WATERVILLE — While working for The Walt Disney Co. in the late 1930s, Damariscotta native Maurice “Jake” Day recommended that the company send people to the forests of Maine to gather inspiration for the animated film “Bambi.”

Walt Disney sent Day back to his home state for six to nine months to take photos and paint landscapes of the region around Mount Katahdin and Baxter State Park as well as animals, plants and the seasons.

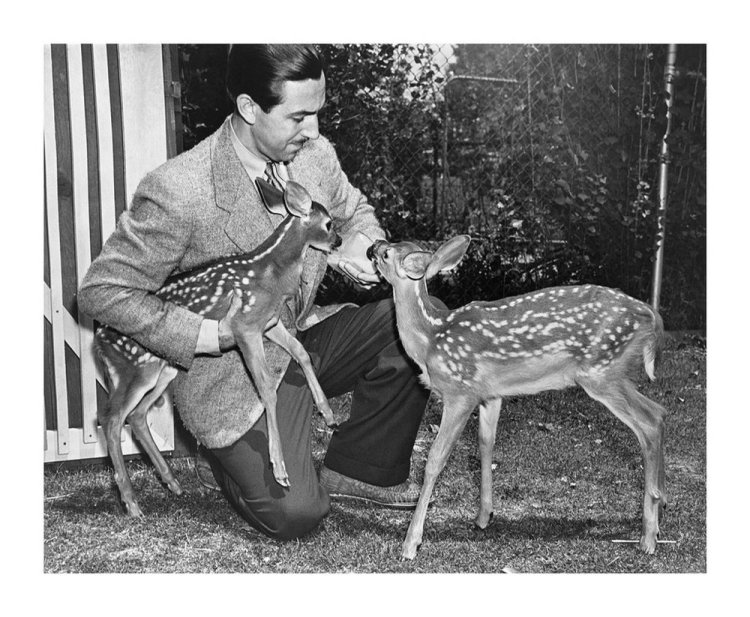

Partly because of Day’s influence, two white-tailed deer — orphaned fawns named Bambi and Filene — were sent by the Maine Development Commission to Hollywood by train for Disney animators to study, according to animator and animation historian John Canemaker. The deer lived at the Disney studio during the several years of the film’s production and were later released as adults to a zoo and then to Griffith Park in Los Angeles.

Tyrus Wong sits next to an illustration in a photograph shown during a slide presentation of Wong’s art. Animation historian John Canemaker talked on Tuesday about Wong’s involvement with the Disney movie “Bambi” during a Maine International Film Festival event at the Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville.

The music composer for the film, Academy Award-winning Frank Churchill, was also a transplant from Maine, hailing from Rumford. He was nominated for two Oscars for “Bambi,” for the score and for the song “Love Is a Song.”

Those Maine-related links are among the reasons “Bambi,” marking its 75th anniversary, was chosen as the centerpiece film for the Maine International Film Festival. A 35-millimeter version of the film, shot in three-strip Technicolor print, will be screened at 6:30 p.m. Wednesday at the Waterville Opera House. A conversation with Canemaker will follow the screening.

While the original 1923 book, “Bambi, a Life in the Woods,” was written by an Austrian man and most likely set in the woods of Europe, evidence of events such as Day’s trip and the Maine deer point to the Pine Tree State as the setting for the movie adaption.

But it wasn’t Maine that ultimately had the biggest effect on the look and feel of the film.

Canemaker, who directs the animation program at the Tisch School of Arts at New York University, gave a presentation Tuesday at the Colby College Museum of Art on Tyrus Wong, an acclaimed Chinese-American artist and film production illustrator who got his first big break as the key art director for “Bambi.”

Wong was born in southern China in 1910 and emigrated to the United States with his father at age 9. He endured poverty and racism during the time of the Chinese Exclusion Act, an 1882 federal law prohibiting the immigration of Chinese laborers that was repealed in 1943. Nevertheless, his father encouraged him to follow his passion, and he attended the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles even though they struggled to pay the tuition.

Canemaker first met Wong in 1994 while he was writing a book on animation. He described Wong as positive and cheerful, and his father had looked out for him, forbidding him to play baseball, saying, “Suppose you break one finger? You’ll ruin your whole life.”

Wong told Canemaker he couldn’t afford ink, so he practiced Chinese calligraphy with water on a newspaper. He was inspired by Western artists such as Michaelangelo but looked to the Chinese Song dynasty, which ruled from 960 until 1279, and its art that is known for its simplicity of detail.

“Seven centuries later, Wong may be considered an heir to these Song artists,” Canemaker said, adding that his new style of painting “bridged the Chinese past and Wong’s American life.”

While Tyrus Wong now is remembered as a well-respected Chinese-American artist, “in 1938 he was a man who needed a job,” Canemaker said.

He got one at The Walt Disney Co. that paid $35 per week but landed him in the wrong position, according to Canemaker.

This slide, which shows a man feeding a whitetail deer that was one of many deer taken from Maine to California by the Walt Disney Co. for artists to study for the movie “Bambi,” was part of a presentation Tuesday by film and animation historian John Canemaker during a Maine International Film Festival event at the Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville.

Wong was hired as an “inbetweener,” an anonymous draftsman who drew the animations in between key frames drafted by the lead artists. Inbetweeners used illuminated animation boards and would sometimes do 24 drawings for one second of animation.

“I hated it,” Tyrus told Canemaker. “I told my wife my eyes were killing me.”

During his time off, Wong drew landscapes peppered with deer and showed them to art director Tom Codrick, who realized Wong was in the wrong department.

The initial setting in the movie had too much detail, Canemaker said, and threatened to detract from the animators’ work. After winning the role of lead artist, Wong took the opposite approach in the paintings he was asked to make for each important moment in the movie.

“I tried to keep the thing very, very simple and get the atmosphere and feel of the forest,” he told Canemaker, adding that the enthusiasm of the artist was more important than the detail.

Wong painted in pastel and often on tiny pieces of paper, sometimes as small as 2 inches by 2 inches. His influence is apparent throughout the frames of the movie, Canemaker said, in the simplicity of the backgrounds and the variations in colors that mirror the emotions of the characters.

Wong was fired during the Disney animators’ strike in 1941 despite siding with the studio, but the company later recognized him for his important work on the film.

He moved on to work for Warner Brothers Studios for 26 years as a production illustrator, painting conceptual designs of sets for various films, including those in one of his favorite genres, John Wayne westerns.

After retiring in 1968, Wong continued to create art, including Hallmark greeting cards, paintings, murals, kites and painted ceramics that were sold in department stores. He died at the age of 106 in December 2016.

“Love what you do, and life will reward you,” Wong told Canemaker.

Madeline St. Amour — 861-9239

mstamour@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @madelinestamour

Send questions/comments to the editors.