AUGUSTA — For the supporters of the Colonial Theatre, the vision is so clear.

In 27 months or so, the restored historic theater with a new annex at the north end of Augusta’s historic downtown will offer space for a variety of performances, events and community uses along with an art gallery and restaurant that will raise the profile of the arts in the capital region.

That’s a lot of weight for one project to carry, but Richard Parkhurst, who is heading the redevelopment efforts, strongly believes it can happen, it should happen and it will happen.

“It’s essential,” Augusta Mayor David Rollins said. “It’s absolutely essential to the vitality of the city.”

As it now stands, the Colonial Theatre is a brick shell with a new roof enclosing a space whose distinguishing features include a stage, a cantilevered balcony and a big hole in the floor.

As ambitious as the redevelopment plans are, they are not unique.

Across the United States, communities have backed efforts to renovate and revitalize their historic theaters.

“It creates economic development and it drives business,” said Ken Stein, president and chief executive officer of the League of Historic American Theatres. “But I think most people, when they are talking about show business, focus on the show and forget the business.”

What a theater is uniquely able to do, Stein said from his office in Austin, Texas, is draw people to a destination and prompt them to spend money.

The League of Historic American Theaters is a nonprofit that works to sustain historic theaters in the United States and Canada and offers training and resources to make historic theaters sustainable businesses.

“People are making a choice and making plans around a choice,” Stein said. “They’re paying for a meal, parking, baby sitters and going shopping to dress up maybe. When we do economic impact studies on theaters, we take that into account.”

Stein saw it when he was working to revive a historic theater in Austin. He and his staff watched as the plywood came off the windows of neighborhood shops and restaurants start to move in and partner with the theater for events. “It happens again and again,” he said, and it doesn’t matter whether the theater produces its own shows or hosts music and comedy or shows movies.

Stein has developed, with the help of a model by Americans for the Arts, a snapshot of the effect of historic theaters. A single historic theater in a city with a population of less than 50,000 can sustain 32 full-time equivalent jobs, can create $1.1 million in total expenditures and can generate $96,000 for local and state governments. It also can add $684,000 to household incomes.

“One thing holds true,” he said. “Theaters that are open and operating, as long as they have a good business plan in place and they know what the community is looking for, they become fantastic revenue generators.”

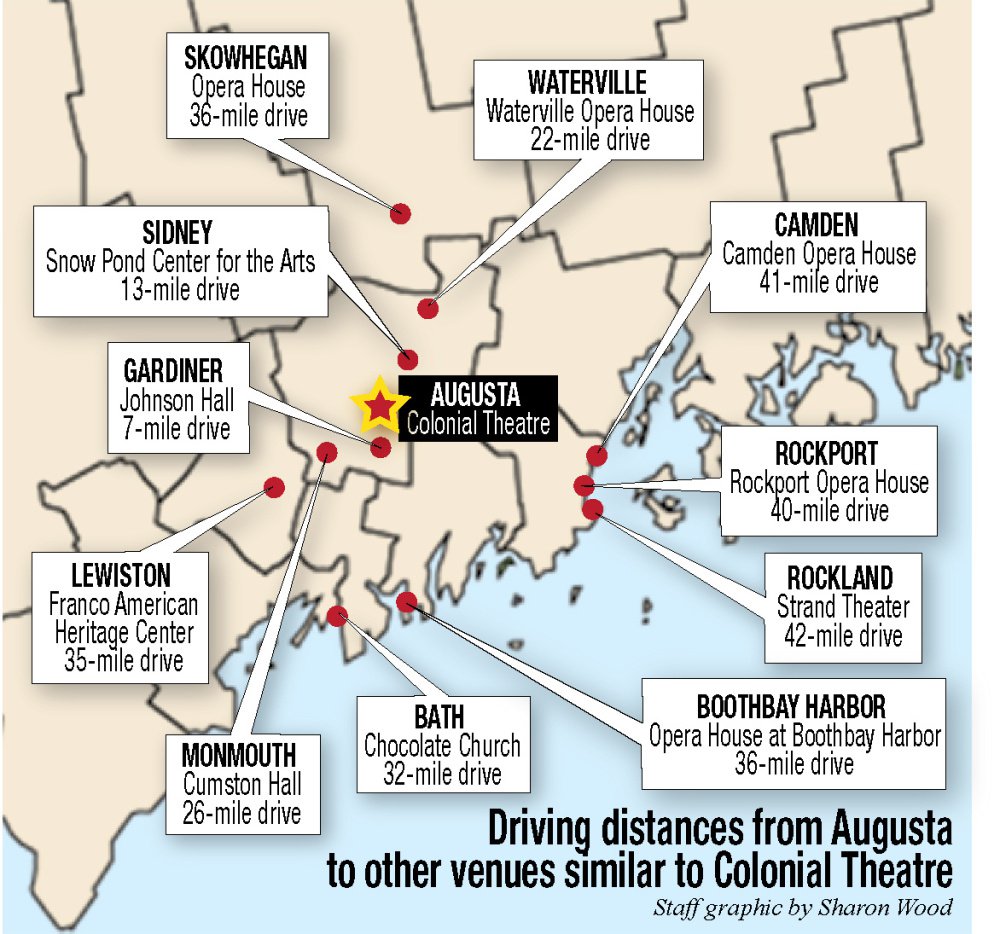

Across central and midcoast Maine, supporters and funders have backed theater projects ranging from the Chocolate Church in Bath and the Franco American Heritage Center in a former church in Lewiston to the Snow Pond Center for the Arts in Sidney and the Johnson Hall Performing Arts Center in Gardiner. Boothbay Harbor, Rockport, Camden, Skowhegan and Waterville all have historic opera houses. And Rockland has the Strand, which like the Colonial, started as a movie theater.

