Farming isn’t an easy life, but in many ways today’s farmers have it better than the hardscrabble folks who settled this state a couple of centuries ago.

Yes, some of today’s farmers may still use real horsepower instead of the mechanical kind, but they can also advertise their vegetables on Instagram and plan their plantings with computer software.

Sometimes it’s good to glance in the rearview mirror to see how far we’ve come. Maine has several good agricultural museums that will let you do just that. Here’s a sampling:

Sheri Leahan, the director at the Norlands, in costume as her character, Ora Pratt, who was another neighbor to the Washburns in the 1800s.

THE WASHBURN-NORLANDS LIVING HISTORY CENTER

290 Norlands Road, Livermore; 897-4366; norlands.org

HOURS: Open 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays in July and August.

COST: $10 adults, $6 ages 12 and under; $25 family rate for two adults with two or more children under 18.

It’s a lovely drive to this museum, once you get past the Auburn strip malls lining Route 4. You’ll make your way through green, rolling hills, and past old stone walls surrounding farms you just know have been in the family for years. But it also feels a little like you’re visiting “The Village,” from the M. Night Shyamalan movie where people live in an isolated community tucked away in the forest, thinking it is still the 19th century.

The Washburn-Norlands center was the family homestead farm of Isaiah Washburn Sr. Washburn and his wife, Martha, raised 10 children who went on to become politicians, generals, industrialists, ambassadors, and the founders of Gold Medal Flour. The museum’s volunteers dress up in period-appropriate clothing and take on the personas of the Washburns and others who lived in the community in the late 1800s.

Lucille Lavoie with a a quill and ink at the Norlands.

The first person I met was “Hannah Coolidge,” who once lived near the Washburns but was now in their farmer’s cottage kitchen baking oat cakes in the wood stove. (Her 21st-century name is Lucille Lavoie.) She offered me one, and we started chatting about life in 1870.

Hannah was wearing a floor-length dress with a green skirt covered by an apron, and one of those scrunchie-style bonnets women wore back then. I asked her about the bonnet, and she said it helped to keep her hair clean.

“In 1870, you don’t take a bath every day,” she said. In the wintertime, she pointed out, her house only has heat in the kitchen.

“So when I take a bath on Saturday night in front of the wood stove, if I wash my hair and I go into any other part of the house, my hair freezes,” she said. “So all week we wear something on our head to keep our hair clean.”

Hannah asked me to sign a petition to the Legislature humbly begging and beseeching Gov. Joshua Chamberlain and the state Legislature to give women the vote. It was my first time writing with a genuine quill pen dipped in a bottle of ink.

Next I wandered onto the porch of the main house, where “Mrs. Horr, visiting from Lewiston” was waiting to guide me. (Her real name is Tizz Crowley, and she’s a former Auburn city councilor who has fallen in love with this whole living history thing.)

I sat on the porch enjoying the cool breeze while Mrs. Horr gave me a short lesson on the importance of the Washburn family.

“Through our history, we know about the Rockefellers, the Carnegies, the Cabots, Lodges and Kennedys and we think ‘Oh what wonderful things they did,” she said, “but from a political and an industrial perspective, the Washburn family had just as great an influence.”

Tizz Crowley reads on the porch of the the Norlands mansion while waiting to give a tour of the house.

Just inside, in the central hall, we admired a magnificent hat-and-umbrella stand from Paris and two large portraits of William Drew Washburn and his wife Elizabeth, whose original furniture is displayed in the hall. Mrs. Horr kept talking about the Washburns and their neighbors as if they were still alive, and so when she said I would be meeting Adele Washburn (and admiring her beautiful red dress) in the next room, I expected to find another volunteer dressed up in old-fashioned clothes. Instead, I got “introduced” to a portrait.

But that just illustrates how immersed the volunteers are in their characters, and how fun it is to get caught up in it all.

Museum director Sheri Leahan says the museum gets 3,500 visitors a year, including a lot of students on school field trips. Among the museum’s programs for students is one with a “school marm” in the one-room school house down the road from the main house, and another with a couple focused on farm life. In the farm programs, the students are assigned new identities as members of a 19th-century farm family.

“They are assigned a name of someone who actually lived in this area,” Leahan said. “They are either part of the Waters family, who lived right up the hill, or they become a Pray family member. The Prays have a farm just on the other side of the church.”

The kids do farm chores and help make “the nooning” – a noontime meal of soup.

Whether you have kids or not, visiting this museum is the most fun way imaginable to have a history lesson and learn about Maine’s rural past.

