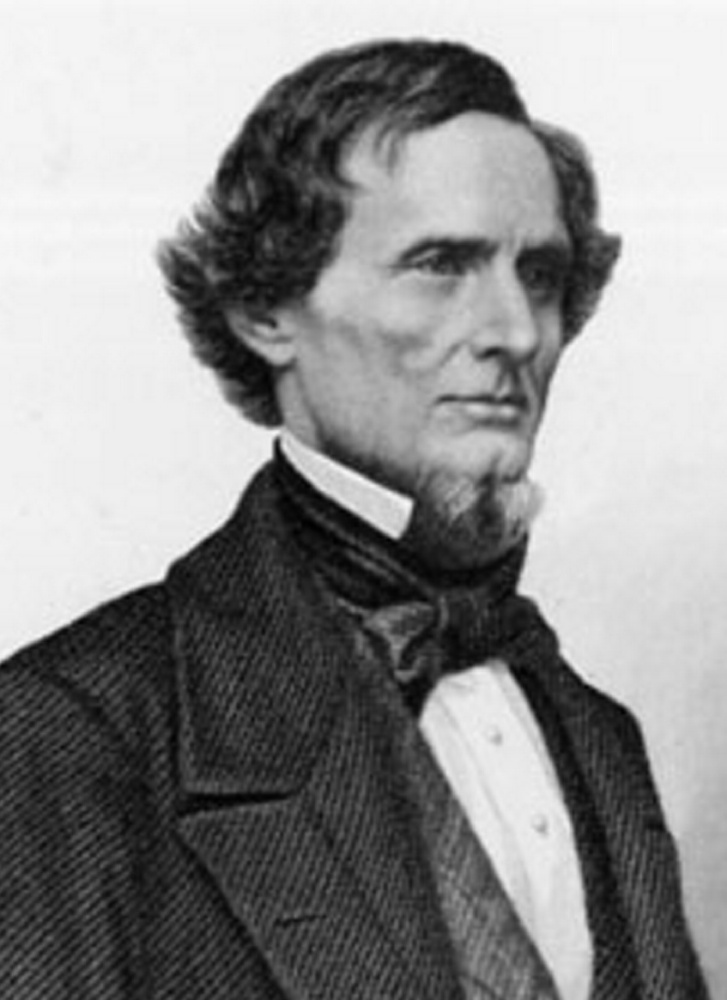

MONTGOMERY, Ala. — Schoolchildren who visit the First White House of the Confederacy learn that its famous former resident, President Jefferson Davis, was leader of a “heroic resistance” who was “held by his Negroes in genuine affection as well as highest esteem.”

Such ideas, once mainstream Southern thought, have largely been abandoned by historians. But they are still part of the message at this state-supported museum in Alabama’s capital city that hosts thousands of grade school children from different ethnic backgrounds on field trips every year.

Some critics say presenting discredited notions about the Confederacy at the antebellum home where Davis lived in the early months of the Civil War helps perpetuate a skewed version of the past and shouldn’t be supported by Alabama tax dollars.

“You’re essentially giving money to push historical narratives that we haven’t heard since the Klan era in the 1920’s,” said Heidi Beirich, director of the hate-watching Intelligence Project at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

The museum perseveres in a newer era when many Confederate memorials across the South are being re-evaluated. South Carolina lowered the Confederate flag at the state Capitol after a 2015 mass murder at a black church in Charleston. And last month, New Orleans officials took down a 35-foot granite obelisk that honored whites who tried to topple a biracial Reconstruction government installed in New Orleans after the Civil War.

On a recent trip to the Montgomery museum, fourth graders from rural Wilcox County in southern Alabama trudged up a nearly 200-year-old staircase and into the Relic Room, where a painting of Gen. Robert E. Lee hangs amid the four flags of the Confederacy.

Tour guide Robert Wieland tells the children the room was formerly called a “shrine.”

The pupils heard about the importance of the South’s cotton economy and learned how to spin raw clumps of the stuff onto wooden spools, but were told little about the slaves whose forced labor drove the textile industry.

Tours and literature there make little mention of African Americans, except for a copy of “Jim Limber Davis: A Black Orphan in the Confederate White House,” an illustrated children’s book about a boy adopted by the Davis family. The book is displayed across from a framed image of some of the South’s most prominent leaders titled “Our Heroes and Our Flags.”

Selma Democratic state Sen. Hank Sanders said the house, which in recent years cost Alabama taxpayers more than $100,000 a year to operate, presents a history that ignores African Americans.

“What I would like to see is the whole story be told from all sides,” he said. “Black history has been whitewashed.”

In response to such criticism, representatives of the museum ask why they should have to tell students about the evils of slavery. “They just know it,” said Gibbs Davis, a member of the nonprofit group that solicits donations for the house and maintains it.

The Confederate White House is only one stop on the trip to Montgomery that Alabama fourth graders traditionally take as part of their history education. Some groups choose to spend more time at civil rights sites such as Martin Luther King Jr.’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church or the Rosa Parks Museum.

The two-story home that served as executive residence for the Southern states in the Spring of 1861 still has its defenders.

Mary Dix is associate editor of “The Papers of Jefferson Davis,” a collection of approximately 100,000 Davis-related documents. She pushed back on criticism, saying Davis was a good person who wanted to end slavery on moral grounds but considered it necessary for the Southern economy.

Dix also said there is documented evidence that Davis befriended a “man-servant” over cigars during a journey into the uncharted Midwest.

A history pamphlet at the First White House of the Confederacy echoes Dix’s sentiment. “Jefferson Davis believed ‘the peculiar institution’ a temporary necessity in developing the cotton economy of the South on which New England textile industry depended,” their history pamphlet reads. It says Davis believed whites were preparing Africans for freedom by “submitting” them to Anglo-Saxon culture and Christianity.

Activists say presenting a rosy picture of the Confederacy obscures what life was really like for slaves.

Send questions/comments to the editors.