Ku Klux Klan fliers distributed in Freeport and Augusta last week shocked residents and raised the specter of the hate group tapping into anti-immigrant sentiment that’s swirling in Maine and the nation.

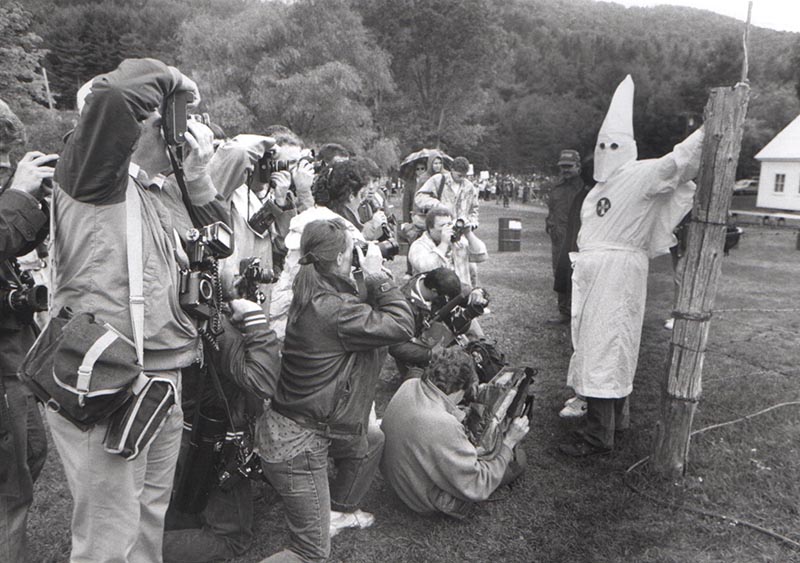

There have been other attempts to organize the Invisible Empire of the KKK in Maine, including a rally in Rumford in 1987 and a march in South Portland in 1988. In both cases, protesters against the Klan far outnumbered the few participants. A cross burning in Bethel in 1982 inflamed public outrage.

It wasn’t so long ago, however, that hundreds of Mainers, sometimes thousands, gathered in public halls in Saco, Portland, Hallowell and Rockland to hear polite lectures on the principles of the KKK and the virtues of pro-Protestant “Americanism.”

Across the state in the 1920s, Christian crosses were burned in Sanford, Lewiston, Gardiner, Dexter and Stockholm, attracting crowds and inspiring fear amid the economic recession, nativism and isolationism that followed World War I. For several turbulent years, membership in the KKK exploded to an estimated high of 8 million in the United States, including northern and western states such as New Jersey, Michigan, Oregon and California.

By 1923, rapid growth of the KKK in Maine gained national attention, prompting the Boston Herald to publish a six-day front-page series of articles that noted 20,000 Klan robes had been sold here within a year or so. In Portland, prominent residents established a clubhouse on Forest Avenue, where 1,500 Klansmen witnessed the initiation of 400 new members one Saturday in August as about 10,000 curious citizens watched from side streets.

And in 1924, when as many as 40,000 Mainers had joined the KKK, the organization was a driving force in electing Republican Gov. Ralph Brewster on a tide of anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic sentiment.

“The Klan is reborn in a new form in the 1920s,” said Earle Shettleworth, Maine state historian. “It’s not just a Southern institution anymore. It gains a national prominence, and here in Maine it was a very controversial political issue.”

Shettleworth said the way Mainers responded to the KKK nearly a century ago offers insights and lessons still relevant today, when Klan activity is on the rise nationally. The KKK is a largely secretive society that was organized in the South after the Civil War to assert white supremacy by promoting bigotry and violence against blacks and other minority groups.

The number of Klan chapters in the United States grew from 72 in 2014 to 190 in 2015, fueled by controversy over the Confederate battle flag, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks hate groups nationally. The center’s website identifies one Klan group in Maine, the Militant Knights Ku Klux Klan, but it provides no contact or membership information.

ANTI-CATHOLIC HISTORY

Maine’s small black, Jewish, Chinese and other immigrant communities were on the Klan’s list of undesirables in the 1920s.