If you go, say hi to Hannah Coolidge and Mrs. Horr for me.

The Temperance Barn at Narramissic Historic Farm was built in the 1830s by George Fitch, son-in-law of the house’s original owner, William Peabody. According to historians the 40 by 60 foot structure was named the Temperance Barn because it was raised during a period of religious revival, without the barrel of rum that was usually part of such occasions.

NARRAMISSIC, THE PEABODY-FITCH FARM

46 Narramissic Road, Bridgton; 647-3699; bridgtonhistory.org

HOURS: Grounds are open year round, but the house is open only in July and August, 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. Thursday to Saturday. You can also call the Bridgton Historical Society and make an appointment.

COST: Free, except during special events, but donations are encouraged.

Narramissic is said to be an Abenaki word that means “hard to find,” and although this homestead was built in 1796, the description still applies in the 21st century, says Ned Allen, executive director of the Bridgton Historical Society. This 25-acre New England hill farm (it was originally ten times the size) is “kind of remote and isolated,” he said, tucked away where the only sign it’s 2017 are power lines strung along the road.

But the mountain views from here are, he says, spectacular.

The museum includes the historic home of a once prominent local family, a large barn, a blacksmith shop, and grounds for hiking and picnicking. The house was built in 1797 by William Peabody. His daughter Mary and her husband, George Fitch, moved in during the 1830s, eventually building the “Temperance Barn,” so called because when the barn was raised, they didn’t serve the traditional barrel of rum.

The Temperance Barn is known for a particular feature of its construction: the “English tying joint,” a complex joint located where the roof line meets the horizontal beams. The joint originated in Medieval England – it can still be seen in English barns dating back to the 1200s – and was brought here by the colonists.

“It’s a really great example of rather sophisticated joinery,” Allen said.

Descendants of the Peabody-Fitch family lived in the house until 1938, Allen said, when a woman from Rhode Island bought it to use as a summer home. When she died in 1987, she left the property to the Bridgton Historical Society.

“In the house, most of the furnishings are original to the family,” Allen said. “We have wonderful memoirs from Edwin Fitch, who grew up there in the 1840s and 1850s, before he went away to the Civil War, with really rich history of the daily life of the family – how they planted things and shared chores, stories about the barn.”

Visitors to the museum can buy a copy of Fitch’s journals, called “90 Years of Living.”

Naramissic has a display of plows and other farm implements, as well as some of the equipment used by Mary Fitch, who was known for her cheesemaking.

The museum gets only 300-400 visitors a year, which Allen chalks up to the fact that people just don’t know about it. It’s popular with locals, though, who go there to hike and walk their dogs. The museum also hosts events such as weddings, family reunions and bluegrass festivals.

This summer Lucas Damon, a working blacksmith from Naples, will be on site one day a week and at special events. On July 22, the museum will hold a “Celebration of Traditional Arts” at the farm. The blacksmith will be there, as well as an herbalist who will talk about the history of herbal medicine. David Allen from Stone Point Studio in Sebago will demonstrate traditional granite-splitting techniques, and Greg Marston, a master cabinet maker, will give a talk on how to recognize authentic antiques. There will be children’s activities, house tours, a nature walk, and a hike to the quarry where the granite for the Temperance Barn was harvested. The historical society will provide lunch and light refreshments.

The event will be held from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and costs $5 for adults and $3 for ages 5 to 16. Children under that age get in free. Allen said families will not have to pay more than $15 total admission.

The Page Farm & Home Museum in Orono.

PAGE FARM & HOME MUSEUM

Portage Road, University of Maine-Orono campus; 581-4100; umaine.edu/pagefarm

HOURS: Open year round, 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday. Closed holidays, as well as the week between Christmas and New Year’s.

COST: Field trips cost $2 per student to cover the cost of materials, but for the rest of us this museum is free.

The first thing you see when you walk through the door of the Page Farm & Home Museum is a wood-and-metal contraption that, at first glance, looks like something a farmer would use to mill grain or shear the kernels off a corn cob.

Not so fast, city slicker.

Thanks to the young man who was watching over this museum on the University of Maine campus in Orono on the day I visited, I learned that it was a bone crusher, used to grind animals’ bones into meal for fertilizer.

Like many sustainably-minded Mainers today, farmers who lived a century ago wasted nothing.

The Page Farm & Home Museum is a hidden gem tucked into an eastern corner of the campus. It’s a good bet you’ve never heard of it, though it has been here since the late 1980s. The main museum, located in a beautiful three-story, 1833 post-and-beam barn – the last original agricultural building on campus – documents farming and rural life in Maine from 1865 (which marks the beginning of land grant universities) to 1940, when electricity radically transformed farming and rural life.