The experiences of two of these theaters shed light on the effect a historic theater can have.

ROCKLAND TURNAROUND

Two and three decades ago, it was “Camden by the Sea and Rockland by the Smell.”

The coastal Knox County fishing community was not the city it is today.

“It was the worst place in the world,” Jessie Davis said.

When she was growing up on Mount Desert Island, Davis passed through Rockland on the way to visit friends in Owl’s Head.

“If you told me I would love it here, I would not have believed it,” she said.

Now Davis lives in Rockland with her family, and she’s the executive director of the Strand Theatre on Rockland’s Main Street. While the city’s revitalization started long before the Simmons family bought and renovated the theater, the Strand has played a role in its success.

“It’s ingrained in Rockland becoming an arts destination,” said Audra Caler Bell, Rockland’s Community Development director.

Rockland has long been home to the Farnsworth Art Museum, which has undergone an expansion. The Center for Maine Contemporary Art relocated there from Rockport in 2015, and Rockland’s Main Street is lined with art galleries, shops and restaurants.

“When you have a theater or performing arts venue, it brings people to the city at a time when you want it to be more vibrant,” Caler Bell said.

Most retail shops tend to close for the day around 6 p.m., but evening events bring people downtown to support restaurants and bars. For Davis, the Strand’s lighted marquee signals that something is going on in the city and adds a level of attractiveness to the area.

“I can say this because I hear it all the time,” Davis said. “The Strand is a real quality-of-life enhancer for the community, certainly for those who take part in the programs.”

Rockland businessman Joseph Dondis built the Strand six months after the catastrophic downtown fire of 1922, which leveled four business blocks. For eight decades, the Strand hosted movies, dance recitals, vaudeville shows and theatrical productions. It outlasted two rival theaters by the 1960s and added a second theater space by sectioning off the balcony.

Last year, the 350-seat theater welcomed 39,000 people from 200 communities for 179 events. Those events include the Camden International Film Festival in September; the Camden Conference, which was held last weekend; movies; live music performances; and live-streamed performances from the Metropolitan Opera and the National Theatre.

“We haven’t invested in studies for the economic impact of the Strand, but there’s a lot of evidence that the theater takes Rockland up to the next tier for small cities,” Davis said.

‘MAGICAL SPACES’

In Waterville, which like Augusta has a history as a mill town, the $5 million worth of renovations at the Opera House in 2013 ushered in 21st-century technology, new balcony seating, restored woodwork, new flooring, and a new set shop, dressing rooms and freight elevator.

“The economic impact of a thriving historic theater can’t be overstated,” said Kimberly Lindlof, president and chief executive officer of the Mid-Maine Chamber of Commerce in Waterville. “It brings economic vitality to downtown and the whole region.”

Lindlof was chairwoman of the Waterville Opera House board of directors during the capital campaign and build-out, when the opera house was closed for nine months. Her board at the Chamber of Commerce supported her role on the opera house’s board and the time that entailed because of the economic impact it has on the community.

When she was a child, Lindlof said, downtown Waterville was a retail center filled with department stores. But as department stores have consolidated or closed and strip malls have drawn retail activity closer to Interstate 95, downtown Waterville had to recreate itself.

Through Waterville Creates!, which includes the opera house and other cultural organizations, such as the Colby College Museum of Art, the Waterville area now is being promoted as an arts destination. The Maine International Film Festival, which will celebrate its 20th anniversary in 2017, likewise draws visitors and national attention over the course of the 10-day event. In its history, it has honored actors such as Gabriel Byrne , Glenn Close and Sissy Spacek.

“If the Colonial Theatre in Augusta does anything like the Opera House does in Waterville,” Lindlof said, “it should have a very good impact.”

That’s what Michael Hall is hoping for.

Hall, executive director of the Augusta Downtown Alliance, said he expects the Colonial Theatre, like Gardiner’s Johnson Hall, will draw people in from across the region.

Right now, he said, a cultural void exists in Augusta, which is the only capital city in the country that doesn’t have a performing arts center.

“We don’t want to be ‘Disgusta’ any more,” he said. “We want to compete with other capital cities.”

From an economic development standpoint, it will bring more tourism into Augusta, Hall said, and it could fuel interest in developing a boutique hotel on Water Street. Even though Augusta’s population is relatively small, hundreds of thousands people live within an hour’s drive of Maine’s capital city.

The 800-seat theater will be able to draw acts that will in turn draw people who will travel to Augusta and spend money, he said, in restaurants and bars.

Those expectations mirror the projections provided by the League of Historic American Theatres.

But there is an added element, Stein said.

If a historic theater is open and operating, it’s because of a love story between the community and its theater, he said.

“These are magical spaces,” he said. “When you get a community to fall in love with one of these buildings, it won’t go away anytime soon.”

Jessica Lowell — 621-5632

Twitter: @JLowellKJ

Send questions/comments to the editors.