An anonymous letter mailed to a black woman in Portland in 1922 accused her of serving “intoxicants” to soldiers, violating a Klan rule that “no (expletive) woman shall intertain white men.” The High Klokard of the KKK gave her six days “to pack and go” and warned that “Your DOOM is already sealed.” County officials told her to ignore the threat.

But it was the state’s large Irish Catholic and French-Canadian immigrant populations that were the KKK’s greater concern. Members and supporters denied harboring any intolerance, bigotry or religious prejudice, then sent letters like this to the Portland Press Herald:

“The real issue is Americanism against Romanism,” wrote Fred Moseley of Brunswick in April 1924. “Thinking, intelligent people do not believe it is for the best interests of the people to place Catholics in office. If a person is not 100 percent American, he is not an American. Let us elect good people to office,” rather than a politician who would sell “his soul to the devil to buy an election at the price of dishonor, bidding for the Roman vote.”

In the century leading up to the Klan’s surge, Maine’s mostly English Protestant founders had wrestled with each successive group of newcomers. Irish Catholics started arriving in great numbers in the 1830s, to work in the lumber industry in Bangor, cut stone in the Rockland area, dig canals and build mills in Lewiston, and work on Portland’s waterfront.

Many native-born Mainers viewed the Irish as destitute, brawling drunkards and papists who were fueling the Industrial Revolution that was forever changing their largely rural way of life. They lashed out in riot after riot, driving out Irish immigrants who had settled in Bangor in 1833, and burning a Catholic meeting house in Bath in 1854.

That same year, an anti-Catholic mob in Ellsworth blew up a chapel and tarred-and-feathered the Rev. John Bapst, a Jesuit priest who later founded a parish in Bangor and became the first president of Boston College. Catholic parishes in Portland and Newcastle posted guards to prevent similar attacks on their churches.

Tensions faded after the Civil War, when many young Irishmen volunteered, fought and, in some cases, died for the Union. “The way they conducted themselves in the war really changed public attitudes,” Shettleworth said.

French-Canadian Catholics followed in the late 1800s, filling factories and tenements in Biddeford, Saco, Lewiston, Augusta and Waterville. Language and culture differences complicated their integration into a society that was still mostly Protestant and inflamed conflicts with groups that came before.

“Each wave of immigration was met with opposition,” Shettleworth said. “They were attracted to the jobs available in major population centers, but there was definitely resistance by the local populations.”

CATHOLIC POPULATION GROWS

While Maine’s overall population increased steadily with each influx of immigrants, from 298,335 in 1820 to 768,014 in 1920, its Catholic population burgeoned to 153,225, or 20 percent of the population, according to U.S. Census and church sources. More significantly, among Mainers who identified themselves as regular churchgoers, 57.3 percent were Catholic, while the rest were divided among five Protestant sects, Edward Bonner Whitney wrote in “The Ku Klux Klan in Maine 1922-1928.”

Seizing opportunity from 1900 through the 1920s, Maine’s Catholic bishops increased the number of parishes in the state from 59 to 95 and the number of churches from 104 to 168, Whitney wrote. The number of Catholic schools grew from 33 to 68 and their overall student body increased from 8,236 in 1900 to 20,200 in 1926.

During the same period, 160 Protestant churches closed, fueling fears that the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic men’s group, was a militant gang eager to seize control of Maine politics, Whitney wrote. Maine also was hit harder than other states by the economic downturn that followed World War I, when factories and other businesses cut jobs, wages and work weeks, and farmers were selling out at a rate of 1,000 per year.

Moreover, many Mainers, like most Americans, were exhausted by a relatively short but horrible war and the painful investment that the United States had made overseas. Isolationist attitudes, coupled with Republicans’ distrust of the Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations, laid a foundation for the KKK to make a play for political power in Maine.

Mainers bought $104 million in war bonds in 19 months to support the war effort, 35,000 men and women from Maine enlisted in the war, and 1,000 men died, Shettleworth said.

“Even though we were only in the war a short time, its effect was felt everywhere,” Shettleworth said. “People wanted no further involvement with Europe. People wanted to have their country back.”

For many Protestants in Maine, immigrant Catholics became a primary focus of suspicion and blame, fostering a rebirth of nativism amid an immigration crackdown in the 1920s. The concern extended to Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, triggered by the “Red Scare” of communism following the Russian Revolution in 1917.