“It was a great transitional period where people moved to the cities to work in mills, and farms in rural Maine went from being small family farms to being consolidated into large industrial operations,” says Patricia Henner, director of the museum.

Artifacts are displayed on two floors of the barn. Be sure, as you walk on the wooden plank flooring, to look up. Sleighs and carriages are stored above your head, in the gorgeous rafters. It’s hard to believe, but the university once held classes in this barn.

The museum includes some exhibits you’d expect, such as a collection of agricultural tools used on the farm. But have you ever seen a horse dental kit? Or how about an ox sling made by a blacksmith around 1800, used to hoist the animal when it’s getting new shoes? Turns out oxen can’t balance with one leg lifted, the way horses do, hence the phrase “clumsy as an ox.”

But this museum offers more than tools and “guess what this thing does?” Just as today’s farmers take on other jobs to make ends meet, so did their forbears, and the musem has mini-exhibits on the many industries they dabbled in – forestry, ice harvesting, spinning and weaving, woodworking and maple sugaring. (Check out the hand-hewn sap trough that dates to the 18th century. It’s one of Henner’s favorite pieces.)

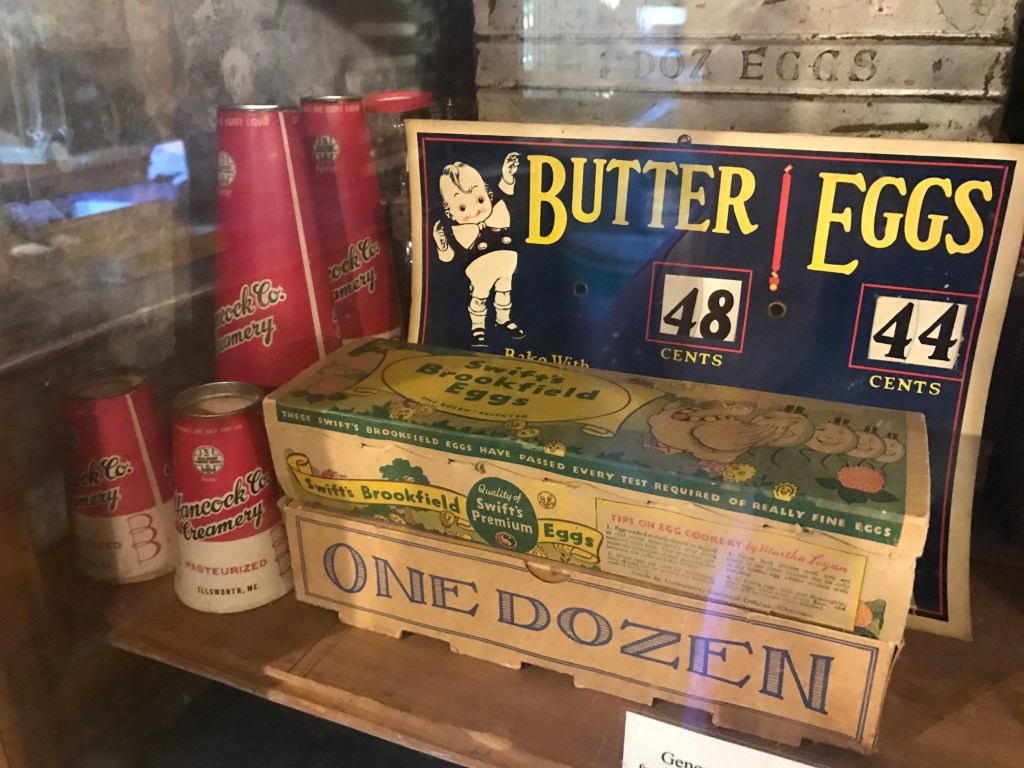

Some rooms are designed to take you back in time, such as the re-creation of an old-fashioned general store. The counters came from the Hodsdon General Store in Corinth, open from 1856-1912. A stunning floor-to-ceiling oak ice box from L.P. Cole’s General Store in Prospect Harbor is filled with dairy ephemera, including an old butter-and-egg sign (butter 48 cents, eggs 44 cents a dozen), and egg cartons and cream containers in top-notch condition. (Do you suppose Mainers complained about those prices the way they do about $5/dozen eggs at today’s farmers’ markets?)

Stop by the parlor, the bedroom and Brownie’s Kitchen, named after Mildred “Brownie” Schrumpf, a home economist who taught at the University of Maine and was dubbed the state’s “Unofficial Ambassador of Good Eating.”

