AUGUSTA — Terrence “Terry” Marks has kidneys that are twice the normal size and are doing less than a quarter of the work they should be doing to filter toxins from his system.

Symptoms of his polycystic kidney disease – now at stage 4 – forced the West Gardiner man from his job in November 2015 as part of a state highway maintenance crew that plowed roads in winter and did other jobs in the summer.

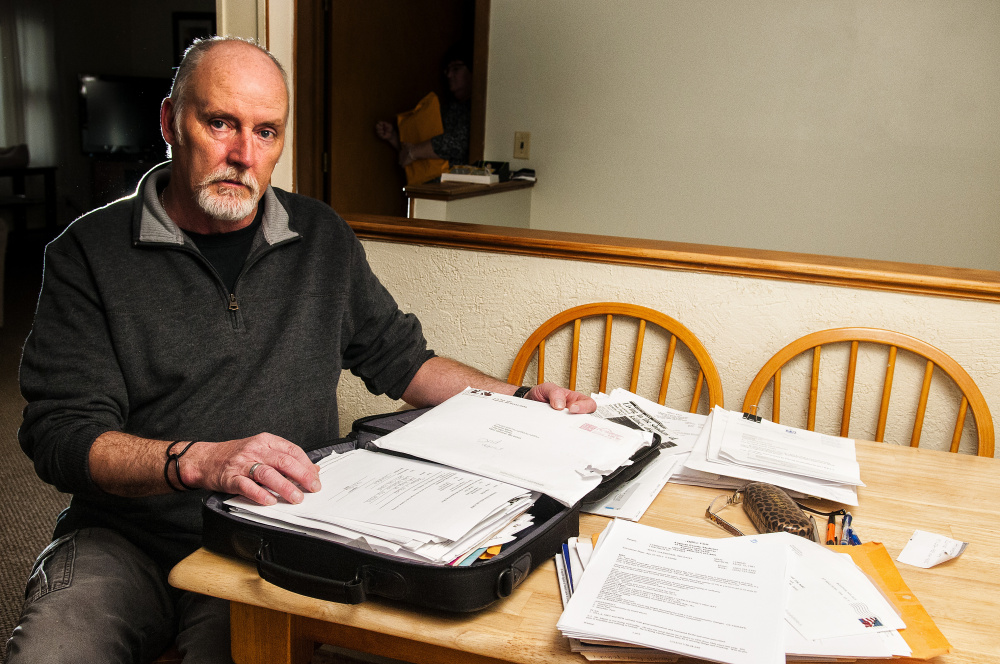

Marks, 55, has seen his disability retirement application rejected by the Maine Public Employees Retirement System, has been declared ineligible to collect a military retirement because his wife earns $29,000 as a clerk for the town of West Gardiner, and is ineligible for Social Security disability benefits.

He went to the State House on Friday morning to speak in favor of L.D. 176, a bill that he hopes will change the laws regarding state disability retirement benefits.

But the Legislature’s Appropriations and Financial Affairs Committee only briefly considered the bill before agreeing to carry it over to the next session. Marks was out of the hearing room when the public was invited to comment, and he missed the opportunity. In fact, no one spoke about the bill, which is a concept only and lacks specific language.

‘NO HELP IN THE STATE SYSTEM’

But he and his wife, Tina Marks, still plan to support a law change so others don’t run into similar problems.

“There’s no help in the state system,” Terry Marks said Thursday as he considered what he wanted to tell the committee. “My money is sitting in the state retirement system. My money’s there. I’m getting nothing. My future retirement money’s sitting there.”

Marks was terminated in November 2015 because he was no longer physically able to perform his job after 19 years and 11 months working for the state.

For a year, the family was OK financially because he had purchased income protection insurance, but that support ended in November 2016. Now things are much tighter.

Although he has medical insurance through his wife’s job, he said: “There’s lots of bills coming in that aren’t covered by insurance. I have an old junked-out pickup truck. There’s the phone, lights, heating. Once there’s no paycheck, we’re scrimping, downsizing, everything you can imagine we’re trying to streamline.”