KLAN COMES TO MAINE

The first KKK members in Maine were three World War I veterans “who had pledged their devotion to the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan while they had been serving military duty in the South,” Lawrence Wayne Moores Jr. wrote in “The History of the Ku Klux Klan in Maine 1922-1931.”

Starting in late 1921, the veterans stirred interest among Bangor and Brewer residents, who wrote to KKK organizers in Georgia for information. The first initiation ceremony, conducted by Boston Klan members, took place in Bangor in late 1922, and a “klavern” or clubhouse with seating for 800 people was built on North Street in early 1924.

While some political leaders, ministers and community members welcomed the Klan to Maine, others spoke out against it. Gov. Percival Baxter, a Republican, issued a statement in 1922 calling the KKK “an insult and an affront to American citizens” that “must not and never will get a foothold in this state.” In 1923, Bowdoin College President Kenneth C.M. Sills was named to the National Vigilance Association, which fought the KKK throughout the country.

Still, the Klan spread quickly in Maine, with robe-clad Klansman appearing in parades in Milo, Brownville Junction and Lincoln. Portland developed as a center of influence, where KKK organizer Eugene Farnsworth of Boston delivered his “all-American” dogma to an initial audience of 500 Klansmen and guests in January 1923, according to Whitney.

A charismatic con man originally from Maine, Farnsworth soon became the King Kleagle in the state, heading several thousand men and women members in Portland alone. Despite protests from a 400-member veterans group and others, Mayor Carroll Chaplin decided that the Klan could meet at City Hall, as long as they didn’t wear robes and hoods.

“I know nothing against the Klan except what I have read in newspapers,” Chaplin told reporters. “Until trouble is caused, and until sedition or other unlawful doctrines are preached by any organization, I feel I cannot refuse it the use of city property of this sort.”

That spring, Dr. W.H. Whitham, a Portland physician who was a principal supporter of the Klan, purchased a sprawling Victorian estate on Forest Avenue for $76,500 to be the group’s clubhouse. A three-story, 6,600-seat meeting hall was added in February 1924 and began hosting a variety of family-oriented activities, including public dances and a massive circus.

The Klan was instrumental in promoting the passage of a new form of city government that included a city manager and an entirely at-large city council. The charter change eliminated district representatives and virtually ensured that no Roman Catholic or Jewish immigrants would win election. The city later resumed district representation.

“Portland has a dark history that involves the KKK,” said David Marshall, a former city councilor who has studied the city charter. “The negativity of that time doesn’t match the current progressive values of the city, but there is a lesson to be learned from it. There is a risk that government can be controlled by people with isolationist values and we need to do what we can to avoid going there again.”

THE KLAN’S DECLINE

The KKK’s growth and influence peaked in Maine with the election of Gov. Ralph Brewster of Portland, who denied being a member of the group but welcomed its support. Membership topped out at about 40,000 statewide, according to Whitney, though estimates range from 20,000 to 150,000 in a 1930 nationwide study by The Washington Post.

Financial and organizational scandals led to Farnsworth’s ouster in May 1924, and the new meeting hall at the Portland clubhouse burned to the ground in December of that year. Brewster was re-elected in 1926, but overt KKK support and political activity was waning as opposition to the group grew nationally amid the economic boom that briefly preceded the Great Depression.

By 1930, the Portland Sunday Telegram reported that there were about 225 Klan members across the state, though sympathizers likely still existed.

“The uncertainty and instability of the postwar era evolved into great prosperity,” Shettleworth said. “The country felt more secure and its focus moved onto other things.”

Shettleworth noted how Maine’s experiences in the 1920s inform current events, as is often the case when examining the past. He sees lessons to be learned and reason to have hope.

“It’s interesting to see how certain things in our history tend to repeat themselves,” Shettleworth said. “What we’re experiencing today might not be unique to our times. It has precedence. History can be a teacher for people who are currently trying to make some sense of what’s going on around us. We have worked through these issues before, we found answers and we moved forward.”

Kelley Bouchard can be contacted at 791-6328 or at:

kbouchard@pressherald.com

Twitter: KelleyBouchard

Send questions/comments to the editors.