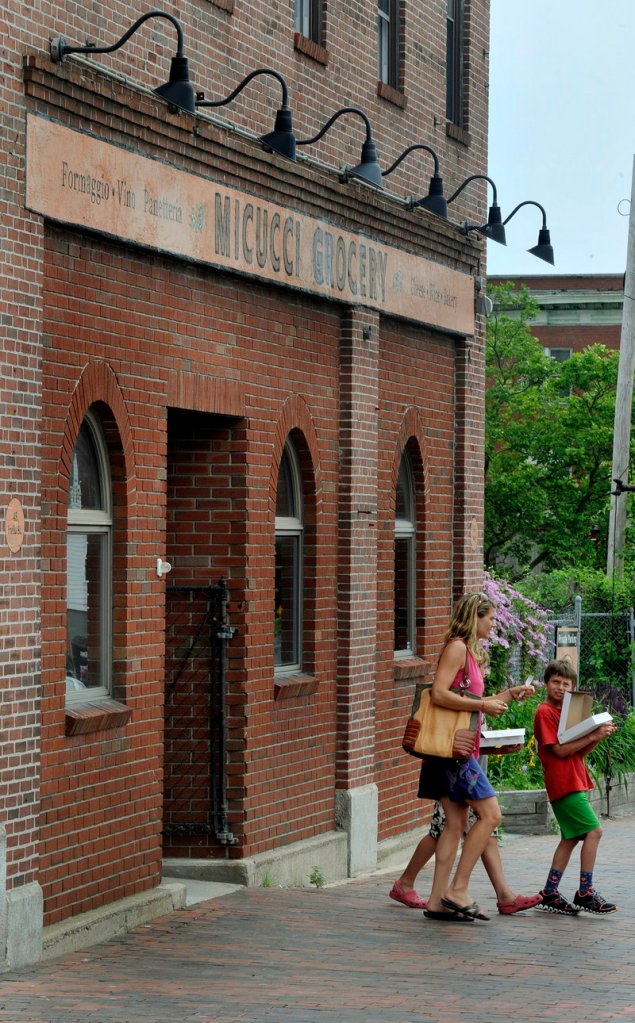

Lanzalotta’s firing from the popular Italian grocery on India Street raised some tasty legal questions: Can Micucci keep serving Lanzalotta’s creations, or does he hold the rights to his recipes? Was an oral agreement that the recipes are his adequate, or should everything have been put in writing?

Recipes fall into a gray area of copyright law, in which some parts may be protected but others are not. If recipes are created for an employer, things get even trickier. There’s also the question of whether the recipes contain elements that could be considered trade secrets.

“You’d like for it to be a nice, simple answer,” said Charles P. Bacall, a partner in the Portland law firm Verrill Dana who specializes in copyright law and intellectual property rights, “but then all lawyers would be out of business.”

The basic ingredients of recipe copyright law can be found in the U.S. Copyright Office in Washington, D.C., which says recipes that are “mere listings of ingredients” are not protected. That includes, apparently, the methods outlined for carrying out that recipe.

Copyright protection may be extended to recipes or collections of recipes (think cookbooks) that include “substantial literary expression” in the form of a description or explanation.

“What copyright really covers is creative expression,” Bacall said. “So a novel, obviously, is covered by copyright law — a statue, painting, a song, things like that. But the flip side of it is, it doesn’t protect the ideas that are expressed in that novel or song.”

That’s why recipes are so tricky, Bacall said. Take, for example, a recipe for cooking a steak on a grill. The idea of seasoning a steak with salt and pepper and throwing it on the grill and cooking it for five minutes on each side is not protected.

“But if you were to write it up in flowery language and talk about how it brings back memories of your father on warm summer evenings tossing the baseball around or whatever, all that stuff would be protectable,” Bacall said. That’s because such language would be considered “original expression.”

What if you wrote that little essay while working for someone else?

A second important component of copyright law is the “work for hire doctrine,” which says works created by employees within the scope of their employment automatically belong to the employer — absent some written agreement to the contrary.

So, for example, if you’re hired to write poetry for a greeting card company, any poem you write will belong to the company.

Lanzalotta’s case is complicated. He created his luna bread at the bakery he once owned, Sophia’s. When he was hired by Micucci, he took the luna dough and added sauce and cheese, which means he created the Sicilian Slab, as his pizza is known, under Micucci’s roof.

“I coined the name of Slab,” Lanzalotta said, “brought the dough recipe from Sophia’s, and presently hold the federal service trademark for ‘Sicilian Slab.’“

The fact that the luna bread came from Sophia’s “obviously doesn’t work in the favor of (Micucci),” Bacall said.

“In that case, a transfer of copyright has to be in writing,” he said.

For items developed while Lanzalotta worked at Micucci, “it’s not so clear.”

Keep in mind that all of this depends on whether anything in Lanzalotta’s recipes can be copyrighted. If copyright law doesn’t apply in his case, trade secret law may, attorneys said.

“It would require a lot of extra expression to justify copyright in a recipe,” said Ashlyn Lembree, a professor at the University of New Hampshire School of Law and director of the Intellectual Property and Transaction Law Clinic at the Franklin Pierce Center for Intellectual Property.

“I don’t know what (Lanzalotta’s) recipe looks like,” she said. “But it’s possible that the guts of what he really cares about are the facts and the process, which are not copyrightable, which brings us to trade secrets.”

A trade secret is a process, formula, method or technique that has commercial value and is secret. The formula for Coca-Cola, for example, is a trade secret, and people have been arrested for trying to steal it.

People can do many things to protect trade secrets, Lembree said, including “only letting employees who have a need to know, know, or maybe know only part of the recipe. Or having passwords on your computers. Or having lock-and-key on your recipe box. Or having nondisclosure agreements with your employees.”

The fact that the recipes Lanzalotta used to train employees were all marked “confidential recipe,” in red no less, “adds such an interesting twist to this scenario,” Lembree said.

It raises the question of whether the baker can sue his former employer for misappropriation of trade secrets, she said. Did the bakery have a duty to maintain secrecy or limit the use of the marked recipes? Or is Micucci’s possession of the recipes enough to allow their continued use?

“If I was a mediator in this case and I were to recommend a settlement,” Lembree said, “I’d say, ‘You guys should both use it and you guys should both come up with a trade secret policy so it’s kept as a trade secret.’ You need to put limits on what it can be used for and what it can’t.”

In the days since Lanzalotta’s departure from Micucci, both sides have had their supporters.

The store’s owners are out of town until Wednesday, and an employee who answered the phone at the grocery had no comment.

Lanzalotta says he has been inundated with job offers that range “from being a consultant to a startup boutique bakery to manufacturing.”

Paul Martino, a personal manager for actors who splits his time between South Freeport and New York, is one of the people who has offered to help Lanzalotta open his own bakery. He’s offering a newly renovated, 1,900-square-foot commercial space in South Freeport, with seating for 30, at a highly reduced rate — or even no rent at all.

Why?

“I’m Italian,” Martino said. “I want to tell you, I’ve never had pizza like that in my life, and I live in New York City. It’s on a whole other level. I’ve got Italian grandparents on both sides, and neither one of my grandmothers made pizza like this, ever.”

Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Send questions/comments to the editors.