They feel powerless.

“This isn’t my master plan,” Marks said. “We were going to retire and venture out and do the day trips. We were going to enjoy our retirement. Our plan was not to be sick. We were going to buy a camper and go camping on weekends and travel around the state of Maine. My retirement has been altered. My plan wasn’t to get sick and end up suffering in end-stage kidney failure.”

He got news of his latest denial from the Maine Public Employees Retirement System on Wednesday.

According to Michael Colleran, general counsel for MainePERS, Marks’ case now will be considered by the system’s board of trustees. If the board upholds the hearing officer’s denial, then Marks’ only appeal would be to a Superior Court judge.

Data from MainePERS indicates that 82 of the 121 disability applications handled in 2016 were denied initially. It also shows that of the 73 appeals completed that year, 23 were granted.

Sen. Shenna Bellows, D-Manchester, who is not on the committee but who tried to aid the Markses, said afterward, “It strains credibility to me that 62 percent of the applicants for disability can be denied.”

She said she worries about how the families can survive.

“I would like to see something done that will try to make the system work for the people it’s designed to serve,” she said.

Just before the committee’s consideration of L.D. 176, introduced by Rep. Robert A. Foley, R-Wells, MainePERS and the MainePERS Disability Retirement Task Force made presentations to the committee that appeared to address some of the concerns Marks and others have.

Sandy Matheson, executive director of MainePERS, noted that 1,300 of 38,500 retirement member are on disability; the others are on service retirement. Another 51,000 are active members, paying into the plan.

She noted that members of MainePERS “experience varying levels of difficulty and frustration when applying for disability retirement.”

Specifically, Matheson said, the statute limits the MainePERS benefit to permanent disability.

RETIREMENT NOT FOR DISABILITY

“We know there’s a misperception of what our program is that really causes a lot of hardship and heartache for people,” Matheson told the committee.

She said the task force looked into the costs for long-term disability insurance, which would fill in when the short-term income protection ends.

“We’re hoping to make it an opt-out, so people are aware there could be a gap in income and don’t think of our plans as disability insurance,” she said.

Rep. Brian Hubbell, D-Bar Harbor, who serves on the committee, said: “I’m convinced we need to do that. We have to have some system to tell employees what our disability retirement program is and isn’t.”

Matheson said later that MainePERS is trying to refine its internal process to educate members and employers that the retirement system is not for long-term disability.

“You retire because you’re permanently disabled,” she said.

She told the committee that problems arise when members essentially apply too soon, when they find work difficult but are not yet permanently disabled.

Matheson also indicated that Foley’s bill is a placeholder should the agency need changes in the law.

Sen. Roger Katz, R-Augusta, also presented a bill to give state disability retirement benefits to someone who becomes disabled after leaving state service, who is ineligible for Social Security disability and who prevails in or settles a claim under the state’s Whistleblowers’ Protection Act.

The first person to testify in favor of the bill was Sharon Leahy-Lind of Portland, who meets all those requirements.

In 2013, Leahy-Lind, who was director of the Division of Local Public Health at the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, disclosed that she was ordered by her superiors to shred documents related to competitive grant awards in the Healthy Maine Partnerships program. The documents shed light on irregularities and possible illegal activity in the way certain grants were awarded.

She later filed a whistle-blower complaint in federal court alleging retaliation for refusing to shred the documents. The lawsuit was settled.

Leahy-Lind said bona fide whistle-blowers should not be denied benefits. She told the committee she had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer after leaving state service and that the bill could potentially benefit her and protect future whistle-blowers.

“I’m not here today to seek your sympathy,” she told them. “What I’m afraid of is to live with no income, continue to liquidate my assets and leave my daughters with debt.”

Friends and former co-workers of Leahy-Lind spoke in support of the bill as well.

Betty Adams can be contacted at 621-5631 or at:

badams@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.