One showstopper, just past the bone crusher, is a 1920 red Model T Ford Wagon used by Musterfield Farm in South Parsonsfield to deliver milk from house to house. The wagon was also used to transport “The Singing Smiths” – a Von Trapp-style family of entertainers – to country dances in Grange Halls all over southern Maine so they could supplement their farm income by playing music and singing. That’s one way of making ends meet that hasn’t gone out of style.

When you’re done in the big barn, wander outside to explore the carriage house and blacksmith shop (both replicas built in 2003), a quarter-acre heirloom garden, and a one-room schoolhouse that stood in Holden from 1855 to 1950. The schoolhouse is classic: A portrait of George Washington hangs on the wall, and a school bell and inkwell sit on the teacher’s desk. (Think phones in the 21st-century classroom are a problem? Nineteenth-century school marms also had to deal with troublemakers, as you’ll see by the writing on the blackboard: “I will not play with marbles in class.”)

The Page Farm Museum got about 12,000 visitors last year, plus 3,000 visits from school kids on educational tours, where they might play 19th-century games, do some weaving, or craft a cornhusk doll.

Let’s hope they keep them away from that bone crusher.

A greenhouse at Raitt Farm made of windows from the property dating back to the 1800s.

RAITT HOMESTEAD FARM MUSEUM

2077 State Road, Eliot; 748-3303

HOURS: Special events only, or call for appointment. On July 28-30, the farm will host the 22nd Annual Eliot Antique Tractor and Engine Show.

COST: The Antique Tractor and Engine Show costs $7; children 12 and under get in free.

The 33-acre Raitt Homestead is actually a museum-in-progress. Most of its farm equipment – antique tractors, an apple cart, a cranberry winnower – are stored away for now and brought out only for special events or to show the curious who call ahead. The caretakers, members of the Raitt family, will do private tours for schoolchildren, teaching them about farming history.

The former dairy farm and brick yard date back to 1896. Tom and Lisa Raitt, the husband-and-wife caretakers of the property, represent the fourth generation of the family to live there, although the farm no longer belongs to them – it’s now a non-profit entity that supports itself with fundraisers and the help of volunteers. The upcoming Eliot Antique Tractor and Engine Show is its largest annual fundraiser.

Lisa Raitt says they hope to have museum-quality buildings some day for exhibits, and to open the farmhouse for tours at least a couple of days a week.

“We have so many different collections, but we have no real space to display them,” she said.

During a renovation six years ago, contractors found a powder horn and an 1858 Beals Remington Revolver hidden in the eaves of the farmhouse.

Meanwhile, until the homestead can build up its infrastructure, it is holding events like the tractor show, demonstrations in its blacksmith shop, and canning classes. The farm is a wedding venue, and businesses hold employee picnics there.

Volunteers clear nature trails on the property, and are building a brick walkway to the greenhouse using 1800s-era bricks from the old Raitt brickyard. The greenhouse itself is made from 1800s-era farmhouse windows.

At the upcoming tractor show, visitors will see some large equipment from the Midwest as well as gear from Maine and New Hampshire, Raitt said. The farm has a 1901 Hildreth double-sided woodsplitter, and a rare, 40-horsepower Reid oil field engine from Pennsylvania will be on display.

MAINE HERITAGE MATTHEWS MUSEUM

Common Road, Union (on the Union Fairgrounds); 542-2379;

HOURS: Open in July and August, 12 to 4 p.m. Wednesday to Saturday. Open by appointment only in June and September.

COST: $5 for adults and $3 for seniors and children under 12. Admission is free during the fair, which will be held this year Aug. 19-26.

This museum is a great choice if you have someone in your family who is just not into plows and pickling jars.

This museum has 10,000 items on display from Colonial times up to about 1950. If you’re a gearhead or farming fan, you can check out the museum’s farm tools and machinery, the poultry display, the blacksmith shop and the cooper shop while the rest of the family explores the kitchen, the bedroom, the carriage house (check out the horse-drawn hearse and the 12-foot-long sled that can hold six riders), the vintage clothes, and the one-room schoolhouse transplanted from the town of Washington.

Best of all, this museum not only displays Moxie artifacts, it has a whole Moxie wing! Dr. Augustin Thompson, the inventor of Moxie, was born in Union, and so locals have assembled 1,000 Moxie-related items for your viewing pleasure, including a 32-foot wooden Moxie bottle – the only one in existence.

Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Send questions/comments to the editors.